In addition to our usual questions, there were a number of new measures of interest, some of them based on hypotheses generated by the academic literature, others based entirely on questions asked of us by furries online and at conventions. In the end, we asked a variety of questions covering demographics, felt stigma against the fandom, self-esteem, connection felt with one’s fursona species, fantasy involvement, personality (both fursona personality and non-fursona personality), ideas about why the fandom is male-dominated, fan entitlement, attitudes towards animal rights, pet ownership and healthy/unhealthy fandom activities.

In sum, we asked more than 300 questions. The data are currently being analyzed (and there are a near-infinite ways to potentially analyze the data), and so summarized/interesting data are presented below.

As always, if you have any questions or would like clarification of the data here, or would like to suggest an analysis/test a hypothesis, please contact us (see link on the sidebar).

Please note that all collected information is presented here in aggregate (summarzied) form, and there is absolutely NO identifying information in the data. We have no way of tracing responses back to the original participant (this is an anonymous survey). Additionally, any unique responses (e.g. species types selected by only one person) are not reported, to protect the anonymity of the participants.

Additionally, summary statistics and the output of different analyses are included in this presentation of the data (e.g. t-tests, ANOVAs, regression analyses, means). They are always in brackets, and are always summarized just prior to their presentation. It is not necessary to understand them, but are included for the sake of anyone with a knack for stats or who wants to know a little more about the technical side of the research.

Summary of questions:

Demographics

Q1: Where did the furries in your sample come from?

Q2: How old is the average furry?

Q3: How much of your sample was furry? Therian? Otherkin?

Q4: What is the ethnic breakdown of the furry fandom?

Q5: What is the sex breakdown of the furry fandom?

Q6: What is the gender breakdown of the furry fandom?

Q7: What is the sexual orientation of furries?

Q8: Are furries mostly single or in relationships?

Q9: What kind of education does the average furry have?

Furry Statistics

Q10: How “furry” is the average furry?

a. Identify with being a furry

b. Identify with other furries

c. Identify with their fursona species

d. Identify with the furry fandom

e. Importance of furry in defining me

Q11: How long has the average furry been a furry for?

Q12: Do furries/therians consider themselves human?

Q13: What have you learned about fursonas

a. How many fursonas does the average furry have?

b. Do furries use fursonas to decide who to interact with?

c. Do furries think fursona species says something important about a person?

d. Do fursona personalities differ from non-fursona personalities?

Animals

Q14: Are furries more likely to be vegetarians?

Q15: How do furries feel about animal rights?

Q16: Do furries own pets?

Furry Community

Q17: Do furries feel a sense of “entitlement” when it comes to artists?

Q18: How much do furries think the average person knows about their community?

Q19: How distinct is the furry fandom from related fandoms?

Q20: Furries and fantasy: Do furries have an active imagination?

Demographics

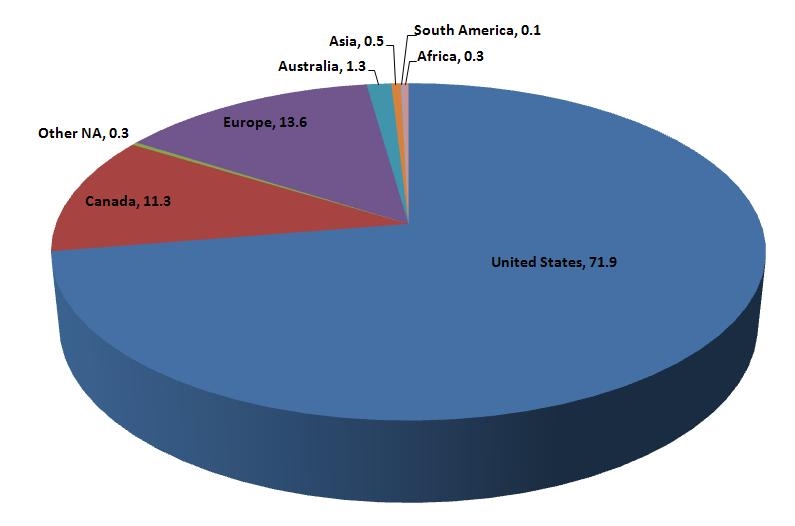

Q1: Where did the furries in your sample come from?

In this survey, approximately 70% of our sample (N = 776) came from online sources (e.g. Wikifur, local furry forums, Flayrah, Furry News Network, FurAffinity, etc…), while the remaining 30% (N=322) completed the survey at Furry Fiesta 2012.

The above figure, showing the percentage of the furry sample that came from various locations, illustrates another consistency with our previous research: the majority of furries in our study are from North America and Europe. That said, we consistently report furries from a number of countries all over the world, and would undoubtedly be better able to tap into many of these populations if, in future surveys, we were to use translated versions of our surveys and to access more regionally popular/relevant furry websites.

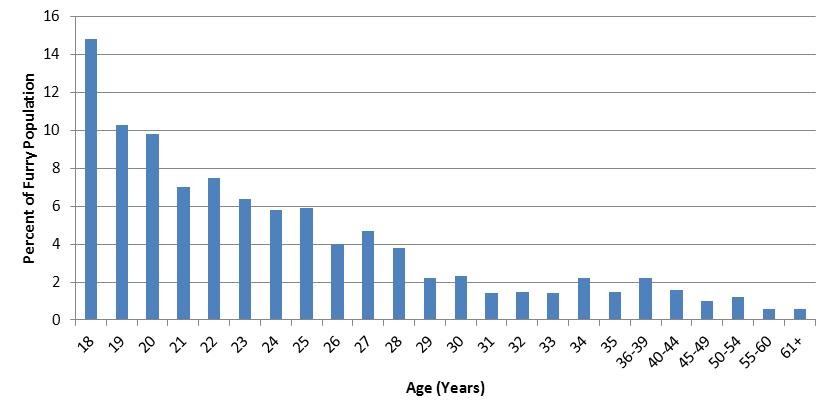

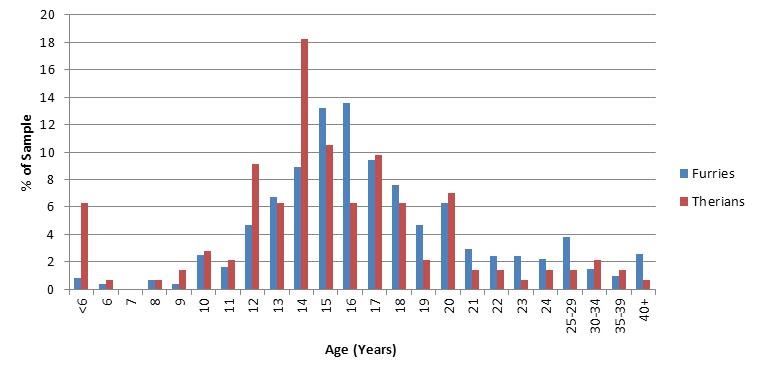

Q2: How old is the average furry?

As we have found in previous years, the age distribution of furries illustrates that the majority of furries are relatively young. While minors from the study had to be cut due to ethical restrictions, these data suggest that the fandom is comprised primarily of under-25 participants. That said, there is also evidence to suggest that there is a significant proportion of furries over the age of 25 (upwards of 30%), and with furries of all ages being present in the fandom, well into their 50s and 60s.

Q3: How much of your sample was is furry? Therian? Otherkin?

In total, 90.1% of our participants self-identified as furry, with another 9.9% identifying themselves as non-furry.

Beyond this, we also asked participants whether they identified themselves as therians and/or as otherkin. Our past research has suggested that while there are a remarkable number of similarities between furries, therians, and otherkin, there are differences which, for many, are particularly important and meaningful.

We allowed participants to use their own definition of what a therian and an otherkin was. For the purposes of our readers here, therianthropy, as best determined by our past research and based on interviews/discussions with therians, is the belief in a felt connection to one’s fursona – be it a spiritual connection, psychological connection, physical connection, or otherwise (a feeling of identifying with a particular species in one fashion or another). Regarding otherkin: empirically, there have been essentially no distinguishable differences between therians and otherkin, and the closest we’ve been able to approach regarding a “definition” of otherkin is that they represent therians whose connected species is one of fantasy/lore (e.g. dragons, mystical creatures). Of course, there is a tremendous amount of research to be done on the subject in future surveys, and these definitions are not intended to be “official” or “authoritative” in any way; they are merely meant to guide the uninformed reader as to what some have defined therians and otherkin as.

When asked if they considered themselves to be a therian, 14.5% of our participants said yes, 58.4% said no, and the remaining 27.1% said they did not know what a therian was. Of the people self-identifying as therians, 94.7% of them also identified as furries (suggesting that 5.3% of therians in our sample did not identify themselves as furry).

A similar analysis was conducted for otherkin, and found that 11.9% of our sample identified themselves as otherkin, while 65.0% did not, and another 23.2% said they did not know what an otherkin was. 89.6% of the otherkin in our sample identified themselves as furries.

Finally, 36.2% of therians also identified themselves as otherkin, and 5.0% of our total sample identified as a furry, therian, and otherkin.

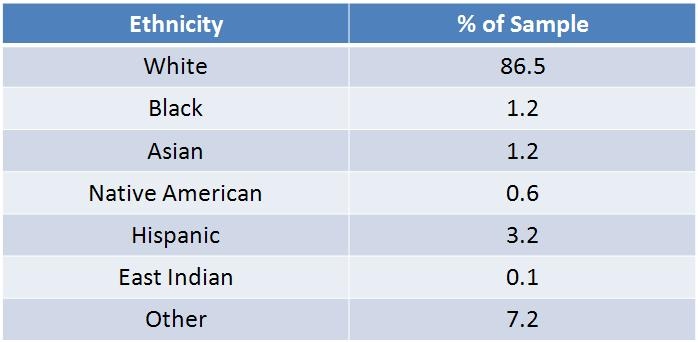

Q4: What is the ethnic breakdown of the furry fandom?

As the above figure (and past research on the fandom has shown), the furry fandom tends to be primarily, though certainly not entirely white. A number of other ethnic groups are represented in our sample, and it is likely that our research being conducted in western cultures contributes, at least in part, to these findings.

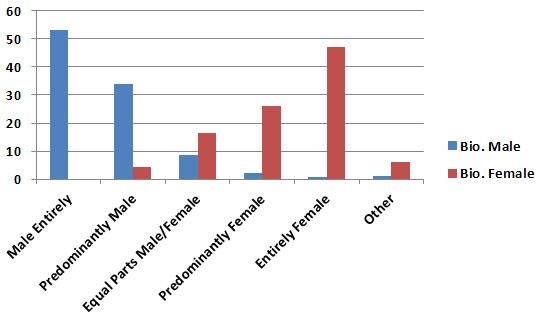

Q5: What is the sex breakdown of the furry fandom?

Participants in our survey were asked to identify their biological sex. Interestingly, while the fandom was still heavily male-dominated, with 76.8% of furry participants reporting being biologically male, it should be noted that this is down considerably from our average of about 85% from past surveys. While one data point is certainly not enough to suggest a trend, it may be an encouraging sign of the fandom becoming increasingly inviting for females, with 21.0% of furry participants reporting being biologically female. Finally, 2.2% of furries reported being either transgendered or “other”.

Q6: What is the gender breakdown of the furry fandom?

Recognizing that sex and gender are two completely different concepts, we also asked participants to identify, on a 5-point scale ranging from “Entirely male” to “Entirely Female” (with options for predominantly male/female and equal parts male/female), with the additional option to select “other”.

As you can see, an appreciation for the fluidity of gender as a construct suggests that for up to half the fandom there is at least some difference between biological sex and gender, with approximately half of the fandom identifying at least somewhat with traditionally masculine and feminine traits. Additionally, females are more likely than males to reject altogether the notion of gender being identifiable on a dimension ranging from “male” to “female”.

Finally, a t-test (a statistical test measuring whether two groups significantly differ on a variable) found that therians were statistically significantly more likely than non-therians to experience a gender identity that differed from their biological identity (Therians = 1.89, Non-therians = 1.78; t(182.181) = 3.06, p = .003). This has interesting implications, given our research team’s prior suggestion that in the same way a person can experience gender identity disorder (the persistent feeling of being born as the wrong biological sex), it may also be possible for a person to experience a sense of “being born in the wrong species”. This is, of course, far from evidence that the two are at all related, but it is interesting data nonetheless, which will no doubt be studied in our future research.

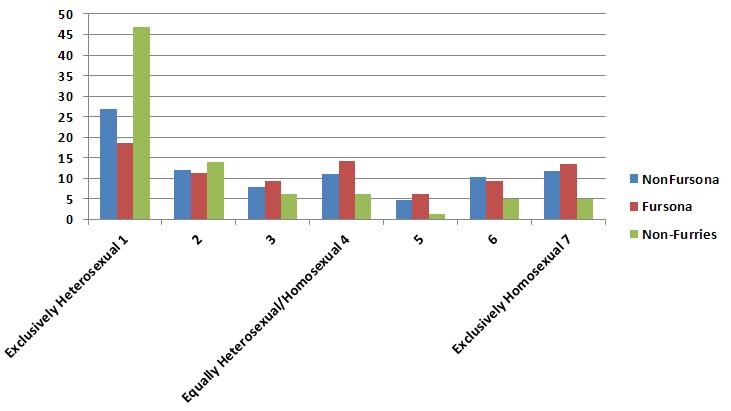

Q7: What is the sexual orientation of furries?

The above figure is fairly consistent with our past research on furry sexual orientation, suggesting that furries are approximately half as likely as non-furries to be exclusively heterosexual and are about twice as likely as non-furries to be exclusively homosexual or bisexual. Interestingly, another past finding was also replicated in this research, showing that a person’s fursona is more likely to be bisexual than they are (though the effect is not as pronounced here as it was in previous, larger samples). Additionally, our data suggested that, among furries, 8.1% reported being pansexual, while another 4.7% reported asexuality (with 11.5% of furries saying their fursonas were pansexual and 4.7% stating their fursonas were asexual).

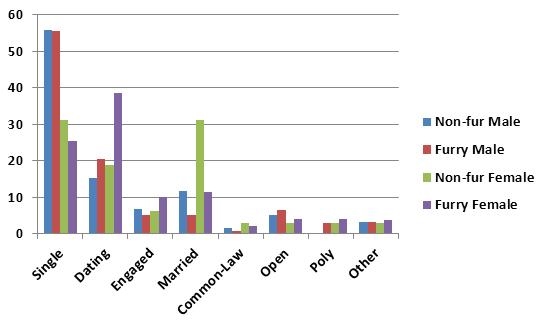

Q8: Are furries mostly single or in relationships?

As compared to non-furries in our sample, furries were slightly less likely to be single (48.7% vs. 45.7%), much more likely to be in a monogamous relationship (31.6% vs. 24.0%), were much less likely to be married, likely due to the age distribution of the fandom (6.1% vs. 16.3%) and were more likely to be in open or polyamorous relationships (9.4% vs. 5.7%).

Interestingly, breaking down the data a bit further, a previously-noted trend from past research yet again emerges: female furries tend to be particularly likely to be in a relationship, relative to male furries (or even non-furry females). Some of the researchers hypothesize that this may be due to female furries getting into the fandom in the first place by way of a significant other: given the previously-mentioned high proportion of males in the fandom, it may prove difficult for females to find a way to get into the fandom in the first place without an “in” such as being an artist or friend of a friend. Having a significant other provides a foot in the door for females to join the fandom where they may otherwise have had little opportunity (or have not felt welcome).

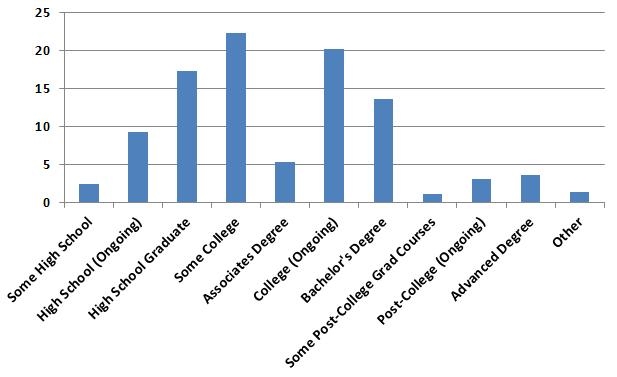

Q9: What kind of education does the average furry have?

As the figure above shows, 69.6% of furries report at least some college education (in progress or completed), with 26.8% reporting at least one completed degree. This data is representative of data obtained from our past research.

Furry Statistics

Q10: How “furry” is the average furry?

While it may seem easy to ask furries how much they feel like a part of the furry fandom, it only takes a little thinking on the subject (and talking to other furries about it) to realize that it can be a particularly difficult thing to measure. For example, if one were trying to determine which of two people is “more furry”, would they decide based on who identified more with the community? Or with the person who felt closer to their fursona? What about the person who identified most with the idea of “being furry”, regardless of how they felt about other furries or about their fursona?

To get at this multifaceted concept, we asked several questions of this type to the participants in our survey, allowing us to compare the results and see just how related (or unrelated) these concepts are for furries.

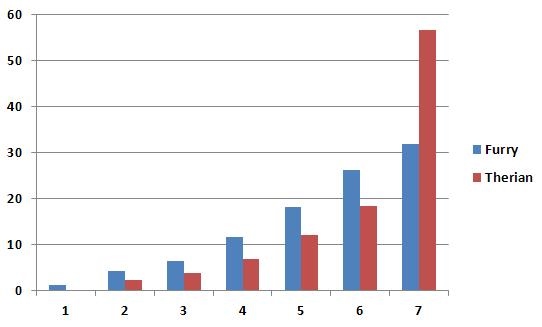

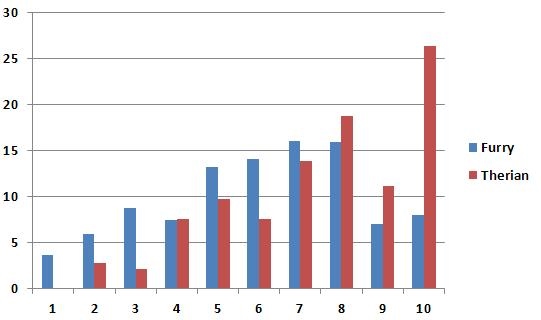

a. Identify with being a furry

We asked furries to indicate, on a 7-point scale, the extent to which they agreed with the statement “I strongly identify with being a furry” (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). As you can see, there was some variation in responding, but on average furries tended to report significant agreement with this statement.

A follow-up analysis suggests that therians, as a group, tend to identify with being a furry moreso than furries, as a group (Therians = 6.11, Furries = 5.48; t(230.972) = 4.82, p < .001). This is driven entirely by the sheer number of therians selecting “7” on this scale. This also suggests that there is more variation among furries (SD Furries= 1.50 vs. SD Therians = 1.29; Levene’s F = 7.76, p = .005) regarding the extent to which they identify with being a furry (i.e. there are both “casual” and “lifestyle” furries, whereas such a distinction may not be made for therians).

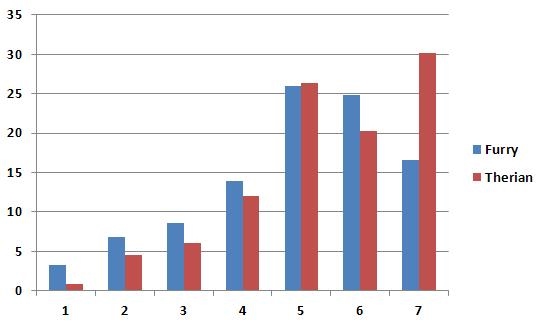

b. Identify with other furries

Participants were also asked to indicate, on the same 1-7 scale as above, the extent to which they identified with other furries. As you can see here, while there was a fairly good spread of responses, most furries indicated feeling relatively close to other furries (though it should be noted that the shape of this curve differs considerably from the curve for identification with being a furry). In particular, it seems that furs tend to identify with being a furry (M = 5.48) more than they identify with other furries (M = 4.93; F(1,846) = 114.905, p < .001).

It is also the case that, in a manner similar to identification with being a furry, therians reported greater identification with other furries (M = 5.40) than furries did (M = 4.93; t(643) = 3.058, p = .002).

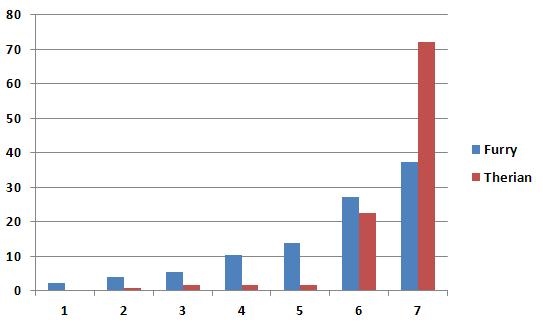

c. Identify with their fursona species

On the same 1-7 scale as above, participants were asked to indicate their agreement with the statement that they identified strongly with their fursona species. In a manner similar to reported identification with being a furry, furries tended to report feeling a relatively strong sense of identification with their fursona species. The similarity of responses to these two items (a relatively strong correlation, r = .60, p < .001) suggests that for many furries these two concepts go hand-in-hand: identifying as a furry also tends to mean identifying with one’s fursona species.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, for therians, which are often defined as people who feel a connection to a non-human species, responses show overwhelming support for identification with one’s fursona species. Therians reported significantly greater identification with their fursona species than furries (Furries = 5.60, Therians = 6.60; t(398.046) = 10.03, p < .001).

A final point of interest: while the correlation between identification with being a furry and identification with one’s fursona species is .60 for furries, it is only about half that size, .32 (p < .001) for therians. This suggests that for furries, identification with one’s fursona species is more closely tied to their furry identity than for therians. This may be because therians make a distinction between “identifying as a therian” and “identifying as a furry” (e.g. their identification with their fursona species makes them a therian, but their interest in furry artwork or their participation in the furry community, for example, is what makes them “furry”).

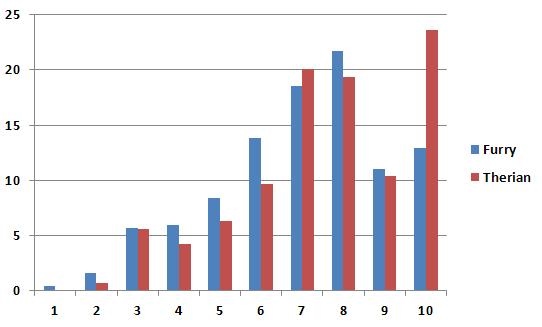

d. Identify with the furry fandom

On a different set of questions, participants were asked to indicate, on a 10-point scale, the extent to which they considered themselves a part of the furry fandom (from “extremely weakly” to “extremely strongly”). While this question may appear, on the surface, similar to the questions about “identifying as a furry” and “identifying with other furs”, it should be noted that the correlations were not perfect (r = .59 and r = .51, respectively, both p <.001). This suggests that, while related, furries do make a distinction between what it means to identify as a furry, to identify with other furries, and to be a part of the furry fandom.

Data again showed that therians, on average, reported feeling more strongly like a part of the furry fandom than furries did (Therians = 7.51, Furries = 7.01; t(699) = 2.58, p = .01), owing largely to a large proportion of therians maxing out the scale and reporting extremely strongly that they were a part of the furry fandom.

e. Importance of furry in defining me

Finally, participants were asked to indicate, on the same 1-10 scale as above, the extent to which “being furry” was important in defining who they were. This construct was found to be highly related to the concept of identifying with being a furry (r = .65, p <.001), suggesting that for furries these were similar questions.

As with all of the items in this section, therians were more likely than furries to state that furry was an important part of defining who they were (Therians = 7.48, Furries = 6.05; t(702) = 6.46, p < .001). This may reflect another important distinction between furries and therians: for furries, given the previously suggested notion that there is a wide range of possible levels of involvement in the fandom, furries may be more likely to refer to furry as a fan activity or hobby, whereas therians may be more likely to see furry as something that defines them, not simply a hobby.

Q10 Summary

The data in this section tell us just how complicated the story of “what it means to be a furry” is. A seemingly simple question asking participants to indicate the depth/extent of their interest and involvement in the furry fandom has proven itself to be multifaceted and nuanced, showing that depending on which question you ask, you may get very different responses. Different furries define their involvement in the furry fandom in different ways: they may identify with being a furry, with a fursona species, with the community, with a specific subgroup of furries, or with any combination of these.

It is also worth noting that across all of the measures, therians reported greater identification with various elements of the furry fandom, in particular those associated with their fursona species. Future research may help us to tease apart the reasoning for this difference, including a test of our hypothesis that it has to do with a greater range of involvement among furries than is the case among therians.

Q11: How long has the average furry been a furry for?

Participants were asked to indicate their age and then to indicate several age-related furry questions: how many years they had been a furry for, the age in which they first realized they were a furry, and the age in which they became a part of the furry community.

Taking the “number of years you’ve been a furry” value and dividing it by participants’ current age, we were able to get a measure of the percentage of one’s life for which they considered themselves a furry. On average, furries reported having been a furry for 29.9% of their life, while therians reported having been a furry for 34.1% of their life on average, statistically significantly longer than furries (t(189.862) = 2.09, p = .038). The average furry reported having been a furry for 7.65 years, while the average therian reported having been a furry for 8.67 years.

The average furry stated that they first considered themselves a furry at the age of 17.1 years, fully a year and a half older than the average therian, who reported first considering themselves a therian at the age of 15.6 years (significantly younger than furries, t(693) = 3.48, p = .001). This is in line with anecdotal reports from many therians who have reported strong identification with/as animals from a very young age. The age distribution is displayed below.

Finally, the average furry participant reported first becoming a part of the furry community at the age of 19.2, about a year later than the average therian participant who became a part of the community at the age of 18.3, a statistically significant difference (t(612) = 2.23, p = .026).

In sum, there is evidence to support many therians’ claim that “furry” feelings were present earlier for them than for furries. Additionally, evidence here replicates past findings that there exists a nearly two year gap between the time a furry decides that they are a furry and their actual participation in the furry community. Future longitudinal studies may help us to explore the difficulties furries may experience during this time, including possibly struggling to find a group with which to identify and validation of the interesting feelings/interests/identity they have.

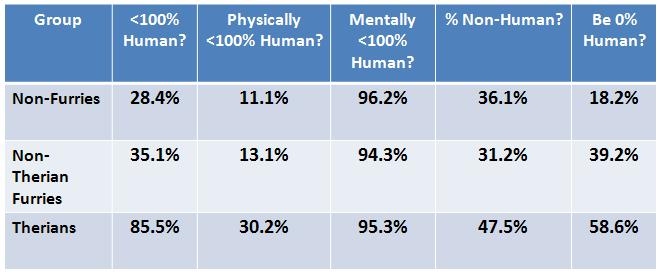

Q12: Do furries/therians consider themselves human?

*** Note that in the above figure, “Physically <100% Human”, “Mentally <100% Human”, and “% Non-Human” responses are displayed ONLY for furries who responded that they felt <100% human. ***

Perhaps one of the most commonly asked questions about furries by both furries and non-furries alike: “do they actually think they’re animals?” Attempting to replicate and build upon previous years’ work, we asked a number of questions: whether participants felt less than 100% human, whether they felt physically or mentally less than 100% human (if they felt <100% human at all), what percent “non-human” they felt if they felt <100% non-human, and whether they would be 0% human if they had the choice.

The obtained results speak strongly about the primary difference, empirically, between therians and non-therian furries: a genuine belief in a connection to animals that may include feelings of being not entirely human (or, at very least, of having aspects of one’s fursona within oneself). Comparing non-therian furries to non-furries, there is only a slight difference in their belief that they are not entirely human. The biggest difference between furries and non-furries arises in their stated willingness to be 0% human if they could, with furries being about twice as likely as non-furries to report wanting to be 0% human. Therians, on the other hand, report significantly stronger feelings than either non-furries or furries that they are less than 100% human. Nearly everyone who felt less than 100% human reported that it was primarily feeling mentally less than 100% human, though therians were 2-3 times more likely to state, in addition, that they felt physically less than 100% human. Finally, therians reported feeling more “non-human” and a greater desire to be 0% human than either non-furries or non-therian furries.

In sum, it is not accurate to characterize furries as “people who do not think they are human” – in fact, only about 1 in 3 furries endorses this belief (which is not much higher than our non-furry control group). It would be much more accurate to describe therians, as a group, as people who felt not entirely human. Additionally, it should be noted that furries are not even accurately defined as people who, while not feeling inhuman, wish they could be: only about 40% of furries would be 0% human if they could: the majority of furries have little to no interest in the idea of being actually being completely non-human.

Q13: What have you learned about fursonas?

One of the most visible parts of the furry fandom is the fursona: they are ubiquitous in the furry fandom, and nearly every furry has at least one fursona. Given their prevalence, it is surprising how little is actually known about the nature of furries and their fursonas. Our past research has helped to solidify things which many furries suspected about fursonas (e.g. what the most popular species were), but numerous questions remain on this interesting topic. Below we will discuss data that speaks to these questions.

a. How many fursonas does the average furry have?

Participants were asked to indicate the number of fursonas they have had over the course of their life and the number of different species they have identified with (as fursonas) in their life.

Non-therian furries reported having an average of 2.75 fursonas over the course of their life, a number that, while smaller than therians’ reported average of 3.20 fursonas, was not quite statistically significantly different (t(176.495) = 1.92, p = .057). Furries also reported identifying with fewer species (M = 3.09) than therians (M = 3.64), a difference which was statistically significant (t(173.686) = 2.12, p = .035).

Thus, it seems to be the case that therians report having more fursonas and identifying with a greater number of species over the course of their lives than furries. A number of suggestions for additional questions on the subject have been offered to us by furries at Furry Fiesta 2012 and in the weeks following, to help elaborate on this subject (including questions about multiple fursonas held simultaneously and length of time people had various fursonas). These will more than likely make it onto future surveys as we investigate the nature of fursonas and their importance to furries and therians.

b. Do furries use fursonas to decide who to interact with?

Given that many conventions we’ve attended have special meet-up sessions based on species (e.g. wolf or feline meet-ups), and given observations by the researchers about things overheard at conventions on the subject of interacting with furs of different species (e.g. “ugh, he’s a fox, you know what they’re like”), we wondered whether furries actually considered fursona species to be diagnostic enough a piece of information about a person to use in a decision about whether to interact with that person.

We asked furries to indicate, on a 10-point scale, their agreement or disagreement with the statement that a person’s fursona species could influence how well you would expect to get along with that person (1 – disagree, 10 – agree).

Obtained data suggested that furries, on average, disagreed with this statement, with an average score of only 3.15. Therians, who report identifying more deeply with their fursonas/ chosen species, may be expected to consider this a more useful piece of information to know about someone. However, the data suggest otherwise, with therians having an average score of only 3.31, not statistically different from furries’ scores (t(668) = .682, p = .496).

Thus, it seems to be the case that neither furries nor therians seem to use a person’s fursona choice as a way of gauging whether or not they would get along with them.

c. Do furries think fursona species says something important about a person?

Given the obtained findings from the previous section, one might anticipate that furries did not think a person’s fursona choice was particularly useful in telling them something about that person (at least insofar as deciding whether or not to interact with that person).

However, we asked furries to indicate their agreement or disagreement, on the same 10-point scale as above, with the statement “a person’s fursona species choice tells you a lot about that person”.

Interestingly, furries were much more likely to agree with this statement than with the previous one (F(1,886) = 852.222, p < .001), though their average score of 5.72 suggests that there was only moderate agreement with the statement. Therians, on the other hand, were far more likely to agree that a person’s fursona choice told you something important about a person, with an average score of 6.81, statistically significantly higher than furries (t(668) = 3.34, p = .001).

In sum, while neither furries nor therians would think to use a person’s fursona choice as a means of predicting whether or not they would get along with that person, they do nonetheless see at least some value in a person’s fursona choice as providing information about that person. Therians were especially likely to endorse this belief.

d. Do fursona personalities differ from non-fursona personalities?

So, furries and therians at least somewhat agree that a person’s fursona choice can tell you something about that person. But what about fursonas in general – are they closely tied to a person’s actual personality? Are there predictable differences between furries and their fursonas?

This question was evaluated using a well-validated 10-item personality measure from the psychological literature. It looks at five of the most well-studied, validated personality traits in the literature: extraversion (the extent to which a person is outgoing/ energized by social activities), agreeableness (the extent to which a person seeks harmonious, non-confrontational interactions), conscientiousness (mindfulness, organization, planning), emotional stability (resistance to emotional outbursts and neurotic/pathological thoughts), and openness to experience (the extent to which a person favors and embraces new experiences).

Each participant rated both themselves and (if it applied) their fursonas on ten personality traits which represented various aspects of these five traits. The data are displayed below, along with previously-established norms on each of these five traits (based on the responses of thousands of participants from other research).

Of particular interest is a comparison of the “non-fursona” and “fursona” columns. For all five traits, furries rated themselves significantly different from their fursona: their fursonas were more extraverted, more agreeable, more conscientious, more emotionally stable, and less open to experience than they were (all p< .001). It remains for future research to determine whether having a person think about themselves in their fursona/ referring to them by their fursona/ having them fill out the survey while in their fursuit would actually cause them to identify themselves as being more like their fursona on these personality traits (e.g. whether their fursona actually changes their personality).

It is also worth noting that, for the most part, furries did not differ statistically significantly from the non-furries on any traits except for extraversion: furries reported being less extraverted (more introverted) than non-furries (p < .05). This difference, however, is completely removed (and in the reverse direction, in fact) when it comes to furries’ fursonas, which may make furries more outgoing (this remains to be seen in future research).

Finally: it should be noted that, with the exception of openness to experience, furries’ fursonas seem to have a “normalizing” effect, in that they are closer to established personality trait norms than furries themselves. This has a number of interesting implications, including the possibility of some furries using a fursona as a means of ameliorating/changing an aspect of their personality to be more “normal” / less deviant, rather ironically, given the idiosyncratic and oftentimes decidedly “not normal” nature of the furry fandom.

Animals

Q14: Are furries more likely to be vegetarians?

When asked if they were currently a vegetarian, 3% of furries and 6% of therians responded “yes”. When asked if they had ever been a vegetarian, 14% of furries and 10% of therians responded “yes”. These responses did not differ significantly from one another, nor did they differ significantly from the responses of non-furries.

Q15: How do furries feel about animal rights?

We asked participants about animal rights in a number of different ways. One way was to ask them, directly, whether or not they a) supported animal rights, and b) considered themselves to be an animal rights activist. 83% of furries reported that they supported animal rights, and 7% said that they considered themselves to be an animal rights activist, numbers which did not differ significantly from non-furries’ responses. Therians, on the other hand, were statistically significantly more likely to both support animal rights (Therians: 94%; t(139.305) = 2.52, p = .013) and to self-identify as an animal rights activist (Therians: 19%; t(65.150) = 2.15, p = .035).

We then asked participants about their agreement/disagreement (on a 1-5 scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) with 28 different animal rights issues.

In particular, furries felt felt strong agreement with items showing concern about displacing animals for land use, the use of animals in laboratory research, pain and suffering in animals, wearing of animal fur, and cosmetics testing on animals. They tended to disagree or be relatively unbothered by eating of animals or animal products.

We created a composite of the 28 items to create an overall scale of animal rights activism. Therians were significantly higher in their agreement with concerns over animal rights activism than furries (Therians = 2.60, Furries = 2.36, t(200) = 2.67, p = .008). This is, perhaps, unsurprising, given that therians are more likely to identify with animals and could thus be expected to be more sympathetic to animal rights issues.

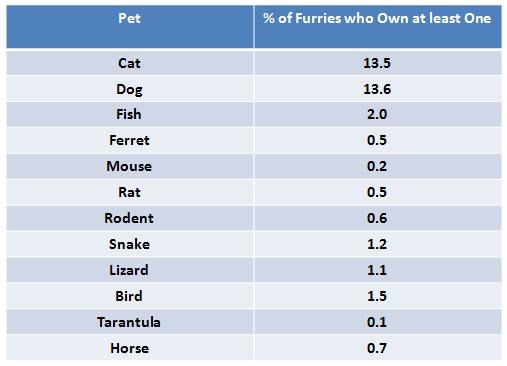

Q16: Do furries own pets?

We asked participants several questions about pet ownership, including whether they had ever owned a pet, currently owned a pet, and the number and type of pets currently owned.

98% of furries and therians reported that they had owned a pet at one point in their lives. 68% of furries and 78% of therians reported that they currently owned a pet (a number which did not significantly differ).

Furries reported owning an average of 2.72 pets, while therians reported owning an average of 3.65 pets.

Below is a table summarizing the popularity of the most popular pets for furries.

Furry Community

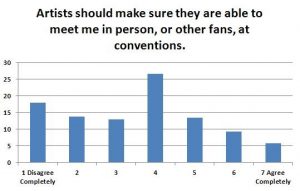

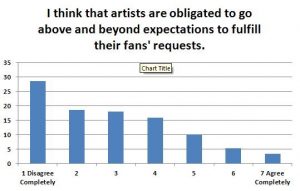

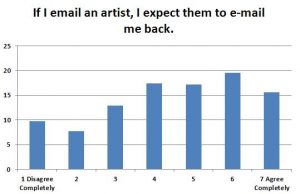

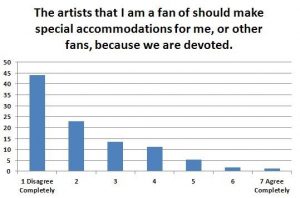

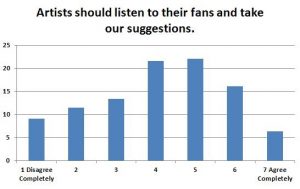

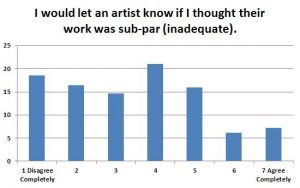

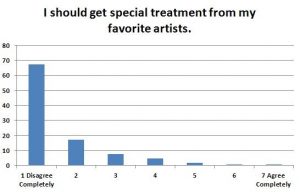

Q17: Do furries feel a sense of “entitlement” when it comes to artists?

The furry fandom is unique from other fandoms for many reasons. One of the most prominent reasons, however, is its largely independent and decentralized nature: in comparison to other fandoms (e.g. science fiction, fantasy) where content is driven primarily by a few large, professional sources (e.g. television shows, publishing companies), the furry fandom’s content is almost entirely user-generated. Nearly every furry has a unique fursona, many furries purchase art from or are themselves independent artists, and while some shows/ large studios are the source of some of the fandom’s content (e.g. Pokemon, My Little Ponies, Disney movies), they certainly do not comprise the bulk of the fandom’s content.

As a result of this independent artist/ fan-driven content culture, we wondered what the effect would be on the relationship between content creators (artists) and furries. For example, in the sci-fi fandom, it is much more difficult for fans to insist what shows like Dr. Who, Star Trek or Battlestar Galactica “ought to be”, given the relatively little influence they have over the professional studios that produce the shows. In contrast, for small, independent artists, who may oftentimes be commissioned by furries themselves to produce specific pieces of art, there may be a greater sense of entitlement on the part of furries. We evaluated this with several questions, the data for which are illustrated in the figures that follow.

For each statement, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

In a follow-up analysis, we looked at the reliability of these seven items (essentially, testing whether they were all measuring the same attitude of entitlement, or whether a person’s score on 1 of the items could reasonably predict their scores on the other times. In other words: if a person scores high on one of these items, are they more likely to score high on all of them?) The items were fairly reliable, and thus we conclude are a reasonable measure of attitudes of entitlement among fans.

It should also be noted that not all of the activities are endorsed equally by furries. For example, the average agreement score was 4.46 for the item about expecting artists to e-mail you back, as compared to an average agreement of 1.62 for the item about getting special treatment from one’s favorite artists. This suggests that certain behaviours, such as expecting special treatment or expecting artists to fulfill fan requests, are particularly diagnostic/ indicative of attitudes of entitlement, moreso than others (e.g. expecting an e-mail back or agreeing that artists should listen to fan suggestions, which may be less reflective of entitlement).

For future reference, it would be interesting to compare felt entitlement among furries as compared to other fandoms, to determine whether or not furries have greater, equal, or less sense of entitlement when it comes to the content creators in the fandom. We would also be especially interested to hear what artists and other content creators within the fandom have to say about these results (are they surprising? Can you think of other questions you’d like to ask? Is there something you want to dispute, or do you have a hypothesis about furry fans as compared to other fans?).

Q18: How much do furries think the average person knows about their community?

To start, data collected in this survey suggest that furries, on average, have a significantly higher rating of furries (M = 73.1/100) than non-furries do (M = 65.1/100; t(939) = 3.55, p <.001). That said, it should be pointed out that on a 0-100 scale, with 100 indicating extremely positive feelings, the average non-furry rating of furries of 65.1 certainly isn’t negative (though it could also be argued that our control group, taken from people attending a furry convention or who were recruited through furry websites, are more likely to have a positive bias toward furries than the general population). In future studies we hope to have other control groups to compare these values to and get a better picture of the attitudes society has toward furries.

Participants were also asked to indicate their agreement with items stating that it was socially acceptable to be a furry, that non-furries were prejudiced toward furries, and that they were treated worse when people discovered that they were a furry. For all three of these statements, there was greater agreement with the item the more a person was “into the fandom” (a composite of the five items from Question 10). Put another way, the “more furry” a participant was, the more socially acceptable they said it was to be a furry (F(1,894) = 33.94, p < .001, B = .19), the more they felt non-furries were prejudiced against furries (F(1,894) = 7.83, p = .005, B = .093) and the more they agreed that they were treated worse when people learned that they were a furry (F(1,874) = 7.08, p = .008, B = .089).

Finally, participants indicated their agreement (1 – strongly disagree, 7 – strongly agree) with two statements about fandoms. One statement indicated that “everyone in America knows what furries are”. The other indicated that “everyone in America knows what anime is”. Data analysis showed that participants felt that the average American was much more likely to know what anime was (M = 4.10) than what furries were (M = 2.42; F(1,814) = 854.01, p <.001).

The above data say some interesting things about furries and their perception of how the world sees them. On the one hand, evidence suggests that there is a community of non-furries who are nonetheless supportive of furries (whether or not these attitudes extend beyond non-furries who know furries is another question). On the other hand, furries feel a tremendous amount of stigma from world around them, though moreso from non-furries (M = 4.73) than from anime fans (M = 3.85; F(1,885) = 62.05, p <.001), perhaps because of the perception that anime fans are similarly stigmatized by society. This is interesting, because furries report feeling this stigma despite the fact that many of them simultaneously report the perception that most of America has no idea what furries are. This may because furries feel stigmatized as an individual (e.g. as being an individual who, say, runs around in a fursuit or has furry artwork) partly because they feel that society doesn’t recognize that they are not an “isolated case”, but that there is, in fact, a vibrant and thriving fandom. Further research into perceptions of prejudice toward furries and perceived knowledge the rest of the world has about the fandom will help to address some of the questions raised here.

Q19: How distinct is the furry fandom from related fandoms?

An interesting aspect of the furry fandom is its independence as a fandom despite a tremendous degree of overlap with similar or related fandoms or groups (e.g. Disney, Anime, Cartoons, Bronies, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Therians, Otherkin, Gamers, Ravers, just to name a few). This led us to question the extent to which the furry fandom is perceived as being unique and distinct from a related/similar fandom: anime.

We asked participants to indicate, on a 7-point scale, whether or not they agreed that furries were a distinct and unique group when compared to anime fans. As you can see from the figure above (showing the percent of respondents who chose each level of agreement), furries strongly felt that their fandom was distinct from that of anime. In a further analysis, we compared furries and non-furries in their judgments of the perceived distinctiveness of the furry fandom from the anime fandom. Furries were statistically significantly more likely (M = 5.19) than non-furries (M = 4.75) to state that the furry fandom was distinct from anime (t(891) = 2.20, p = .028), while a follow-up analysis showed that the “more furry” a person was, the more strongly they felt that the furry fandom was distinct from the anime fandom (F(1,895) = 101.63, p <.001, B = .20), an effect which only got stronger after statistically controlling for whether participants themselves identified as an anime fan (it was the case that identifying as an anime fan actually decreased the perceived distinctness of the furry fandom, F(1,892) = 19.90, p <.001, B = -.15).

Another potential way to study distinctness of the furry fandom is to look at a trait referred to as “essentialism” – the belief that a group is based on some naturally-occurring, physical, tangible feature (examples of groups commonly perceived to be “essential” include gender and ethnicity, while examples of “non-essential” groups may be things like “a band class” or “the group of people standing in line at the bank” – groups with nothing inherently “groupy” about them except for superficial or transitory features). Included in the survey was an “essentialist” scale, measuring furries’ beliefs that furry, as a group, was something essential: something hard-wired, biologically based, or physically “real”. An analysis found that the more essential furry was considered as a group, the more distinct it was from anime, as a fandom (F(1,890) = 53.88, p < .001, B = .24).

In sum, it seems to be that the more closely attached one is to the furry fandom, the more distinct it is seen as being from other fandoms. This makes sense, from a psychological point of view: the groups we belong to serve a number of functions for us, one of which is to provide a source of identity for us. We like to have a clear sense of identity. The more our group is seen to blur with other groups (especially if those groups disagree with our perception of ourselves or our attitudes), and the less clear our groups’ boundaries seem, the more threatening this is to our sense of identity – who we are as defined by what group we belong to. Given that another analysis found that beliefs about the essentialism of furries as a group are significantly related to the extent to which a person identifies as a furry, it may be the case that believing the group to be essential is just one of many ways furries defend their definition of what “furry” is from being encroached upon by other, related groups.

In future studies, we hope to look at other groups that may threaten furry identity, including the controversial “brony” fandom, to see whether negative attitudes toward these fandoms are predicted by identifying with the furry fandom.

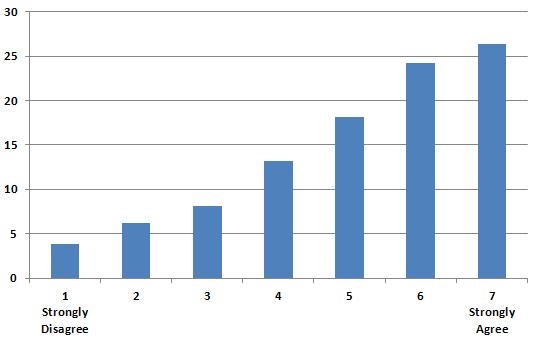

Q20: Furries and fantasy: Do furries have an active imagination?

Recently, one of the researchers has become particularly interested in the concept of fantasy and its potential function in the everyday lives of people. As an initial investigation into this, five different scales of fantasy were included in some or all versions of the survey. These scales looked at different aspects of “fantasy” as a concept, ranging from belief in supernatural / magical thinking (e.g. belief in premonitions about future events), ability to perspective-take and empathize (e.g. feel the pain of a character in a story), childhood (and current) experiences of fantasy behaviour and thoughts (e.g. having an imaginary friend as a child, having vivid daydreams), and a scale of fantasy activity as it pertains to the furry fandom (e.g. spending time thinking about furries, treating furry as a hobby/recreational activity).

Across all five measures a common trend surfaced: the more “furry” a person was (based on a composite of the five items from Question 10), the more they engaged in fantasy. Specifically, being “more furry” was related to greater engagement in magical thinking (F(1,317) = 18.05, p < .001, B = .23), more childhood (and current) fantasy experiences (F(1,317) = 22.58, p < .001, B = .26), greater perspective-taking and empathy (F(1,314) = 12.37, p = .001, B = .20) and more engagement in furry-related fantasy activity (F(1,923) = 563.14, p <.001, B = .62).

This is, of course, only an initial investigation into the subject, and the researchers are hoping to expand this research in a number of different directions in upcoming studies, including looking at different kinds of fantasies, the implications of this fantasy for the well-being of furries, and investigating how specific this fantasy engagement is for furries (e.g. is it a general tendency to fantasize about everything, or specifically furry things?).

Recent Comments