In July, the IARP attended Furry Fiesta for its sixth consecutive year (though Dr. Gerbasi and her colleagues have been doing research at Anthrocon before the IARP’s inception for several years more!) Anthrocon has always been the flagship of our team’s research, representing the biggest sample of convention-going furries we’ve got. As such, we spend a good portion of every year planning for our Anthrocon study, deciding which of the hundreds of questions we want to ask to such a large sample of the furry fandom. One of the difficulties of this task is paring down the number of questions we have from several hundred to a manageable 6-8 page survey. We managed to do so, balancing questions that were either very likely to be fruitful or which were very interesting to us and to furries. In striking this balance, we ended up doing three separate projects: our standard Anthrocon survey, a second, “artist-only” survey, and a post-convention follow-up survey.

This write-up represents a brief summary of the data we collected at Anthrocon 2015. As with all of the IARP’s write-ups, we endeavor to find a balance somewhere in the middle ground between writing up a small, overly simplistic point-form list of conclusions and flooding the reader with hundreds of pages of statistics. While there are certainly many more findings than are presented here, the present results were chosen because they are the most interesting to furries, have the most potential to lead to future research, or because they were the most surprising to us.

As always, if you have questions, concerns, or criticisms about the presented findings, or would like us to run an analysis to satisfy your own curiosity, please e-mail Dr. Courtney “Nuka” Plante at courtney.plante@furscience.com.

Methods: What did you actually do?

The data presented here represent a compilation of three separate studies that were conducted at Anthrocon or in the days following Anthrocon via online survey. In all studies, all participants were over the age of 18, as required by our ethics review board, and all participants’ information was contributed anonymously and confidentially.

The first study presented was a study of artists in the Anthrocon Dealer’s Den. It served as a follow-up to our Furry Fiesta 2015 artist survey, and sought to study a much larger, more representative sample of artists and writers in the fandom. Moreover, many more questions were added to the survey, using the feedback we attained from our Furry Fiesta 2015 artist survey. Questions on this short, two-page survey (it was kept short in the interest of not disrupting the workflow of busy artists in the Dealer’s Den) included demographic questions, questions about their art content / career, their attitudes toward fans and other artists, and questions prompting artists to discuss some of the common problems they encounter in the fandom. In total, of 150 surveys passed out to nearly every artist in the Dealer’s Den, 69 were returned to us. This represents a fairly good-sized sample of artists in the Dealer’s Den, though it is worth mentioning that this sample is unlikely to represent all artists in the fandom (e.g., online artists, new artists, older artists who no longer attend conventions, etc…)

The second study was the IARP’s annual Anthrocon survey, an 8-page survey handed out to nearly 2,000 furries attending Anthrocon. More than half of the surveys were handed out by the researchers to participants on the Thursday before the con, while they were standing in line waiting to register for the convention. The rest of the surveys were distributed by the researchers at their table in the Dealer’s Den throughout the course of the convention. Participants completed the survey in exchange for a ribbon for their convention badge, a small vending machine prize, and a donation to the convention charity. In total, 992 surveys were returned to us, of which 979 were useable (e.g., were not completed by minors, handed in blank, etc…) The survey was broad in scope, and included questions assessing general demographics, fantasy engagement, well-being, belongingness in the fandom, definitions of terms, fursona, species stereotypes, self-consciousness, and more.

The final study was intended to be a study following up on our general Anthrocon study. At the end of the Anthrocon survey, participants had the option of providing us with their e-mail address and a self-generated unique code. If they chose to do this, we e-mailed them, 3 or 7 days after the convention, with the link to an optional online survey. This survey included many of the same items from the general survey, as well as several additional items. In essence, the goal of this survey was to assess whether participant answers would change from the time they were at Anthrocon to the time they returned home and settled back into day-to-day life. A significant motivation for this study was prompted by furries’ discussion of a phenomenon they called “post-con depression” in many of our past focus groups: a felt “slump” or “down period” in the days and weeks following a furry convention. This study aimed to see if this phenomenon existed and, if so, whether it could be observed and measured using existing psychological instruments. In total, 154 participants completed the post-convention follow-up survey (83 completed the survey approximately 3 days afterward, 71 completed the survey approximately 1 week afterward).

Results: Get to the Data!

The results of our findings are presented with the aim of making them as accessible as possible to everyone reading, presented as a series of question-and-answer sections. To improve accessibility, we display two forms of our results: one geared toward an audience with little to no statistical background, who want a simple, concise answer to the research question, and a second targeted toward readers who are more stats-savvy, which include the results of t-tests, ANOVAs, and multiple regression analyses conducted using the statistical program SPSS.

Part 1: Artists in the Fandom

1. Does the sex/gender composition of artists in the furry fandom differ from the rest of the fandom?

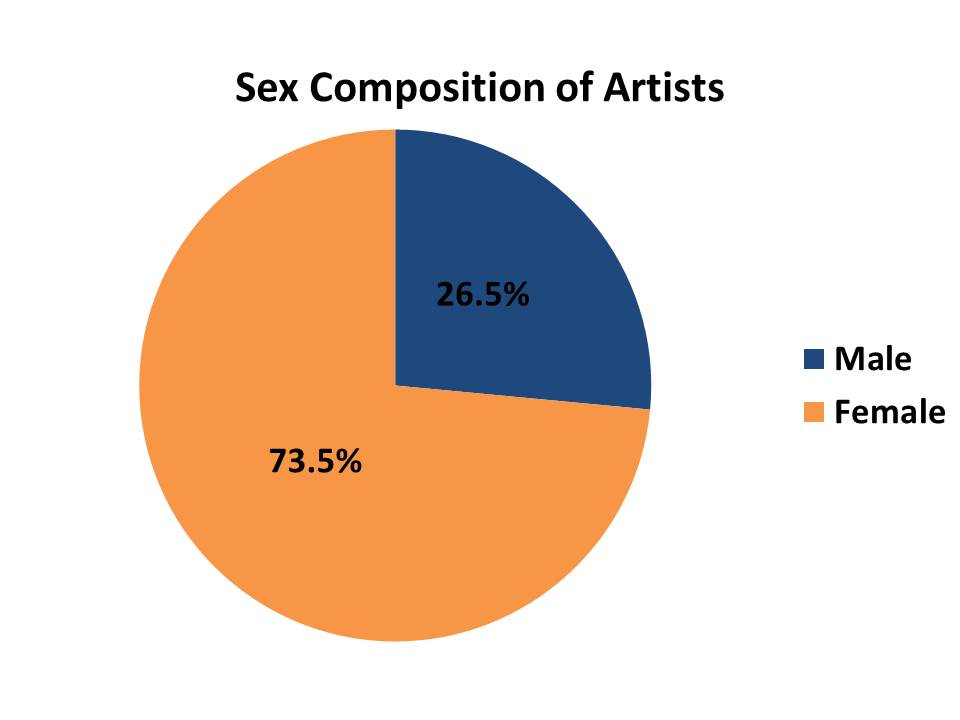

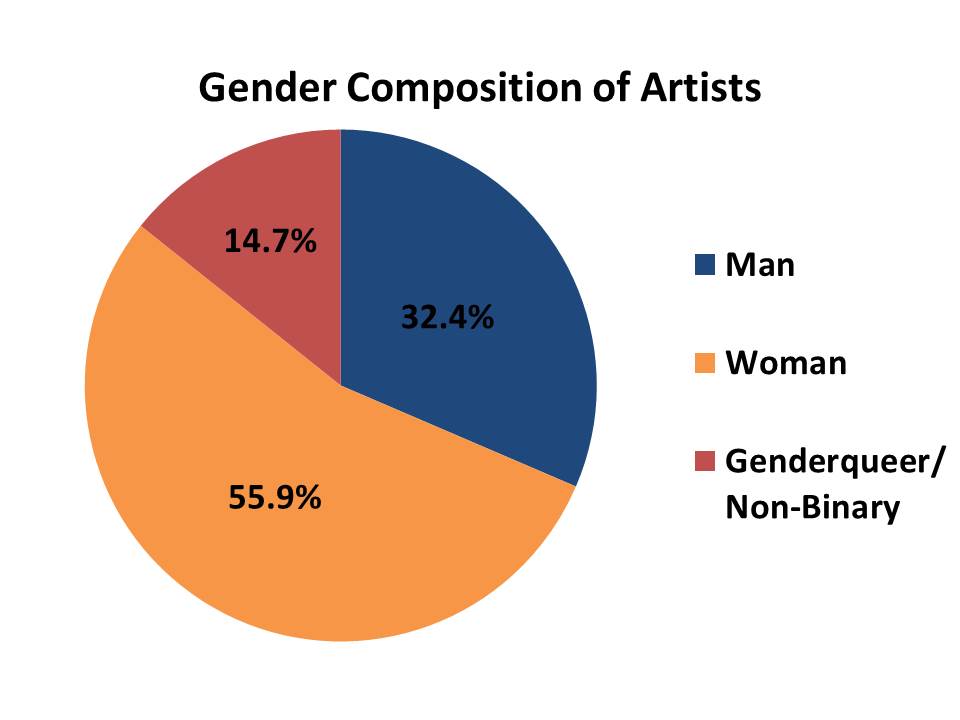

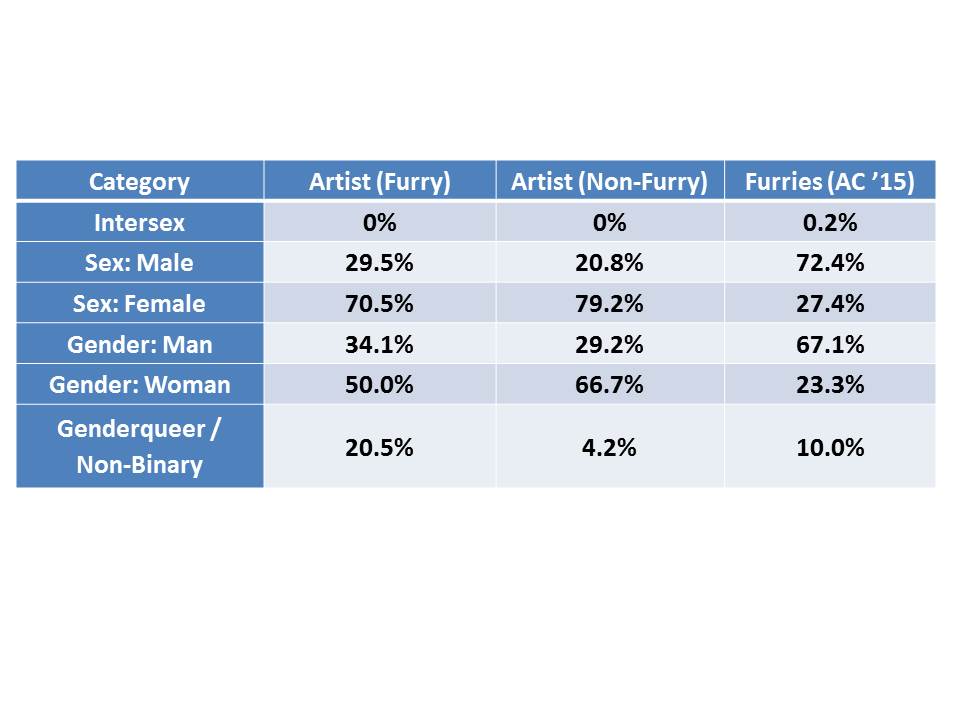

Short answer: Yes, absolutely. In fact, while the furry fandom, as a whole, is predominantly male (about 75%), artists in the furry fandom are almost equally predominantly female, with about 75% of furry artists self-identifying as such. Moreover, when asked about their gender (as opposed to their sex), we found that many people who indicated that their sex was female also indicated that they identified as a man or as genderqueer / non-binary, far more than those indicating that their sex was male, the vast majority of whom indicated they identified as a man.

Long answer: As the figures above illustrate, in a complete reversal of the trend found in the broader furry fandom, furry artists seem to be predominantly female. The IARP has been assessing self-identified gender separately from sex, recognizing that there are many people for whom their self-identified gender is either not represented by their body or who do not feel their gender identity falls into a “man/woman” dichotomy. Studying sex and gender this way has been particularly informative with regard to the artist sample, as it shows that 14.7% of artists self-identify as genderqueer or non-binary, information that would have been missed had we simply asked them to check “male” or “female”. Moreover, our findings suggest that a far higher proportion of females (as compared to males) indicated that they identified either as transgender or genderqueer. We are, as of yet, unsure why artists show such a dramatically different sex/gender composition compared to the rest of the furry fandom, and future research will be investigating this issue. However, it is worth noting that, in the past, we have suggested the possibility that the furry fandom as a whole, being predominantly male, may seem like a “boys club” to women. This may discourage women from joining the fandom, or it may preferentially select for people whose gender identity is more in-line with traditionally masculine traits. For females who have an “in”, however (e.g., “I’m an artist, I belong here”), they may find it easier to belong to the fandom. It remains for future research to these hypotheses.

As a final interesting note, the table below illustrates that furry artists, as compared to non-furry artists in our sample, were nearly 5 times more likely to self-identify as genderqueer/ non-binary, and were twice as likely to self-identify as such compared to the general furry population. The reasons for this are as-of-yet unknown, but represent an interesting finding for future research to explain.

2. Are furry artists older than furries in general?

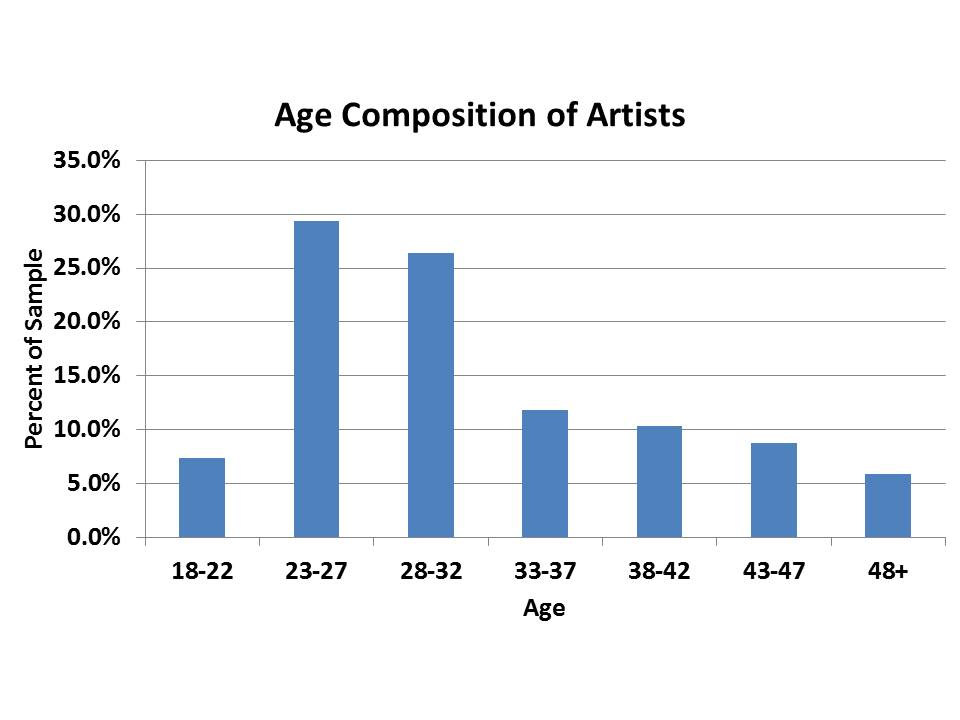

Short answer: Yes. Whereas the average furry has been found to be in their early-to-mid 20s, the average furry artist in our sample was in their early 30s. In addition, there is a far higher proportion of older furry artists than there are older furries in the broader fandom.

Long answer: The figure above shows that, unlike the age composition of the broader fandom, which is heavily positively skewed (e.g. most participants are under the age of 25, with very few participants in their 30s and older), the age composition of artists takes a somewhat different shape. In fact, rather than showing the greatest proportion of participants in the 18-22 range, we find that most artists in the Dealer’s Den are in their mid-to-late 20s. Moreover, there are far more artists in their mid-thirties and above (~35%) than there are furries in the general population in the same age demographic (~12%). It would seem, then, that furry artists, as a group, are older than the general furry population. This is likely, in part, due to the fact that our sample consisted of artists in the Dealer’s Den at Anthrocon, which means they were artists established enough in their careers / in the fandom to justify the cost of their table. As such, our sample likely draws upon artists who have been in the fandom for awhile or who have spent many years honing their craft. Going forward, we plan to study online artists in the fandom, to see whether this tendency for artists to be older than the general furry population holds outside of a convention setting.

3. Are artists who sell to furries also furries themselves?

Short / long answer: Yes and no; about two-thirds of artists in the fandom self-identify as furry (64.7%). The other third of artists indicated that they did not consider themselves to be a furry. Such cases may represent artists who have honed their craft in other fandoms / contexts (e.g., anime fandom), and who attend furry conventions to sell their art to furries. From what we’ve been able to tell so far, there are no significant differences between furry artists and non-furry artists on any of the measures we assessed.

4. Were furry artists furries first, or were they artists first?

Short answer: Most of the artists in our sample were artists long before they were furries.

Long answer: On average, those artists in our sample self-identifying as a furry said that they had been an artist for 18.62 years, but that they had been a furry for 11.26 years. This may be explained by the fact that many furries do not discover the fandom until well into their teenage years, given its relative obscurity in popular culture. In contrast, many artists likely discover an interest in art from a younger age, particularly those who go on to practice it enough to eventually become dealers and sell their work.

5. Do convention-going artists make their living solely by doing art?

Short / long answer: No; while the vast majority of artists who take on dealer spots at conventions said that they earned income from their artwork, only 32% said that the income they make from their art is their sole source of income. Most artists supplement their income with other employment or from other sources.

6. Do most furry artists have a posted “Terms of Service” or “Will not draw” list?

Short answer: Yes; 60% of the artists in our sample indicated that they had a Terms of Service posted (e.g., at their table, online), where commissioners / customers can read about the artist’s policies for commissions. 50% of the artists said that they also had a “will not draw” list, which includes a list of themes or content that they would not produce for commissioners.

Long answer: In the IARP’s prior work, which employed artist focus groups to inform us about relevant questions to artists, many artists indicated that they had, at one point or another, been asked to produce material they were uncomfortable with, been forced to deal with the same sorts of issues with commissioners, or had been subjected to treatment that they deemed unacceptable. As such, many artists stated that they tried to preempt these situations with a posted terms of service and/or a will not draw list. 60% of artists had a posted Terms of Service, while 50% had a will not draw list, substantiating what we found in our prior focus groups. In a series of follow-up questions, we found that 72.1% of artists had been asked, at least once, to produce content they were uncomfortable with, while 23.4% of artists actually produced content despite their reservations. In a subsequent analysis, we found that artists with a “will not draw” list were almost twice as likely (94.1% vs. 50.0%; t(46.9) = 4.59, p < .001) to have been asked to draw something they disagreed with and to produce something they felt uncomfortable with (35.3% vs. 10.0%; t(56.3) = 2.53,p = .014). While it’s impossible to discern the direction of causation of this relationship, we hypothesize that many artists who post a “will not draw” list do so after having been requested to draw / having drawn something they were uncomfortable with.

7. What sorts of issues do artists deal with?

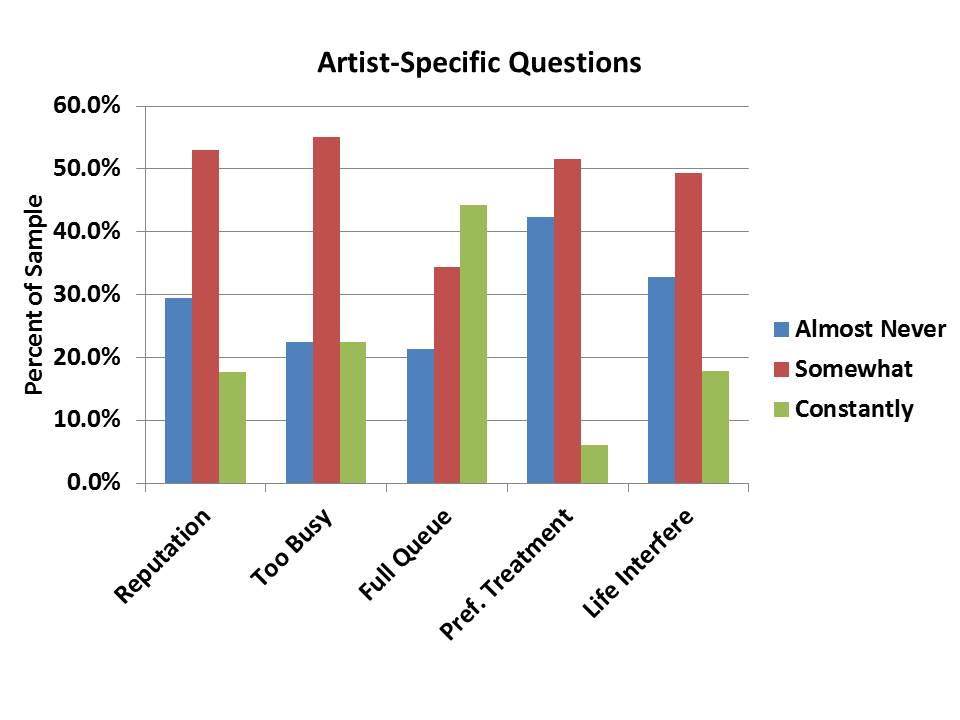

Short answer: We found evidence that most artists worry at least somewhat about their reputation, and most artists report having a full queue and consistently taking on too large a workload. Most artists also indicated that life sometimes interfered with their work. About half of artists agreed that they sometimes gave preferential treatment to some commissioners over others, though very few did so regularly. One-third of artists said that the work they never produced erotic content, while 17.6% of artists said that half or more of their work was erotic in nature, suggesting that while most artists produce at least some erotic content, few artists produce exclusively erotic content. Finally, about half of the artists in our sample said that their friends in the fandom were also artists.

Long answer: The figure above illustrates how the artists in our sample felt toward different artist-related issues. Not shown in the figure, 32.4% of artists said they produced artwork with no erotic content, and only 17.6% said that half or more of their artwork was explicit. Artists indicated that, on average, 59.7% of their friends in the fandom were also artists, suggesting that many artists interact with one another in a sub-community within the furry fandom. Such a subgroup may serve a number of important functions, from artists teaching other artists, sharing resources (e.g., equipment, table space at conventions), and as a source of social support. Given that artists say, on average, 6.2% of the comments they receive about their work are negative, the vast majority of the feedback they receive from the fandom is positive, though they may still turn to other artist friends for support in response to negative comments, for advice on dealing with difficult commissioners, or when, as we’ve seen, they take on too much work.

Long answer: The figure above illustrates how the artists in our sample felt toward different artist-related issues. Not shown in the figure, 32.4% of artists said they produced artwork with no erotic content, and only 17.6% said that half or more of their artwork was explicit. Artists indicated that, on average, 59.7% of their friends in the fandom were also artists, suggesting that many artists interact with one another in a sub-community within the furry fandom. Such a subgroup may serve a number of important functions, from artists teaching other artists, sharing resources (e.g., equipment, table space at conventions), and as a source of social support. Given that artists say, on average, 6.2% of the comments they receive about their work are negative, the vast majority of the feedback they receive from the fandom is positive, though they may still turn to other artist friends for support in response to negative comments, for advice on dealing with difficult commissioners, or when, as we’ve seen, they take on too much work.

8. What are, according to artists, the biggest problems that arise when dealing with commissioners?

Short/long answer: We asked artists indicate how commonly they encountered different problems when doing commission-based work for a customer. These items were generated from prior focus groups with artists. The top six issues, from biggest/most common issue to least-common, were:

- What the customer wants is vague / unclear.

- The customer’s expectations are unreasonable (e.g., completion time, resource cost, etc…)

- Communication problems with the customer (e.g., slow / no e-mail response, no way to get ahold of customer).

- Customer disagrees with prices (e.g., complains that they are unfair or too high, or that they could get a similar piece from a different artist for cheaper).

- Customer asks for something the artist is unable or unwilling to do (e.g., extreme content, a technique the artist is unfamiliar with).

- The customer is rude / hostile.

- Do artists think furries are entitled? Are furries entitled?

9. Do artists think furries are entitled? Are furries entitled?

Short answer: Our data suggest that most furries hold less-entitled attitudes than artists assume, and, in many instances, even have less-entitled attitudes than artists themselves hold. This may be due to the fact that a small number of “bad apples” (e.g., difficult commissioners, rude customers, demanding commenters) stand out in the minds of artists, causing them to over-estimate the entitlement of the average furry.

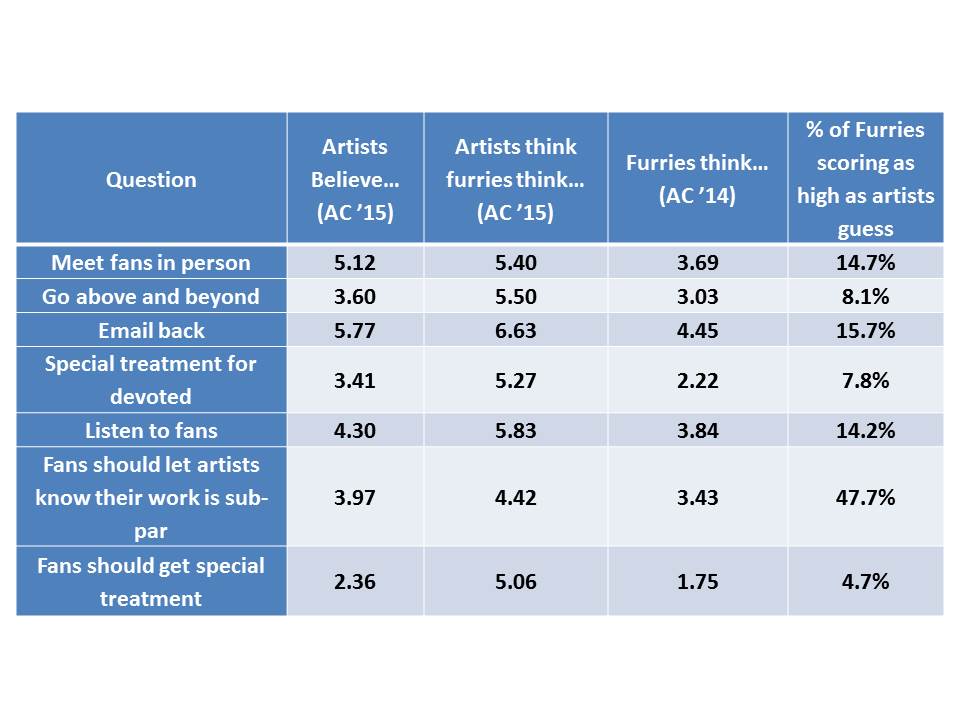

Long answer: The table above contains a series of seven questions assessing different elements of fan entitlement: should artists be expected to meet their fans in person, should they be expected to go above and beyond fan expectations, should artists be expected to e-mail fans/commissioners back, should devoted fans get special treatment, should artists be obligated to listen to their fans, should fans let artists know their work is sub-par, and should specific fans get special treatment from artists. The extent to which participants agreed could be indicated using a 7-point scale (1 – Strongly Disagree, 7 – Strongly Agree). In 2014, we asked these questions to furries attending Anthrocon (the “Furries think” category). This year, we asked artists how they personally felt about each of these issues (“Artists believe”). It’s clear that while artists score below the midpoint (4.00) on many of these items, furries, as a whole, score even lower than artists in terms of felt entitlement on every single one of these items. Finally, we asked artists to estimate how the average furry would answer the same questions (“Artists think furries think”), and in every case, artists significantly over-estimated how entitled the average furry felt (the right-most column shows the percentage of furries who scored as high or higher than the artist’s estimate, rounded to the nearest whole number).

Despite the fact that most furries scored lower than the artists themselves on the entitlement questions, artists believed that most furries were nevertheless entitled. This may be due to a phenomenon called the availability heuristic: when estimating how frequently something occurs, people’s estimates are significantly impacted by very poignant, extreme events that stand out in their memory. As such, if an artist is trying to estimate how entitled furries are, examples of particularly entitled commissioners (who are, as we can see, statistically rare) may spring to mind first, entirely because they are unusual. This might lead artists to overestimate how entitled most furries are, though it remains for future research to test whether the availability heuristic explains this phenomenon.

Part 2: General Population Survey

1. Do furries feel “young at heart” – that is, younger than their actual age?

Short answer: Not necessarily – the data show that furries are like the average person when it comes to felt age: younger furries tend to feel older / more mature than their actual age, while older furries tend to feel younger than their actual age.

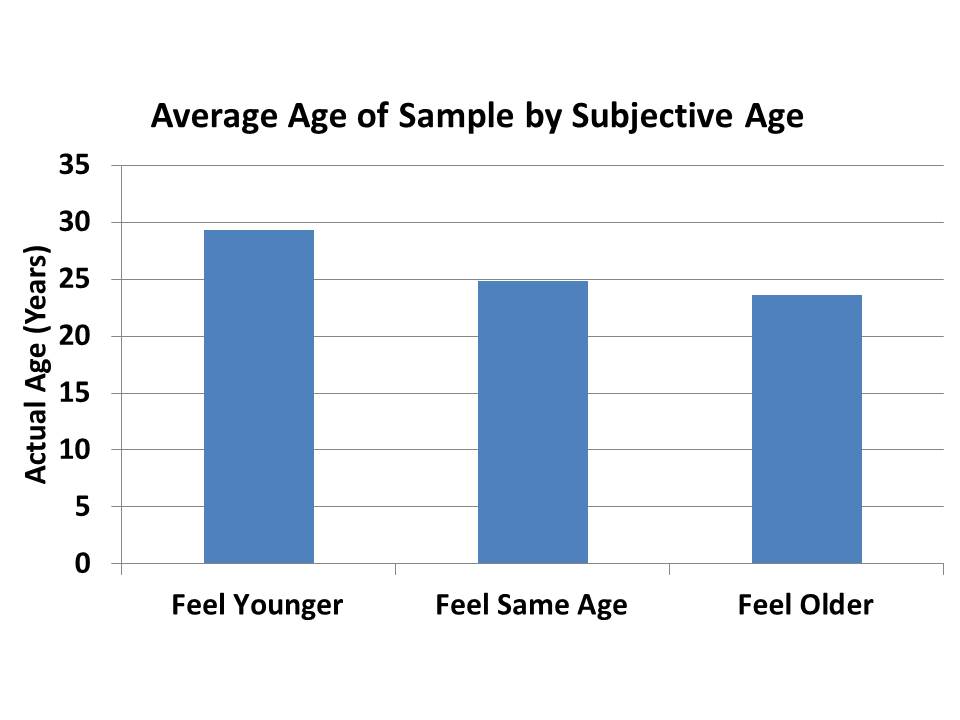

Long answer: We followed up on some of our previous subjective age research to test whether furries, like others who have been studied in subjective age research, tend to feel older or younger than they actually are. Given that fantasy is traditionally assumed to be something that children engage in, we hypothesized that furries, unlike most people, might, as a group, be inclined to see themselves as younger than their actual age. However, the results find that furries show the same pattern of results at other groups who have been studied: the older you are, the younger you feel, and vice-versa. Put another way, actual age significantly negatively predicts subjective age (F(1,913) = 103.20, p<.001, Beta = -.32). To illustrate this, in the figure above we divided participants into three categories: those who said they feel younger than they actually are (45.4% of participants), those who said they felt their age (34.8%), and those who felt older than they actually are (19.9%). When we calculated the average of these three groups, those who said they felt younger were older than those who said they felt older.

As a follow-up, we calculated how much older or younger participants felt than their current age. On average, those who reported feeling older felt about 48.1% older than their current age, while those who felt younger felt, on average, 26.9% younger than their current age; put another way, those in their 30s felt like they were in their early 20s, while those in their 20s felt like they were in their early 30s. Those in their mid-twenties felt that they were about their actual age.

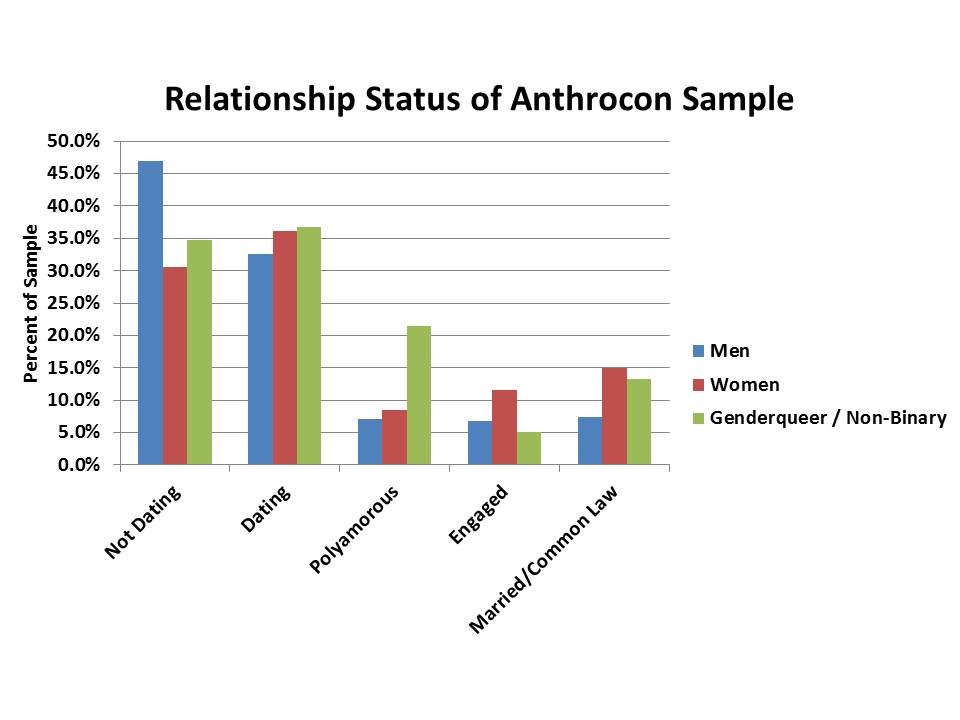

2. Do furries’ relationship statuses differ by gender?

Short / long answer: Yes; men are more likely to indicate that they are currently “not dating” than women or genderqueer / non-binary participants. Women, on the other hand, were more likely to be engaged or married. Finally, genderqueer / non-binary participants were the most likely of the three groups to indicate that they were in a polyamorous relationship (more than twice as likely to be so). The groups were comparable with regard to the proportion of members who indicated they were “dating”.

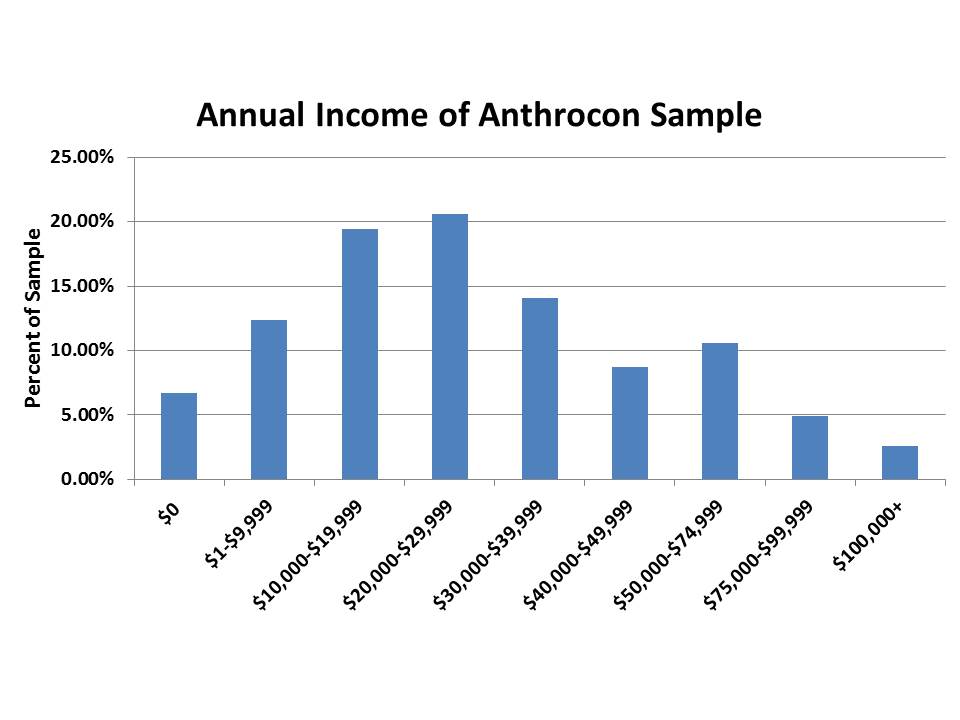

3. Are furries, as a group, relatively low-income?

Short / long answer: Generally speaking, yes: the data show that more than half of furries in our sample earned less than $30,000 / year, and just over 5% of furries had no annual income. By comparison, only about 7.5% of furries earned more than $75,000 / year. That said, it is worth noting that the sample in question is based on Anthrocon attendees – these participants have the resources to attend a convention (which usually includes, travel, hotel, and admission costs), meaning furries who were unable to attend the con for financial reasons were not represented. As such, the “real” rates of low-income furries are likely to be higher than what is shown here. We believe this is likely due, in no small part, to the fact that many furries are in college or the fact that, as a group, furries are relatively young (and are thus, like many in their teens / early twenties, not yet in a stable career). In future, online studies, we aim to compare the income of convention-going furries with that of online furry samples, and are interested in the possible restricting impact that income may have on convention attendance and on other forms of fandom participation (e.g., purchasing a fursuit, going to local meet-ups, etc…)

4. Are furries religious? Spiritual?

4. Are furries religious? Spiritual?

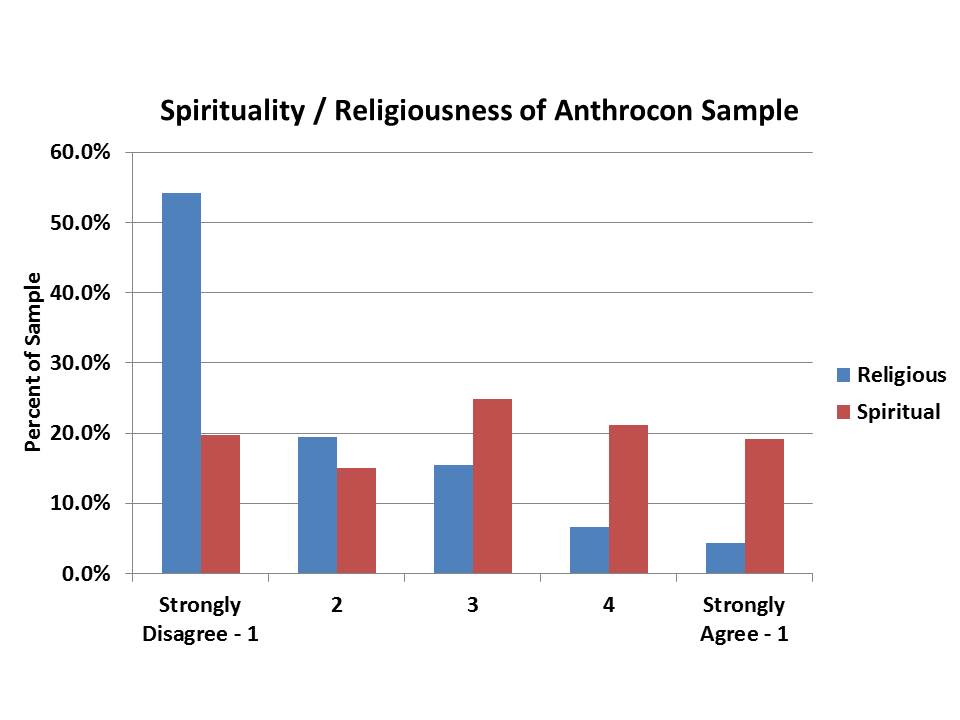

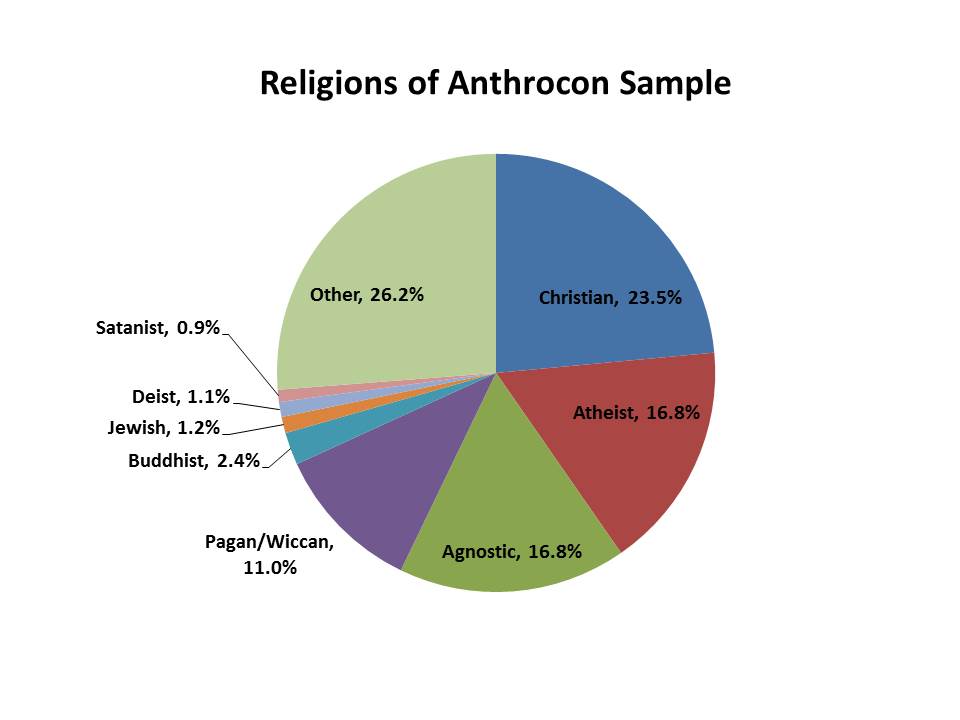

Short answer: Furries, as a group, are not particularly religious, though they are more likely to indicate that they are at least somewhat spiritual. Most furries self-identify as atheist/agnostic, followed by Christian. Wiccan / Pagan / Shamanistic belief systems are also present in the fandom. About a quarter of furries indicated that they belonged to idiosyncratic, “undecided”, or “other” belief systems.

Long answer: While the majority of furries indicated that they did not consider themselves to be religious (blue bars above), the fandom was far more diverse with regard to spiritual beliefs, with furries being about equally likely to indicate either that they were spiritual or not (red bars above). These findings are corroborated by another question asking participants to indicate what their religious beliefs, if any, were (see table below). About one-third of furries indicated that they were either atheist or agnostic, which corresponds to the approximately 35% of furries stating that they did not consider themselves to be particularly spiritual. About 25% of furries indicated that they were Christian, though many also indicated that they adhered to the general beliefs of Christianity without regularly practicing or attending church (as reflected by the relatively small number of participants indicating they were strongly religious). Many furries (11%) also indicated pagan, shaman, or Wiccan belief systems. Finally, the most populated category, “other” was comprised of participants with belief systems they came up with on their own, who were undecided, who refused to answer, or with other, less common belief systems. These findings are relatively consistent with our findings regarding furry spirituality from several years prior. Taken together, the data suggest that the diversity of the furry fandom extends to a diversity of religious beliefs as well, and its’ worth noting that despite the diversity of beliefs, religion is seldom a point of conflict among furries.

Long answer: While the majority of furries indicated that they did not consider themselves to be religious (blue bars above), the fandom was far more diverse with regard to spiritual beliefs, with furries being about equally likely to indicate either that they were spiritual or not (red bars above). These findings are corroborated by another question asking participants to indicate what their religious beliefs, if any, were (see table below). About one-third of furries indicated that they were either atheist or agnostic, which corresponds to the approximately 35% of furries stating that they did not consider themselves to be particularly spiritual. About 25% of furries indicated that they were Christian, though many also indicated that they adhered to the general beliefs of Christianity without regularly practicing or attending church (as reflected by the relatively small number of participants indicating they were strongly religious). Many furries (11%) also indicated pagan, shaman, or Wiccan belief systems. Finally, the most populated category, “other” was comprised of participants with belief systems they came up with on their own, who were undecided, who refused to answer, or with other, less common belief systems. These findings are relatively consistent with our findings regarding furry spirituality from several years prior. Taken together, the data suggest that the diversity of the furry fandom extends to a diversity of religious beliefs as well, and its’ worth noting that despite the diversity of beliefs, religion is seldom a point of conflict among furries.

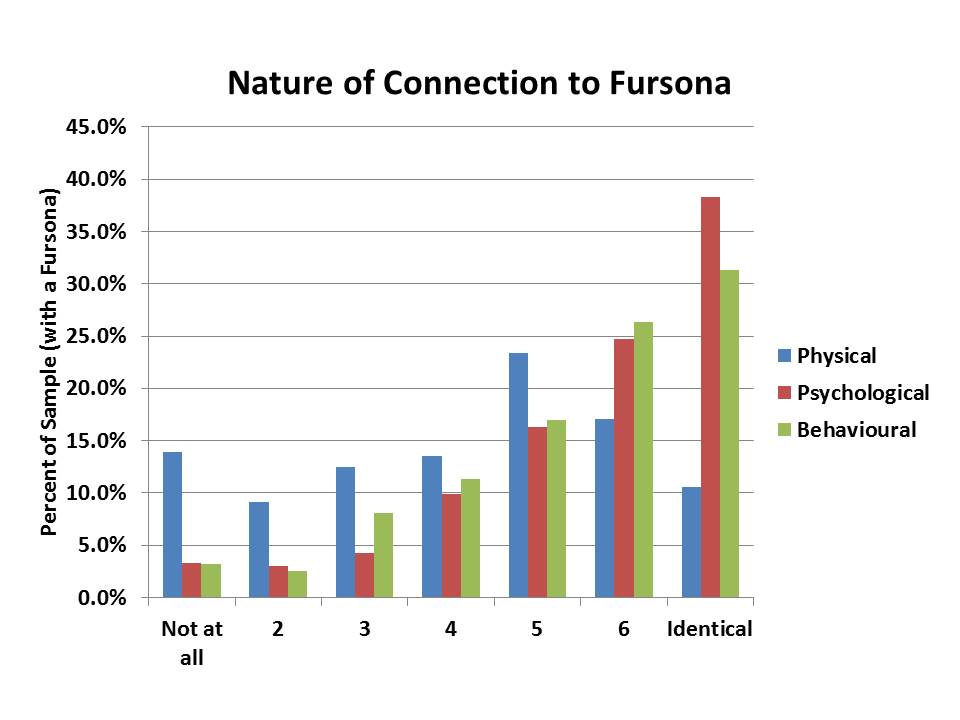

5. What is the nature of furries’ felt connection to their fursonas – if there is one at all?

Short answer: Furries typically report feeling a sense of connection to their fursonas, though the nature of this connection can vary widely. In general, furries are most likely to indicate that they feel psychologically similar to their fursona, and somewhat behaviourally similar to their fursona. They are far less likely, though not unlikely, to say that they feel physically similar to their fursona.

Long answer: We asked furries who had a fursona to indicate, on a 7-point scale, the extent to which they felt similar to their fursona physically, psychologically, and behaviorally. On average, participants felt psychologically closest to their fursonas (M = 5.60), followed closely by feeling behaviourally similar to their fursonas (M = 5.41), while, by comparision, they felt far less physically similar to their fursonas (M = 4.17). The significance of these differences was tested with a repeated measures ANOVA (F(2,925) = 368.35, p <.001) and was found to be significant. Follow-up paired samples t-tests revealed that the three measures were statistically significantly different from one another (all t’s > 4.43, all p-values < .001). In sum, while furries feel connected to their fursonas, and often feel similar to their fursonas, the nature of this connection is predominantly a psychological and behavioural one, and not a matter of furries believing that they are physically their fursona (although they may share some physical traits with their fursona; for example, large people identifying with bears, small people identifying with mice, etc…) In future studies, we would like to further study the nature of these felt similarities: what sorts of traits make a person feel psychologically / behaviorally / physically similar to their fursona?

Long answer: We asked furries who had a fursona to indicate, on a 7-point scale, the extent to which they felt similar to their fursona physically, psychologically, and behaviorally. On average, participants felt psychologically closest to their fursonas (M = 5.60), followed closely by feeling behaviourally similar to their fursonas (M = 5.41), while, by comparision, they felt far less physically similar to their fursonas (M = 4.17). The significance of these differences was tested with a repeated measures ANOVA (F(2,925) = 368.35, p <.001) and was found to be significant. Follow-up paired samples t-tests revealed that the three measures were statistically significantly different from one another (all t’s > 4.43, all p-values < .001). In sum, while furries feel connected to their fursonas, and often feel similar to their fursonas, the nature of this connection is predominantly a psychological and behavioural one, and not a matter of furries believing that they are physically their fursona (although they may share some physical traits with their fursona; for example, large people identifying with bears, small people identifying with mice, etc…) In future studies, we would like to further study the nature of these felt similarities: what sorts of traits make a person feel psychologically / behaviorally / physically similar to their fursona?

6. How many people are therians, and do therians experience phantom limb syndrome?

Short answer: Approximately 7% of our sample self-identified as therian. Compared to non-therian participants, therians were nearly six times more likely to indicate that they often experience phantom limbs / tails – that is, the sensation of having a limb/tail when one is not physically present. About half of strongy-identified therians indicate that they experience at least some significant distress at the feelings associated with therianthropy (that is, identifying psychologically, spiritually, or physically with a non-human animal species).

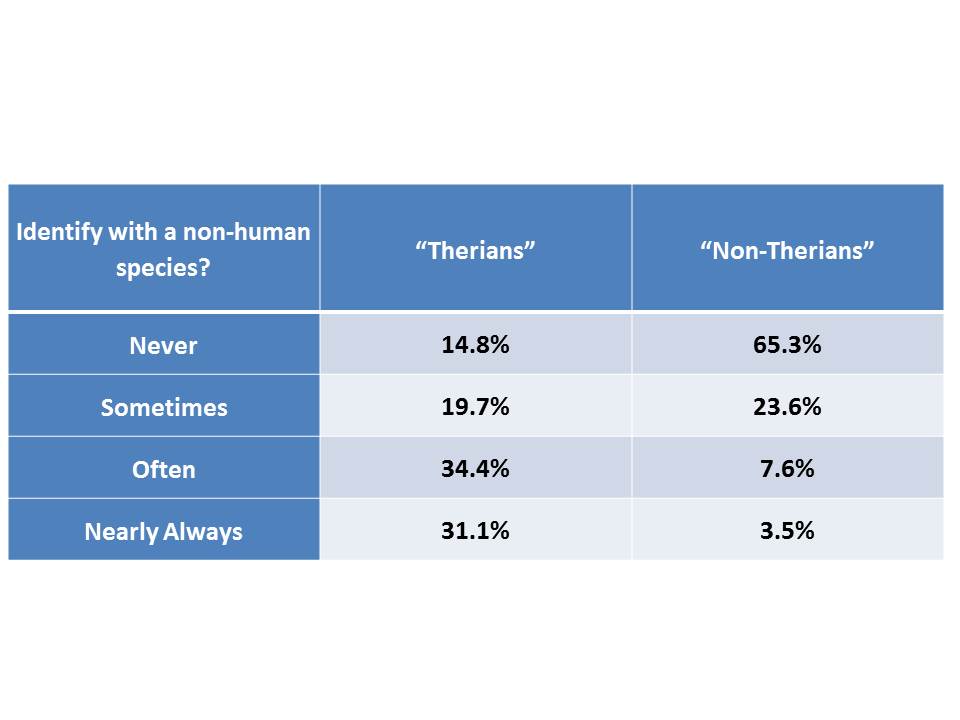

Long answer: For the past few years the IARP has been interested in the phenomenon of therianthropy – trying to understand self-identified therians, in part to reduce the stigma associated with therianthropy. Presently, we asked participants to indicate if they considered themselves a therian or not. Later, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which they felt that they are a non-human species of animal (see figure above). Interestingly, while most therians agreed at least somewhat with this statement, 14.8% of therians did not. This suggests two possibilities: a) some people on the survey indicated that they were a therian without knowing what a therian was, or b) there is no one, agreed-upon definition of what a therian is (or, if there is, it is not the definition we have empirically derived from our qualitative work with therians). Another set of questions on the survey asked participants to provide their own definition of what they believed a therian was – the results of which, when coded, may help to shed light on any failings of our current definition. Also interesting to note – 11.1% of non-therian participants indicated that they often or nearly always felt like they were a non-human species of animal, suggesting that there may be a number of people who, without knowing the term, nevertheless identify with many of the experiences associated with therianthropy.

Long answer: For the past few years the IARP has been interested in the phenomenon of therianthropy – trying to understand self-identified therians, in part to reduce the stigma associated with therianthropy. Presently, we asked participants to indicate if they considered themselves a therian or not. Later, we asked participants to indicate the extent to which they felt that they are a non-human species of animal (see figure above). Interestingly, while most therians agreed at least somewhat with this statement, 14.8% of therians did not. This suggests two possibilities: a) some people on the survey indicated that they were a therian without knowing what a therian was, or b) there is no one, agreed-upon definition of what a therian is (or, if there is, it is not the definition we have empirically derived from our qualitative work with therians). Another set of questions on the survey asked participants to provide their own definition of what they believed a therian was – the results of which, when coded, may help to shed light on any failings of our current definition. Also interesting to note – 11.1% of non-therian participants indicated that they often or nearly always felt like they were a non-human species of animal, suggesting that there may be a number of people who, without knowing the term, nevertheless identify with many of the experiences associated with therianthropy.

In another series of questions, we asked participants to indicate whether or not they had ever experience phantom body parts (e.g., limbs, tails, feathers; see below). Therians were significantly more likely to indicate that they had experienced phantom body parts (M = 2.57) than non-therians (M = 1.49; t(66.2) = 8.18, p <.001). Among those experiencing phantom body parts frequently, 70.4% found it to be “sometimes” or “always” distressing. Finally, we asked participants to indicate whether therianthropic experiences caused them distress. Of those indicating that they always felt therianthropic experiences, 54.7% found it “sometimes” or “always” distressing, while 43.4% said that they never found it distressing.

7. What can furries tell us about the way people experience fantasy?

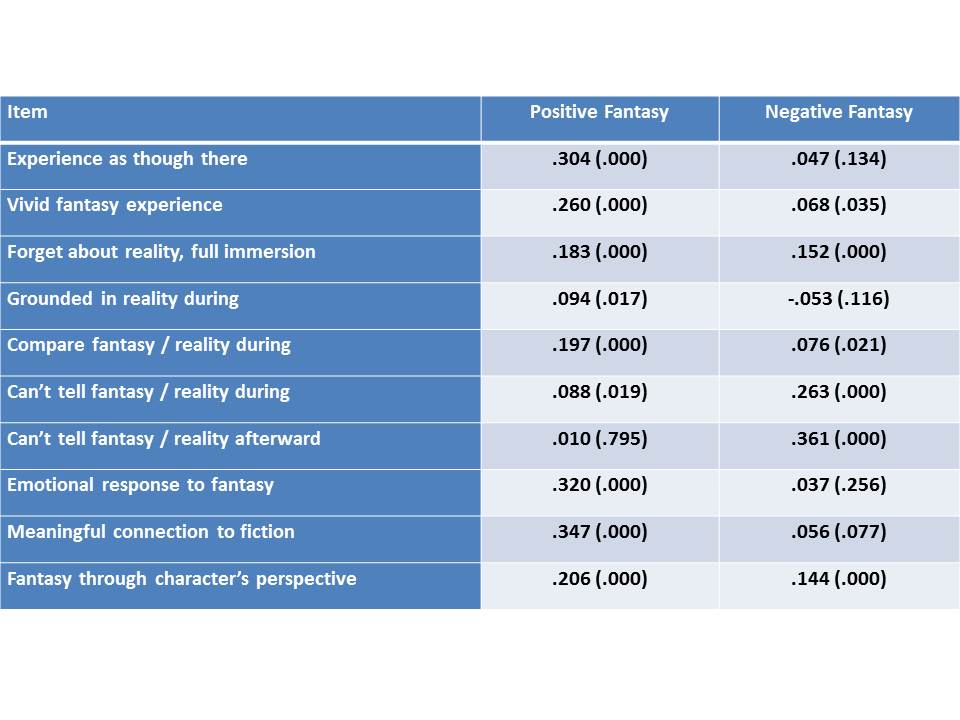

Short answer: As a matter of fact, lots! Prior research has shown that people can engage in fantasy in positive ways (e.g., inspiration, entertainment), or they can engage in fantasy for more problematic reasons (e.g., escapism, blurring fantasy and reality). Furries have been shown to be associated much more strongly with the “positive” form of fantasy engagement. In this follow-up study, we’ve also found that there are significant differences in the way “positive” and “negative” fantasy are experienced: in positive fantasy, people experience fantasy worlds vividly, putting themselves fully in the experience, becoming emotionally responsive to the experience, feeling meaningful connections with the fantasy, all while comparing what the experience to reality. In contrast, none of those things happen for people experiencing more negative forms of fantasy, in which the goal may not be to immerse oneself in another world but, instead, solely to distract oneself from reality.

Long answer: Prior research has shown that people can engage in fantasy in positive ways (e.g., inspiration, entertainment), or they can engage in fantasy for more problematic reasons (e.g., escapism, blurring fantasy and reality). Furries have been shown to be associated much more strongly with the “positive” form of fantasy engagement. In the present study, we’ve tested the extent to which positive and negative forms of fantasy are associated with different experiential aspects of fantasy engagement. In particular, participants were asked a series of questions about the nature of their experience with fantasy (e.g., do you experience meaningful connections with fantasy worlds / characters, do you respond emotionally to fantasy?) The table above shows the result of a series of regression analyses, allowing both positive and negative fantasy engagement to simultaneously predict each of the outcome variables. The first value in each box indicates the regression coefficient (higher number = stronger association, negative number = negative association), while the number in the brackets indicates the p-value (p

8. Are there gender differences in the experience of belongingness, objectification, or discomfort / insecurity in the fandom?

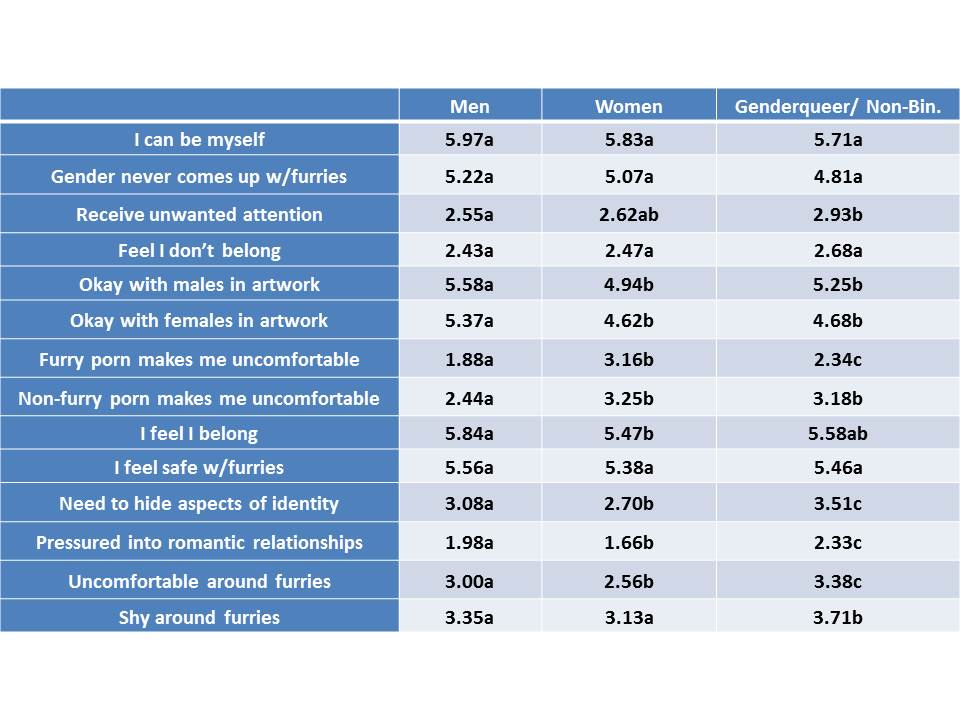

Short answer: Yes; compared to men, women were less comfortable with the portrayal of males and females in furry artwork, were more uncomfortable with pornography (furry and non), and felt less like they belonged in the furry fandom. However, men and women did not differ in the extent to which they felt they could be themselves in the fandom, in the extent to which their gender was an issue in the fandom, the amount of unwanted attention they received, feeling like they don’t belong in the fandom, feeling safe around furries, and feeling shy around furries. Moreover, women felt less need to hide aspects of their identity than men, felt less pressured into romantic relationships than men, and felt less uncomfortable around furries than men. Interestingly, genderqueer / non-binary participants, compared to men and women, reported feeling significantly more unwanted attention from furries, felt a greater need to hide aspects of their identity from members of the fandom, felt more pressured into romantic relationships, and felt more shy and uncomfortable around other furries. This work represents an extension of our previous research on gender issues in the fandom, which, over the past two years, has involved focus groups, targeted surveys, and, finally, large-scale survey data directly comparing men, women, and genderqueer / non-binary participants.

Long answer: Several years ago the IARP presented initial findings from a focus group on gender issues in the fandom suggesting that women in the fandom may experience discomfort at being a minority in a predominantly male fandom. Given the qualitative nature of the findings, we next conducted a small-scale study of women, which quantified these issues, illustrating which were the most prevalent for women. However, many critics rightly pointed out that without comparing these numbers to men, they meant very little. As such, at Anthrocon we asked a broad array of questions related to the issues raised by women in the focus groups nearly two years ago. These questions were answered by both men and women, and allow us to test whether the issues raised by women are unique to women or are experienced by men, women, and non-binary genderqueer participants in the fandom.

The table above presents the average response for each group on a 7-point scale (1 – Completely Disagree, 7 – Completely Agree). The letters following the averages portray the results of a series of t-tests: if two groups share the same letter for any given row (e.g., Men = A, Women = A), it means that the groups did not differ statistically significantly. If the two groups have different letters (Men = A, Women = B), it means that these groups differed statistically significantly from one another.

The data indicate that there are some issues in which women seem to experience greater distress or discomfort than men. For example: women are significantly more likely than men to say that they were uncomfortable with the way men and women were portrayed in furry artwork, and were less comfortable with pornography than men altogether. Women were also less likely to say that they felt they belonged in the fandom (though they did not necessarily feel that they didn’t belong either). That said, there were also a number of issues in which men felt greater distress than women – men reported feeling a greater need to hide aspects of their identity around furries, felt more pressured into romantic relationships from other furries, and felt more uncomfortable around other furries than women. Finally, men and women did not significantly differ from one another on several variables of interest, including feeling that they can be themselves in the fandom, feeling that their gender never comes up, receiving unwanted attention from other furries, and feeling safe / shy around other furries. Taken together, these data suggest that while there are some sources of distress in the fandom that are significantly higher for women than for men, there are also sources of distress for men that are significantly higher; moreover, several of the issues thought to be unique to the experience of women were also just as prevalent in the experience of men in the fandom.

Analysis of genderqueer / non-binary participants revealed that there are also some significant issues experienced by genderqueer / non-binary members of the fandom: these participants were, like women, uncomfortable with the portrayal of males and females in artwork, and were uncomfortable with pornography (though less uncomfortable with furry-themed pornography than women); genderqueer / non-binary participants were also significantly more likely to feel the need to hide their identity from other furries, felt more pressured into romantic relationships by other furries, and felt more shy / uncomfortable around furries than men and women.

It is worth noting, as a final point, that these data are not meant to be prescriptive or to dictate what “ought” to be the case in the fandom. In no way are the data intending to suggest that proportions of men, women, and genderqueer are “wrong”, nor are they intended to suggest that any one group of furries are maliciously attempting to trivialize, stigmatize, or prevent another group from entering the fandom. Nevertheless, the data do suggest that these perceptions are present among members of the fandom.

Part 3: Post-Convention Survey

1. Can furries “be themselves” at conventions more than in their day-to-day life?

Short answer: Yes: compared to their time at Anthrocon, furries report feeling, in their “day-to-day” lives (post-con), more self-consciousness – greater worry about what others will think of them, more fear that others will disapprove of them, greater concern with the impression they’re making on others, etc… than they felt at Anthrocon.

Long answer: To assess self-consciousness, we gave furries a 12-item self-consciousness scale including items such as “I am afraid others will not approve of me” and “I often worry that I will say or do the wrong things” (1 – Not at all, 6 – Extremely). Participants were given this survey at Anthrocon and again in the post-survey follow-up. Their scores on each scale were averaged and were then compared to one another. Scores at Anthrocon were lower (M = 3.54) than scores post-Anthrocon (M=4.15). These differences were found to be statistically significantly different using a paired-samples t-test (t(111) = 6.30, p < .001). In sum, there is truth to furries’ claims that furry conventions represent spaces where they can feel free to be themselves without inhibition or self-consciousness.

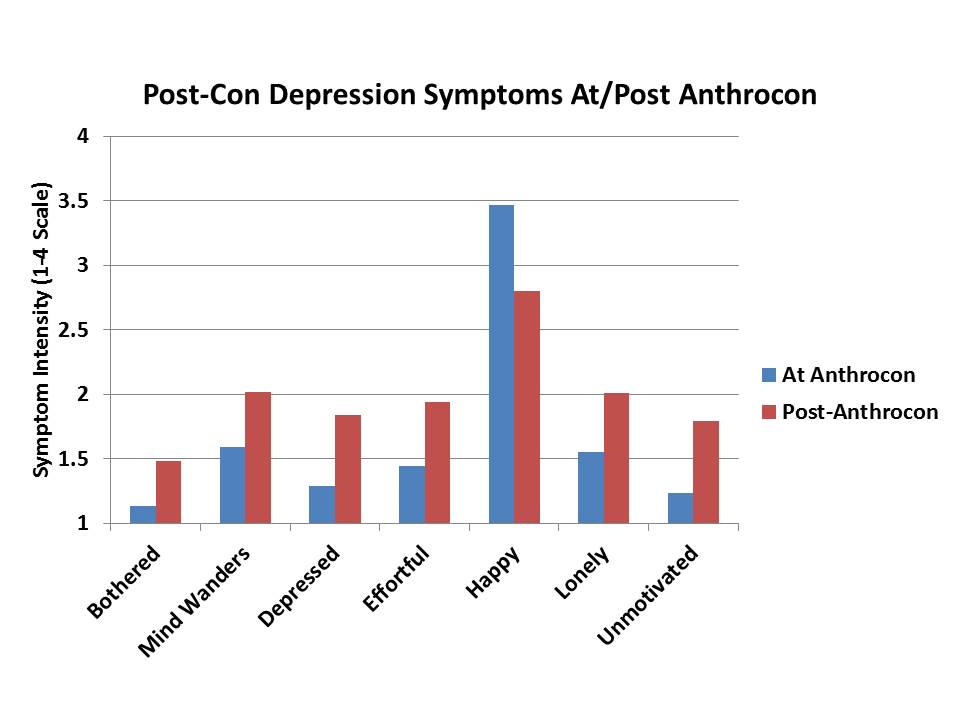

2. Is there such a thing as “post-con depression?”

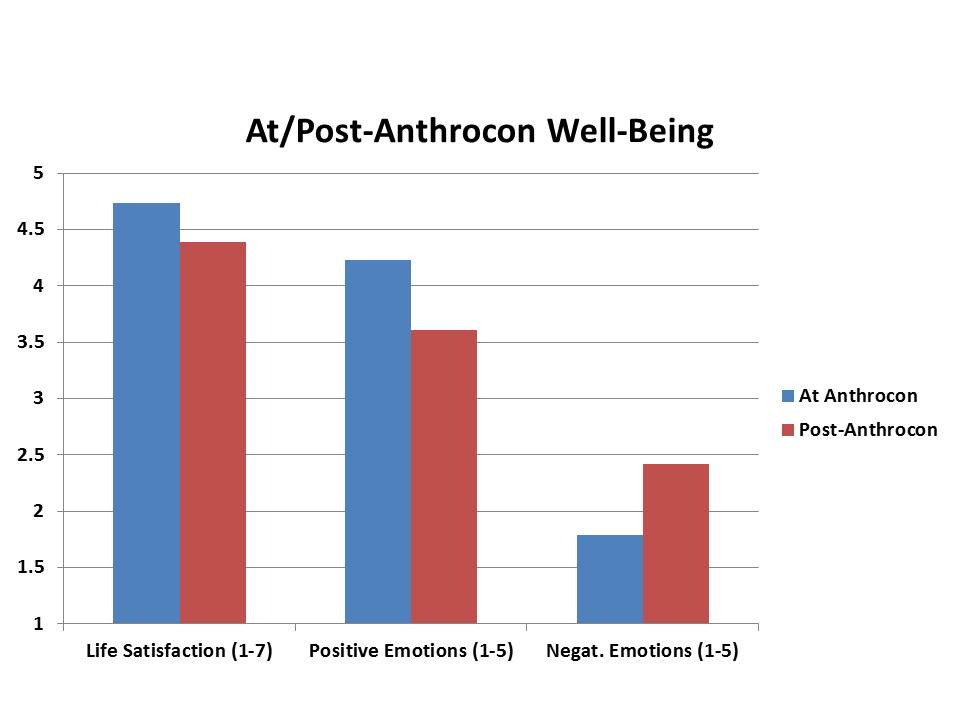

Short answer: Absolutely, yes. No matter how we measured psychological well-being (life satisfaction, positive emotions, lack of negative emotions, lack of depression, motivation…) furries reported feeling significantly less psychological well-being in the days following the convention. Unexpectedly, these feelings did not dissipate by a week after the convention.

Long answer: To assess post-con depression, we used a number of different existing psychological measures of psychological well-being. These measures were given to furries both at Anthrocon and again, 3 or 7 days post-Anthrocon. We assessed differences between these scores and tested, using repeated-measures t-tests, whether there was a statistically significant difference between the two time points. Without exception, furries reported less psychological well-being following the convention as compared to at the convention, which may be indicative of post-con depression. We will present these results one-at-a-time below.

Life satisfaction (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to ideal”) at the convention (M = 4.74) was significantly higher than life satisfaction after the convention (M = 4.39; t(111) = 3.28, p = .001).

Positive emotions (as assessed by the PANAS – Positive and Negative Affect Scale, e.g., “happy”) were significantly higher at the convention (M = 4.23) than after the convention (M = 3.61, t(109) = 7.91, p<.001).

Negative emotions (also assessed by the PANAS, e.g., “sad”) were significantly lower at the convention (M = 1.79) than after the convention (M = 2.42, t(109) = 8.12, p<.001).

Furries were less bothered by things that didn’t usually bother them at the con (M = 1.13) than after the con (M = 1.48, t(111) = 4.41, p<.001).

Furries had trouble keeping their mind on what they were doing less at the con (M = 1.59) than after the con (M = 2.02, t(111) = 4.37, p<.001).

Furries felt less depressed at the con (M = 1.29) than after the con (M = 1.84, t(111) = 5.84, p <.001).

Furries felt like everything took more effort after the con (M = 1.94) than at the con (M = 1.44, t(110) = 5.48, p <.001).

Furries felt happier at the con (M = 3.47) than after the con (M = 2.80, t(107) = 7.94, p<.001).

Furries felt less lonely at the con (M = 1.55) than at after the con (M = 2.01, t(110) = 4.81, p<.001).

Furries felt like they couldn’t get going motivationally more after the con (M = 1.79) than at the con (M = 1.23, t(111) = 6.70, p <.001).

Taken together, these data show not only that furries feel sad in the days following a furry convention, but that they also experience symptoms of fatigue, inability to focus, and irritability, all of which suggest a depressive mood. Moreover, findings (not presented here) also found that there was little to no difference between those furries completing the survey 3 days after the con to those completing it 7 days after the con. This may suggest that post-con depression may last longer than we had initially thought – perhaps spanning weeks instead of days. These data are, to our knowledge, the first empirical evidence demonstrating the phenomenon commonly referred to as post-con depression. Future studies will aim to not only better understand what this phenomenon entails and how long it lasts, but will also be focused on trying to reduce its effects.

Recent Comments