Note: this information is summarized from surveys and focus groups at a number of events across 2019, including Texas Furry Fiesta, Anthrocon, Eurofurence, and FurScience online surveys.

Convention Attendance:

Attendees at Anthrocon 2019, Eurofurence 2019, or in an online sample which took place at the same time as these conventions were asked to indicate the number of furry conventions they had ever attended. The data show that among the sample (which, to be clear, was predominantly convention-going furries), the most common single answer was one convention. That said, most of the sample indicated they had been to multiple conventions in the past, with about one-third of the sample indicating that they had been to 6 or more conventions. In short, the data suggest that not only do most furries end up attending at least one furry convention at some point, but the vast majority end up attending more than one convention.

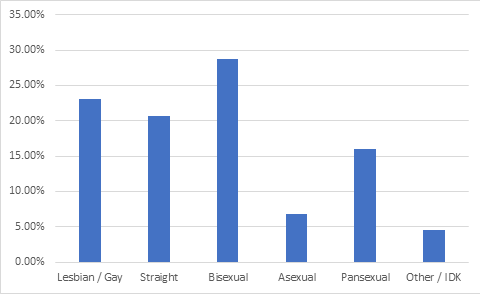

Sexual Orientation:

Based on combined Anthrocon 2019 / Eurofurence 2019 / Online 2019 data, participants were asked about their sexual orientation. Results essentially replicate what’s been found in past studies (e.g., Anthrocon 2018), but using a larger and more inclusive dataset. This supports the resiliency of prior findings that the furry fandom is predominantly non-heterosexual.

Socioeconomic Status:

Based on combined Anthrocon 2019 / Eurofurence 2019 / Online 2019 data, participants were to indicate which of several different labels best described their current socioeconomic status. In conjunction with past research (e.g., research employing a visual “ladder” measure), the result suggest that most furries consider themselves to be somewhere in the middle class, with relatively few furries in the lowest or highest rungs of the socioeconomic scale.

Fantasies:

In a combined study of Anthrocon 2019 / Eurofurence 2019 / and an online 2019 study, furry participants were asked a number of questions about the nature of their furry-themed fantasies—regardless of what those activities actually entailed. These ranged from simply having a fursona and thinking about it to attending conventions to playing furry-themed games or daydreaming about being a furry character. We were primarily interested in the characteristics of those furry-themed fantasies and the characters and activities they involved.

The above figure illustrates that furries were more likely to fantasize about activities and events that differed from their day-to-day lives (e.g., events that were unusual), although a fair number of furries also indicated that their activities involved fairly mundane activities as well (e.g., being one’s fursona at their place of work or in their home life).

Speaking to a similar idea as the previous point, the above figure illustrates that furries are more likely to fantasize—at least when it comes to furry-themed fantasies—about things that could never be instead of fantasizing about plausible occurrences. What this means remains to be seen in future research. For example, with current technology, being one’s fursona in day-to-day life is not possible. However, some people may have interpreted the question as referring less to being one’s fursona and more having to do with whether or not the activities themselves were possible (e.g., being a superhero, having special powers, time travel, etc.) Regardless, it would seem that furries are more likely to imagine things that never could be than things that could be, giving their furry-themed fantasy activities an extra element of “fantasy.”

In line with our prior findings suggesting that furries tend to create fursonas that represent idealized versions of themselves, furries were far more likely to indicate that their furry fantasies involved idealized facets of themselves rather than facets of themselves that others think they should be or worse elements of themselves. In other words, for most furries, furry-themed fantasy seems to have an element of “wishful thinking” to it, rather than being used as a tool of self-deprecation or as a means of trying to imagine oneself living within the demands of others.

We asked furries whether the furry-themed fantasies they had originated primarily from within themselves, was entirely created by others, or a mixture of both. Illustrating the contrast: A film like Star Wars is entirely created by someone else, although creating one’s own character to exist within the Star Wars universe might qualify as being both self- and other-created. It would seem from the above figure that most furries’ fantasies involve both self-created and other-created elements.

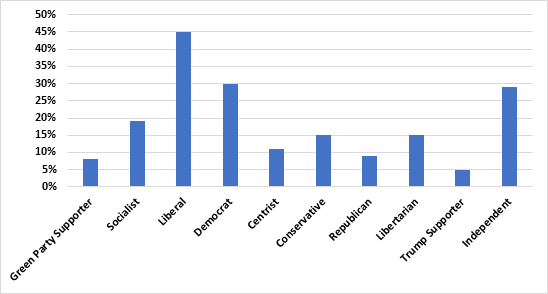

Political Orientation:

In previous years we attempted to assess political orientation in a rather superficial fashion. More recently, we have attempted to do a more in-depth, nuanced dive into the different facets of furries’ political ideology as a group. This research was carried out at Furry Fiesta 2019 in Dallas, Texas. As such, results should be treated with a grain of salt, given that they reflect a predominantly American sample taken from a fairly conservative part of the country. That said, the following results illustrate a strong liberal bias to furries even in a fairly conservative part of a fairly conservative country, suggesting that future research employing these same measure would likely find that the liberal slant toward furries is even stronger than what’s reported here.

The above two figures represent the labels that furries apply to themselves. Participants were given a large list of political labels and asked to check off any which they felt applied to them (they were not mutually exclusive categories.) As can be seen, furries were far more likely to indicate liberal labels (e.g., “liberal”, “democrat”, “socialist”) than more conservative labels (e.g. “conservative”, “republican”, “Trump supporter.”) It should also be noted that approximately 15% of furries considered themselves to be libertarian and another 30% seemed to eschew such labels altogether and instead called themselves independent. It should also be noted that, despite the concern people have about more extreme political ideologies (e.g., Nazism, communism, anarchism), the present data suggest that the beliefs tend to be fairly rare. Readers may also find themselves pushing back and arguing that “no participants would ever call themselves a Nazi in a survey because they wouldn’t want to receive backlash for it.” It’s helpful to keep in mind that these surveys were anonymous and, as such, there would be no way for participants’ responses to be tied to them personally. Moreover, given how honest most participants are about other deeply personal issues (e.g., sex, religion), we do not believe that most participants would feel compelled to lie about their political leanings on these surveys.

In the following sections, participants completed a 46-item scale adapted from previous research (Laméris, 2015) that was designed to assess participants’ actual political ideology. Importantly, this scale avoided using labels, as it may be the case that some people may call themselves “liberal” or “conservative” without knowing what these terms mean or while simultaneously adopting views that are decidedly incompatible with the label they’ve used to describe themselves. Instead, the scale asks participants to indicate the degree to which they agreed or disagreed with all sorts of political issues ranging from minimum wage laws to the constitutionality of religious schools. Their answers were compiled and used to calculate scores on a number of important political dimensions, seen below.

In the above figure higher scores indicate being opposed to progressive social policies (e.g., legalizing gay marriage, transgender rights, etc.) Furries overwhelmingly scored more on the liberal / progressive side of the scale rather than the conservative side of the scale.

In the above figure higher scores indicate support for progressive economic policies (e.g., welfare, minimum wage laws, socialized medicine, etc.) Furries scored fairly high on the more progressive / socialist side of the scale than on the more conservative side of the scale.

In the above figure higher scores indicate support for greater economic regulation (e.g., laws governing what companies can and cannot do, etc.) while lower scores indicate greater support for unimpeded free markets. Furries were almost completely divided on this issue, with the bulk of furries scoring somewhere between the two extremes.

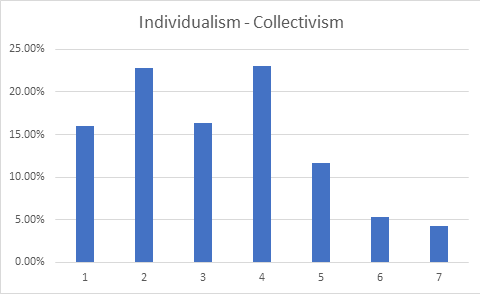

In the above figure higher scores indicate greater support for collectivist values (e.g., focusing on the group’s best interests rather than individual liberty) while lower scores indicate greater support for individualist focus (e.g., focusing on individual achievement and success over the needs of the group). Furries tended to lean far more toward individualism than collectivism, a finding quite common in Western countries.

In the above figure higher scores indicate greater support for state power (e.g., more laws, more government control of behaviour) while lower scores indicate greater support for small governments that have minimal power in peoples’ day-to-day lives. Furries tended to fall somewhere between the two extremes, with little preference for one position over the other.

In the above figure higher scores indicate greater support for egalitarian values (e.g., the idea that everyone should be treated as equals with equal value and equal opportunity) while lower scores indicate greater support for elitist beliefs (e.g., the belief that some people are inherently or socially superior to others or ought to be treated as such). Furries overwhelmingly fell on the side of egalitarianism.

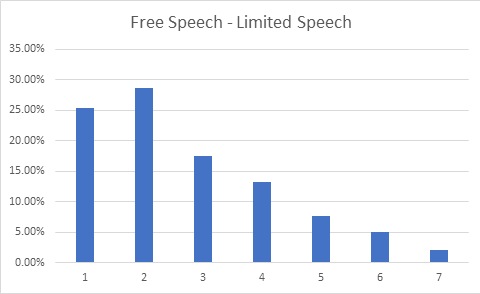

In the above figure higher scores indicate greater support for limitations on what a person should be allowed to say (e.g., barring controversial statements from being expressed publicly, stricter laws defining hate speech more broadly) while lower scores indicate greater support for unimpeded free speech (e.g., unimpeded rights to express any controversial opinion without censure or arrest). Despite many arguing that liberal-leaning, progressive groups tend to call for censure and limitation of free speech, furries were fairly strongly on the side of free speech.

Borrowing Fursona Elements:

In recent years, furries have begun asking whether the fandom, as a whole, supports or opposes the idea of one’s fursona being “inspired” by another person’s fursona. This could mean choosing a species that’s popular, being inspired to add cool or trendy elements to one’s fursona based on a popular furry, or simply adopting the aesthetics of another person’s fursona into your own. These are all contrasted against he idea of “creating one’s own fursona from scratch”—though some might argue that, short of creating an entirely new species from scratch, most fursona creation involves some degree of remixing or building upon existing content.

To assess these ideas, we asked furries a series of questions addressing whether or not they agreed, disagreed, or were largely neutral when it came to different aspects of taking inspiration for one’s fursona from others. The results were taken from a sample of furries attending Furry Fiesta 2019.

Most furries seemed to disagree with the idea that you shouldn’t base your fursona species on another person’s fursona. Or, to put it another way, most furries saw little problem with a person choosing their fursona species based on other furries’ fursona species. Whether based on famous furries / fursonas or simply basing it on the characters of your friends or local furry groups, it seems that furries are okay with the practice of being inspired to choose a fursona species based on other furries.

In a similar vein, most furries seemed to be okay with the idea of taking specific elements or aesthetics from another person’s fursona and incorporating them into one’s own fursona. This may be elements like accessories (e.g., oversized glasses, clothing) or colours and other design decisions.

Some have argued that certain species—in particular custom or created species (e.g., Dutch Angel Dragons)—suffer from being too popular or too commonly imitated. When asked how they felt about this idea in general, most furries seemed to disagree that they were annoyed by the practice. Or, to put it another way, most furries were okay with people choosing a fursona species that was popular or trendy.

While furries seem to be largely okay with the idea of drawing inspiration from another person’s fursona species in creating your own, there may be a limit. The above figure reveals that furries are fairly divided about whether or not someone should be upset when another person has created a fursona that’s similar to one’s own. It is worth asking, in future research, whether disagreement with this idea is based on the idea that people should instead feel flattered, or the practical realization that for some species (e.g., wolves, foxes) it may be difficult to create a fursona that is distinct from any existing fursonas of that species.

Speaking somewhat to the previous idea, most furries indicated that they would be flattered if they discovered that someone had borrowed elements of their fursona when creating their own fursona.

Finally, the above figure indicates that while furries tend to be fairly positive about the idea of borrowing elements of others’ fursonas in the creation of their own, most furries indicate that they, themselves have not engaged in this activity.

Anthropomorphization of Non-Human Animals:

Furries are defined as people who define themselves in part by their interest in media featuring anthropomorphized animal characters. It is worth asking, however, whether furries’ interest in anthropomorphizing non-human things is limited to animals. To this end, we asked furries at Furry Fiesta 2019 to indicate the extent to which they, themselves, tended to anthropomorphize various things.

The above findings reveal that, in-line with the definition of furries, non-human animals (pets, wild animals, and domestic animals) were the most commonly anthropomorphized non-human things. However, it should be noted that furries also tended to anthropomorphize other non-human things as well, including non-player characters in video games, the planet itself, and machines (e.g., computers, vehicles). That said, anthropomorphizing occurred most frequently for animals, and the tendency to anthropomorphize is not unique to humans, with other research suggesting that humans in general have a tendency to anthropomorphize their machines or nature—especially when they’re lonely.

Speaking to this latter point in particular, we also assessed the extent to which furries experienced bullying in their youth. We found evidence for the above model, which suggests that furries who were more bullied in their childhood were more likely to anthropomorphize non-human animals. These same folks were also more likely to see themselves as belonging to a common group with animals and to incorporate non-human animals into their sense of self. Taken together, this model might suggest at least one possible—and somewhat sad—pathway into an interest in anthropomorphism, one that coincides with some of our own findings on bullying (see 10.3). In short, furries who were more bullied may have found themselves turning to fantasy, or turning away from people, as a possible way to cope. This, in turn, may have led to a greater tendency to identify more strongly with anthropomorphized animal characters and to feel a greater sense of connection to animals in general. Future research will aim at more thoroughly testing this idea.

Bullying:

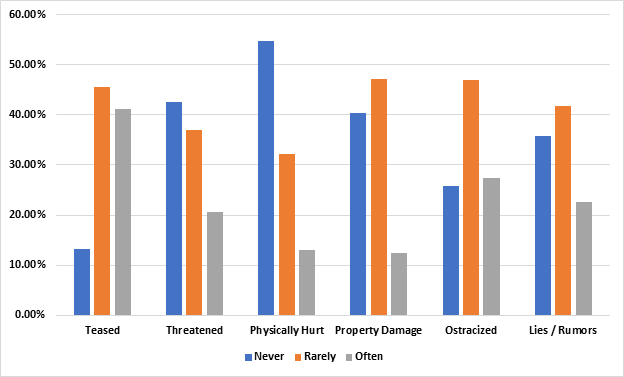

In a study of participants attending Furry Fiesta 2019, we asked furries to indicate the relative frequency with which they experienced different types of bullying, rather than simply indicating whether they had or had not been bullied in the past.

As the above figure indicates, most furries experienced at least rare teasing, ostracism, and the spreading of lies and rumors about them in their life. It was also common for furries to experience at least rare instances of property damage. More than half of furries indicated they had experienced at least rare threats, and nearly half of furries experienced at last rare instances of physical bullying. Taken together, these data suggest that most furries have been bullied and that this bullying primarily manifests in social ways (e.g., teasing, ostracism). Experiencing occasional bouts of physical harm or property damage, while rarer, is nevertheless fairly common among furries.

Donations to Animal-Related Charities:

In addition to advocating for animal rights and holding beliefs in support for animal rights, furries also have a tendency to regularly act in support of animal rights. In a 2019 study of Furry Fiesta attendees, participants were asked to estimate the amount they had contributed to animal-related charities. More than 60% of furries indicated that they had donated to animal-themed charities, with nearly a third indicated that they had donated more than $100 to animal charities. It is also worth noting that furry conventions—which most furries attend (see 2.12), nearly always support an animal-themed charity and afford furries numerous opportunities to donate while emphasizing the fandom’s norms of valuing charitable behavior toward animals.

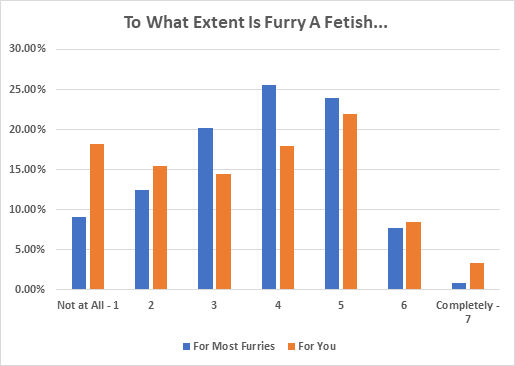

Furry as Fetish:

Largely replicating prior findings from Anthrocon 2018, a large online sample of furries from 2019 similarly found that furries are more likely to indicate that they expect furry to be a fetish for others than to personally consider furry to be a fetish for themselves. That said, for approximately 10% of furries, it would probably be correct to label furry as being primarily a fetish for them.

In the same study, we also asked participants to list any other kinks or fetishes they may have had, furry or otherwise. The result was a list of 827 unique responses, which were condensed into more than 300 separate categories. The most common kinks and fetishes are reported below, along with the proportion of people who indicated that interest, specifically among those who wrote at least one interest.

| Popularity | Kink/Fetish | % of Sample |

| 1 | BDSM | 39.2 |

| 2 | Power (Dom/Sub) | 16.0 |

| 3 | Transformation/Shapeshift | 14.3 |

| 4 | Watersports | 11.9 |

| 5 | Vore | 11.0 |

| 6 | Toys | 9.6 |

| 7 | Fursuit | 8.8 |

| 8 | Paws | 8.2 |

| 9 | ABDL/Babyfur/Cubfur | 8.1 |

| 10 | Feet/Shoes | 8.0 |

| 11 | Impregnation/Breeding | 7.5 |

| 12 | Inflation/Expansion | 7.4 |

| 13 | Macro/Micro/Sizeplay | 7.1 |

| 14 | Latex | 7.0 |

| 15 | Size Difference | 6.9 |

| 15 | Zoophilia | 6.9 |

It is worth noting several items in this list. In particular, the most common kink / fetish in the furry fandom, BDSM, is also among the most common observed in the general population. Moreover, despite the common misconception that furries are defined by a sexual attraction to animals or a sexual attraction to fursuits, both of these scored less than a 10% prevalence rate among people who self-reported having any kinks and fetishes—meaning that if one were to include the many folks who did not indicate having any kinks or fetishes, this number would be even lower. In short, the findings suggest that while many furries incorporate kinks and fetishes into their sexual lives, there is little evidence to suggest that it is a defining or necessary feature of the furry fandom. Moreover, among the fetishes most commonly associated with the furry fandom in the media, they make up a relatively small minority of the fandom.

Recent Comments