Fursonas are a nearly-universal aspect of the furry fandom. The vast majority of furries, either before entering the fandom or shortly upon entering it, create a fursona – a representation of themselves to the fandom. Such fursonas often involve choosing a species (or combination of species), a name, and a personality (however basic or complex) for this avatar. Much of the artwork within the furry fandom is dedicated to portraying furries’ fursonas, sometimes in badges to be worn at cons, other times through sketches or digital art that brings a person’s fursona to life through its representation in a particular situation, interacting with other fursonas, or simply creating a reference sheet to keep straight the details of one’s fursona.

Given the relative importance of fursonas, both to individual furries and to the artwork that plays a central role in the fandom, remarkably little research had been done investigating peoples’ relationship with their fursona and the psychological functions such fursonas serve.

This study also included pilot tests of several other items which, when tuned and adjusted for use in future research, may lead to further research on a number of previously unexplored topics within the fandom, including problematic aspects of the fandom, relationships within the fandom, and greymuzzles as a distinct subgroup within the fandom.

In total, approximately 175 questions were asked to 369 furries over the age of 18 in an online survey that ran from June to September of 2013. Given the vast amount of data, we are presenting only a subset of the findings here. As always, if you have questions, would like to know more, have suggestions for other analyses, please contact us (see the link on the sidebar).

All data are presented here in aggregate (summarized) form, and there is absolutely NO identifying information in the data. Data were collected in the strictest of confidence and are anonymous: we are unable to trace responses back to the original participants. Any unique responses that were reported in open-ended formats are not reported here in order to protect the anonymity of participants.

For those interested in statistics, basic summary statistics and the out puts of various analyses are included, where possible, in the presentation of this summary (e.g., t-tests, ANOVAs, regressions, means). You do not need to understand the statistics in order for the summary to make sense – they are included for the sake of those who have a knack for stats and who want to know a little more about the technical side of our research.

Summary of Questions:

Demographics

Q1: Are the furries in this sample comparable in age to previous samples?

Q2: What is the biological furries in your sample (and are there transgender individuals)?

Q3: Where do the furries in your online samples come from?

Q4: What about subgroups in your sample? (e.g., bronies, therians, greymuzzles)

Q5: Are there differences between greymuzzles and other furries?

Q6: Do furries identify with the fandom, the people in it, or with their fursona species?

Q7: Do furries meet relationship partners through the fandom?

Fursonas

Q8: Do furries only have one fursona?

Q9: Where do fursonas come from?

Q10: How similar are furries to their fursonas?

Q11: What do fursonas represent for furries?

Q12: Do fursona species affect how furries get along with each other?

Q13: Does it matter if furries are similar to their fursonas?

Role-playing

Q14: What are the most common role-playing activities among furries?

Q15: Is there a relationship between being a furry and role-playing?

Issues Within the Fandom

Q16: According to furries, what are the biggest problems/issues within the fandom?

Demographics

Q1: Are the furries in this sample comparable in age to previous samples?

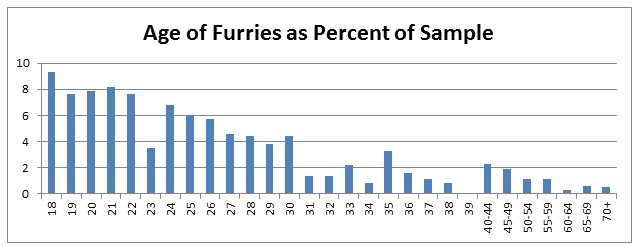

The average age of the furries in our sample is 26.6 years. This is comparable to samples from our prior research, which have had averages of 23-26 years. Comparable to our prior findings, we find that the vast majority of the fandom is under the age of 30 (approximately 80%), with approximately 1/3 of furries in our sample being between the ages of 18-21. Approximately 17.5% of furries were in their 30s, with 7.5% of furries reporting being in their 40s or older.

Put simply, these data support our prior findings, as well as the general intuition among most, that the furry fandom is quite heavily comprising adolescents and young adults.

Q2: What is the biological sex of furries in your sample (and are there transgender individuals)?

Also similar to our previous research, we find that the vast majority of furries tend to be biologically male (as seen in the table below). It is also worth noting that there is are a significant number of transgendered individuals within the furry fandom and, like with transgendered individuals in the broader population, MTF transgender individuals are approximately three times more prevalent than FTM transgender individuals (DSM-IV, p.535). It is also worth noting that this prevalence is at least 18 times the prevalence of the general population at a conservative estimate, and may be more than 100 times more prevalent, depending on which figures of the general population are being used (e.g., Olyslager & Conway, 2007; Wilson, Sharp, & Carr, 1999).

Regardless, these data should be taken with a grain of salt: given the rarity (relatively speaking) of transgender individuals, it is difficult to make broad, sweeping claims about its relative frequency within the furry fandom. Nonetheless, initial data seem to suggest, at very least, that it is much higher among the furry fandom than in the general population.

|

Male |

83.7% |

|

Female |

13.0% |

|

MTF Transgender |

1.8% |

|

FTM Transgender |

0.7% |

|

Other |

0.8% |

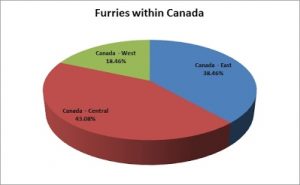

Q3: Where do the furries in your online samples come from?

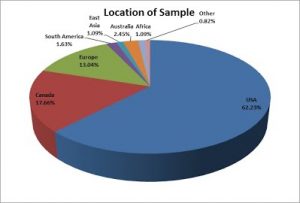

In line with our previous research, we found that the majority of participants in this study were from the United States, with a significant number from both Canada and Europe. Like in our previous findings, this is likely a by-product of our survey being in English, which would disproportionately over-represent English-speaking countries within the sample.

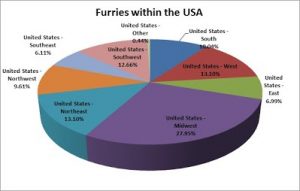

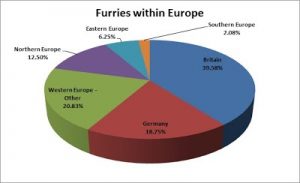

Additionally, however, we were interested in sub-dividing the location of participants further. As such, we asked furries to identify, if they were from the United States, the particular part of the United States they were from and, if they were not from the United States, what country they were from (or, if they were from Canada, what part of Canada they were from).

In future research we are hoping to disperse our surveys in additional language and through as many different online channels as possible to better capture the global nature of the furry fandom.

Q4: What about subgroups in your sample? (e.g., bronies, therians, greymuzzles)

We asked our sample to indicate whether or not they self-identified with any of the identities below. It is important to note that we did NOT provide definitions or descriptions of any of the labels, instead allowing participants to decide for themselves whether the label applied. While it may be the case, for example, that a person’s beliefs are largely in-line with those of the Therian community, if they have not heard the term “Therian”, chances are that the participant is not a member of the Therian community (and, as such, their identity is not impacted by the label of “Therian” or the norms of the Therian community).

| Are you a… | % of Sample that said “Yes” |

| Furry | 96.7 |

| Therian | 10.8 |

| Otherkin | 4.6 |

| Lycanthrope | 3.0 |

| Brony | 16.5 |

| Greymuzzle | 9.2 |

The data collected are generally in-line with our prior findings about subgroups within the furry fandom, although therians and bronies tended to be slightly less represented in this sample than in previous findings.

Q5: Are there differences between greymuzzles and other furries?

One subgroup within the furry fandom of particular interest to the IARP is the group of furries identifying themselves as “greymuzzles”. While there is no “official” cutoff for when one can identify themselves as a greymuzzle, they tend to be furries who have either been in the fandom for a significant amount of time (e.g. more than a decade) and, generally speaking, are furries that are significantly older than the average furry (e.g. furries into their 40s and 50s).

In the present study, participants who identified themselves as greymuzzles were, on average, 42.2 years old. They report having had furry interests for longer than the average non-greymuzzle furry (21.8 years vs. 10.7 years, p < .001) and having been in the fandom for longer (12.3 years vs. 6.2 years, p <.001). Interestingly, greymuzzles were also more likely to state that there was a longer “gap” between the time they had developed furry interests and the time they found the fandom itself (9.5 years v. 4.6 years, p =.002). There are two plausible explanations for this: on the one hand, the fandom was a different place fifteen or twenty years ago, and without the internet it was much harder to discover the furry fandom (which means it would take longer before finally “stumbling” upon the community). Alternatively, it’s possible that greymuzzles are people who have had an interest in the furry activities for a greater part of their life (e.g. since childhood, as opposed to since their teenage years), suggesting it is a lifelong interest (which would also explain why they remain in the fandom well into their 30s and 40s). Future research will hopefully allow us to test which of these theories best explains these findings.

Greymuzzles were also significantly more likely to self-identify as therians than non-greymuzzle furries (32% vs. 9%, p = .007).

The only other significant difference between greymuzzles and non-greymuzzle furries is in terms of roleplaying: greymuzzles reported less interest in roleplaying activities than non-greymuzzles (p = .028). This may be a product of changes in the fandom over time, with chatrooms and the rise of online roleplaying games such as Second Life potentially appealing to younger furries.

It is worth noting, however, that despite these differences, greymuzzles did not significantly differ from other furries with regard to the extent that they self-identified themselves as furry or identified with the furry community, nor did they differ in their identification with their fursona species, their beliefs that they were not completely human (surprising, given that greymuzzles were more likely to self-identify as therians themselves, which may suggest that many younger furries subscribe to Therian beliefs without knowing it), or in their overall well-being.

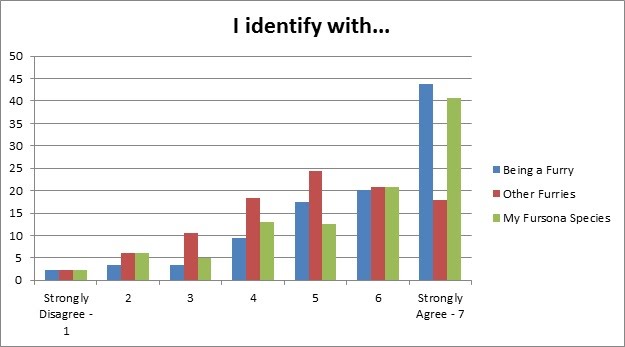

Q6: Do furries identify with the fandom, the people in it, or with their fursona species?

We asked participants to indicate the extent to which they identified with being a furry, the extent to which they identified WITH other furries, and the extent to which they identified with their fursona species. As you can see from the table below, participants considered these to be three separate, if related, issues. In general, participants were most willing to agree that they identified as a furry (M = 5.72, ps <.02). Participants agreed least of all that they identified with other furries in the fandom (M = 4.90, ps < .001). Participants’ identification with their fursona species was between the two (M = 5.52).

Put another way, participants identified, first and foremost, with the label of “furry”, then with the species chosen in their fursona, and finally with the others in the furry fandom. Even though other furries were less identified with than the overall label of furry or with their chosen fursona species, this average is well above the midpoint of the scale, suggesting that many furries identify quite strongly with other furries in the fandom.

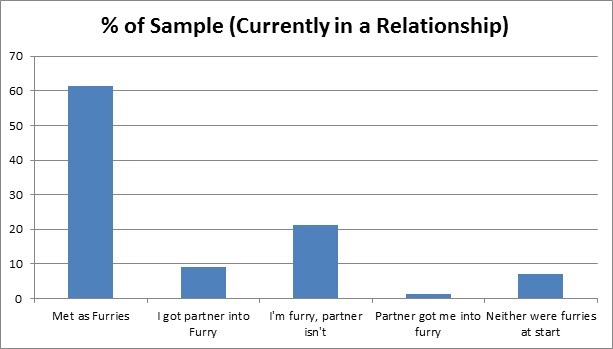

Given the importance of the furry fandom as a source of social interaction for many furries, we investigated whether furries who were currently in relationships met their partners in the fandom, brought non-furry partners into the furry fandom, or were brought into the fandom as a result of their partner. The data below clearly illustrate the fact that a majority of furries in relationships met their significant other through the fandom. It was also somewhat common for furries to have non-furry partners who were not a part of the fandom (about 20% of furries). Far more rare were people who introduced their partner to the furry fandom, or who got into the fandom along with their non-furry partner.

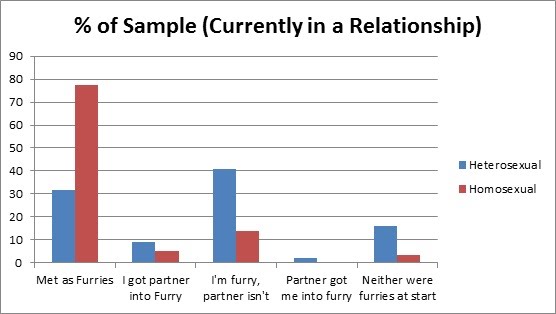

As the figure below makes clear, however, these trends differ, depending on whether or whether or not participants self-identified as homosexual. As you can see from the figure below, homosexual furries are much more likely to find their current relationship partner in the fandom, whereas for straight furries they were actually more likely to find their partner outside of the fandom (and are more likely to have a partner who is not a furry). This makes intuitive sense: given the prevalence of males in the furry fandom, it should be easier for homosexual furries to find same-sex partners within the furry fandom than for heterosexual furries to find opposite-sex partners within the fandom.

Fursonas

Q8: Do furries only have one fursona?

Like in past research, we asked furries to indicate the number of fursonas they have had over their entire life. Based on prior feedback from furries, however, we also included a second question, asking furries to indicate not only how many furries they have had, but to also indicate the number of fursonas they currently have.

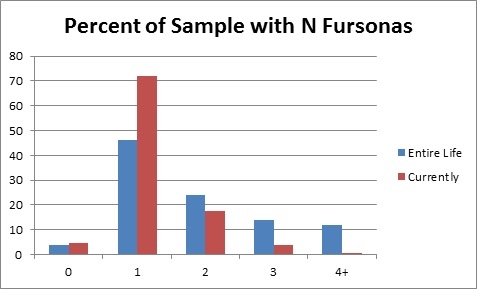

As you can see from the figure below, while 1 fursona is the most common number of fursonas to have had over the course of one’s life, about half of furries report having had more than one fursona, suggesting that at least a significant portion of the furry fandom has changed their fursona at some point in their life. Future research will hopefully shed some light on the reasons that furries change their fursonas.

Also of interest, nearly three-quarters of all participants indicated that they currently have only one fursona. That said, almost a quarter of furries say just the opposite, that they currently have more than one fursona. It would be interesting, in future research, to determine the function of having multiple fursonas (e.g. for self-expression, in different contexts, to represent different genders / orientations, etc…).

Q9: Where do fursonas come from?

Relatively little is known about the process of fursona creation. For example, while many furries describe their choice of fursona species as inspired by a particular show, character, story, traditional legend, or exemplar of a species (e.g. a famous animal, a pet, etc…), many furries have also vehemently stated that their fursona came from within them, in an act of creation (as opposed to “merely copying” a character from a show). Indeed, one of the major criticisms of the brony subculture is the belief that OCs (“original characters”) are derivative of the source material and lack the “genuineness” of a self-inspired, self-created fursona.

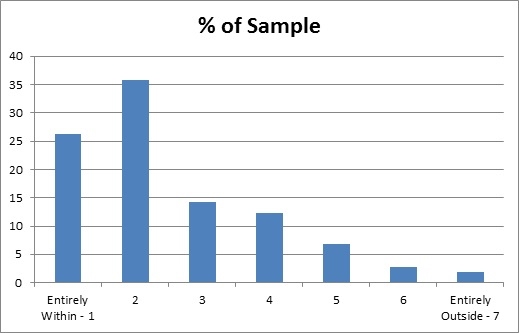

To investigate the source of fursonas, we asked furries to indicate, on a 7-point scale, the extent to which they felt that their fursonas came from entirely within themselves, from entirely outside themselves, or somewhere in the middle. As you can see from the figure below. First off, it’s apparent that for most furries, fursonas come primarily from within themselves (M = 2.53). That said, however, it should also be noted that only about 25% of furries said that their fursona came from entirely within themselves. In other words, while most furries would agree that their fursonas came primarily from within themselves, many would also agree that there was, to at least some extent, some outside influence on their fursona.

We are also greatly interested in the furries at the other end of the spectrum, for whom fursona choice came entirely from something outside of themselves. Whether this means that they felt they had no choice in how their fursona manifested itself, or whether they simply chose a fursona based on a show, story, or character that they admired, it would be interesting to know whether such fursonas differ in the extent to which they are used for self-expressive purposes.

It is also worth noting that, in a subsequent analysis, it was found that the more a person’s fursona was said to come from an outside source, the more likely that person was to experience decreased well-being (B = -.148, p = .014), decreased self-esteem (B = -.155, p = .010), and decreased overall sense of having a coherent and developed sense of self (B = -.135, p = .025). This association does not mean, of course, that having a fursona that did not come from within oneself somehow caused decreased well-being, but only suggests that there is an association between these two factors (which can either be explained by a third variable they are both related to, or perhaps the reverse: that furries who are low in well-being tend to base their fursonas on external, not internal, inspiration).

Q10: How similar are furries to their fursonas?

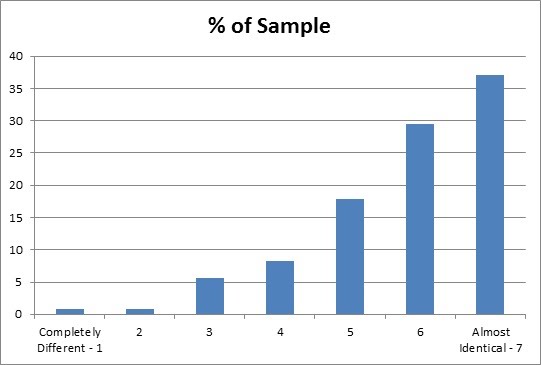

In a similar, but distinct vein to Q10, we asked furries to indicate the extent to which the personality of their fursona was similar or different from their own. We asked them to indicate the extent of this similarity on a 7-point scale ranging from “completely different” to “almost identical”.

As you can see from the scale below, most furries tended to have fursonas that were comparable in personality to their own. That said, only about 35% of furries said that their fursona’s personality was almost identical to their own; many furries acknowledged at least some differences between their fursona’s personality and their own.

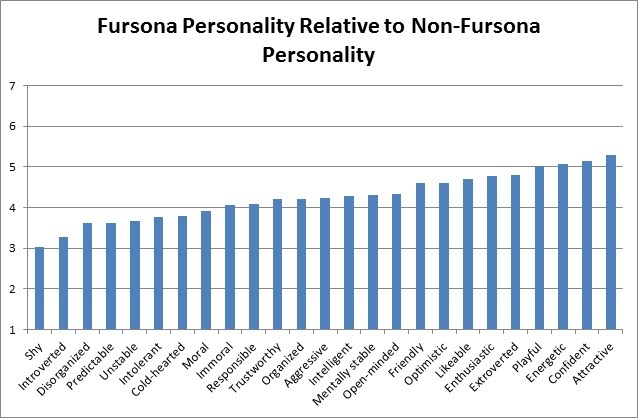

To further test perceptions of similarity, we asked furries to indicate, for a number of different personality traits, the extent to which their fursona was like them (1 – Less ______ than me, 4 – About as ______- as me, 7 – More __________ than me). In the scale below, the bars closest to “4” indicate the personality traits that furries saw their fursonas as being comparable to themselves on. Bars lower than “4” mean traits that they feel their fursona has less of than they do. Bars higher than 4 indicate traits that fursonas are thought to have more of than themselves.

As you can see from the figure, fursonas were quite comparable to non-fursona selves on a number of traits (e.g. morality, responsibility, trustworthiness). The traits that fursonas were lower on tended to be traits that are frowned upon, or which have a negative connotation (e.g. shy, disorganized, predictable, unstable). In contrast, many of the traits people consider to be quite positive are traits that fursonas score higher than furries’ non-fursona selves on (e.g. attractive, confident, playful, enthusiastic, friendly). This preliminary evidence suggests that fursonas may, at least as part of their function, represent an “idealized” version of oneself.

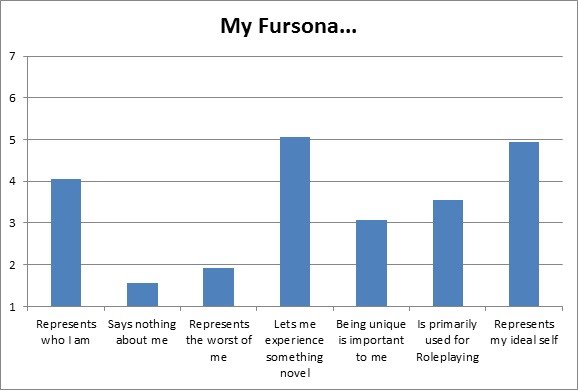

Q11: What do fursonas represent for furries?

We asked furries a number of questions about the potential function of their fursonas on 7-point scales, indicating the extent to which they agreed that their fursona fulfilled that purpose for them (1 – Strongly Disagree, 7 – Strongly Agree).

As you can see from the able below, most furries agree that fursonas have two important functions: they allow the person to experience something novel, and they tend to represent an idealized version of themselves (e.g. my fursona is like me, but a more “enthusiastic” or “outgoing” me).

Furries were more ambivalent about whether or not their fursonas represent who they currently were; many agreed with this point somewhat, likely due to the fact that fursonas, while “based off of” who a person currently is, also come to represent an idealized version of the self as well.

While there was a tendency for furries to disagree slightly with fursonas’ use for roleplaying, there were some furries who did agree that their fursona existed primarily for the purpose of roleplaying.

Being unique wasn’t a prerequisite for many furries, who suggested that it wasn’t that important for their fursona to be particularly unique.

Finally, most furries strongly disagreed that their fursona represented something negative about themselves, or that their fursona had nothing to do with them. We’ll follow up more with this point in Question 15.

In sum, these data suggest that fursonas may serve a number of different funtions for different people, but, in general, many furries agree, at least somewhat, with the idea that their fursonas represent a somewhat idealized version of themselves.

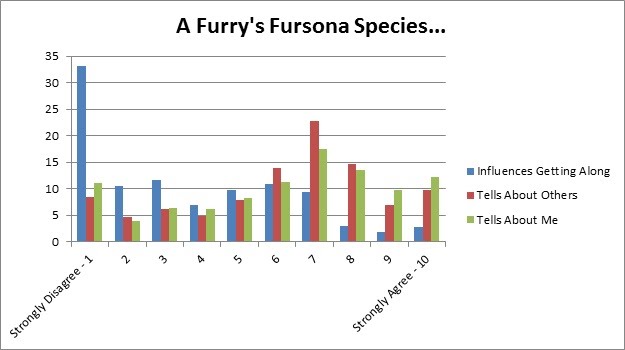

Q12: Do fursona species affect how furries get along with each other?

Similar to prior research, we asked furries not only whether their fursonas said something meaningful about themselves, but also to indicate the extent to which fursonas could tell them something meaningful about others and even the extent to which it would influence how they interacted with others.

Looking at the green bars in the figure below, it’s apparent that many furries agree that their fursona species says at least something about themselves (M = 6.12) and, similarly, says something about others (M = 6.15). Indeed, the more furries believed a fursona said something about themselves, the more they felt it also said something important about others (r2 = .74, p < .001). Interestingly, however, furries were far less likely to say that a person’s fursona species would influence how well they got along with them (M = 3.65). Despite that, however, the more a person believed their fursonas said something about themselves, the more likely they were to say that someone else’s fursona would influence how well they got along with them (r2 = .44, p < .001).

Q13: Does it matter if furries are similar to their fursonas?

We indicated earlier (Q10) that furries differ in the extent to which they see themselves as similar to their fursonas. In Q11, we learned that, for many furries, their fursonas represent their idealized selves.

We are interested in the implications of the above two statements: if furries believe that their fursonas represent their idealized selves, is it important whether or not furries see themselves as “just like their fursonas” or as being very different from their fursonas? Currently, we believe that fursonas, for many furries, represent an idealized self that furries may be striving to become more like. For example, if you are a particularly shy person, having an outgoing, extraverted fursona may give you an opportunity to “try out” being an extraverted person within a relatively safe and supportive community. As such, to the extent that furries spend time as this idealized self, it may improve their overall self-esteem and well-being, given that spending time as their idealized selves may help them to become like their idealized selves.

If, however, furries have a particularly negative view of themselves, or pick idealized fursonas that differ too significantly from their current self, it may lead to a significant discrepancy that leaves furries feeling discouraged or upset with themselves for not being more like their fursona.

When we look at the data, we find that they support this hypothesis; in general, when furries stated that their fursonas represented their ideal selves AND when they said that they felt their fursonas were quite different from who they currently were, this led to greater frustration about this difference (B = .487, p = .003) and, what’s more, this combination of factors was associated with a decrease in self-esteem (B = -.434, p = .025) and marginally associated with decreased overall well-being (B = -.335, p = .078).

Put another way, the more a person’s fursona represents their ideal self and the closer they feel to that idealized fursona, the better off they tend to be with regard to overall well-being, life satisfaction, and self-esteem. The fact that having a fursona that represents one’s ideal self is ALSO associated positively with roleplaying activities (B = .167, p =.005) suggests there may be some truth to the idea that a fursona representing one’s ideal self is being used to “roleplay” the kind of person furries may want to be like, especially considering these roleplaying activities, in turn, are associated with the feeling that one has become more like their fursona over time (B = .275, p <.001).

In general, regardless of whether or not furries’ fursonas represented their ideal selves, choosing a fursona that differed significantly from oneself was associated strongly with reduced well-being (B = -.358, p <.001), reduced life satisfaction (B = -.455, p < .001), and greater frustration (B= -.444, p <.001).

It seems to be the case that a fursona, far from being trivial, can be deeply meaningful for furries. In particular, the combination of what the fursona represents for the individual furry, coupled with the perceived relationship they have with their fursona (i.e., whether or not they feel that they and their fursona are similar) is significantly associated with their well-being and their overall positive sense of self. This data is only correlational, so it remains for future research to determine whether discrepancies between the self and one’s fursona cause these decreases in well-being or whether they are a symptom of pre-existing low self-esteem and poor well-being. Nonetheless, this research suggests that fursonas may play an important role, whether as a mechanism supporting, or an indicator of an existing, problem (or as a mechanism contributing to, or indicator of, a healthy sense of self).

Role-Playing

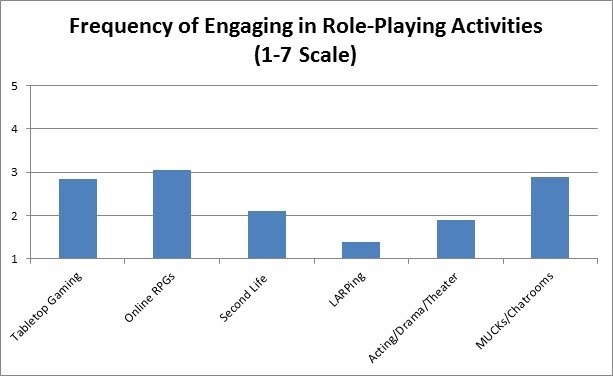

Q14: What are the most common role-playing activities among furries?

We asked furries to indicate, on a 7-point scale (1 – Not at all, 7 – All the time) the frequency with which they engaged in various role-playing activities. As you can see from the table below, no one activity distanced itself from the others as being a universally engaged in activity. That said, it did seem to be the case that furries somewhat regularly engage in tabletop gaming, online RPGs, and role-playing in MUCKs and chatrooms. Future work may help to determine what factors may predict certain types of roleplaying activities, or whether there are better roleplaying activities that furries more regularly engage in.

Q15: Is there a relationship between being a furry and role-playing?

While there seemed to be little consensus regarding what types of roleplaying activities were popular among furries, there was evidence to suggest that there was at least some relationship between furries and roleplaying more generally.

Specifically, the data suggest that the more a person identifies with being a furry, the more they engage in roleplaying activities as a whole (B = .212, p <.001). Additionally, the more a person considered themselves to be a furry, the more likely they were to become easily transported into the world of a fictional narrative (B = .243, p <.001).

Taken together, and coupled with the findings from Q13, the data may suggest that furries, as a group who more readily allow themselves to become immersed in fiction, may be particularly likely to be influenced by time spent taking on the roles of their fursonas, which, for many, represent their ideal selves. This is likely to be a topic of further research in the upcoming year.

Issues Within the Fandom

Q16: According to furries, what are the biggest problems/issues within the fandom?

In the final section of the survey, we asked furries to indicate whether or not there was anything about the furry fandom that they disliked, found problematic, or would change if they could. This open-ended data was compiled, coded, and organized into the following list, which provides one of the first comprehensive, systematic looks into the issues that are prominent in the furry fandom today and the concerns that furries have about the fandom. They are organized based on the frequency with which each topic was raised:

- The fandom is too sexual, and too openly so (e.g., behaviour / porn in public settings).

- The fandom has a negative public image (e.g., people associate furries with sex or deviant behaviour).

- The fandom includes / is too tolerant of deviant fetishes.

- There is too much drama / conflict within the fandom (e.g., between subgroups, or within local furry groups).

- There are problematic furs within the community (e.g., furries who cause problems within local groups).

- Certain subgroups within the fandom are a problem (e.g., bronies, therians, babyfurs, nazifurs)

- The fandom is too restrictive (e.g., it tries to suppress sexuality or exclude others).

- Members of the fandom are immature / childish.

- Members of the fandom can be socially awkward and make others feel uncomfortable.

- There is a real problem defining what furry is and is not.

- The furry fandom is too open, and allows in too many people that it should not be associating itself with.

- There is a problem with stereotyping within the furry fandom (e.g. groups stereotyping other groups within the fandom).

- There is a sense of entitlement within the fandom (e.g. people demanding unreasonable things of artists).

- The fandom is becoming too mainstream, and this is diluting the content of the fandom.

- There are significant gender issues within the fandom (e.g. the number of, and treatment of, women within the fandom).

- Some people take the fandom too seriously.

- Fursuiters are a problem in the fandom (specifically fursuiters doing inappropriate things).

- There is a lot of bad art/artists within the fandom.

- Art in the fandom is too expensive.

Recent Comments