Minorities Within a Minority, Face Recognition, and Furry Pornography

In February, the IARP attended Furry Fiesta for the fifth consecutive year. In these past five years, Furry Fiesta has become a “testing ground” for the IARP’s newest ideas and methodologies – testing the practicality of running particular studies in the field and getting a set of preliminary data which allow refinement or rethinking of our research questions. This year was no different: the IARP launched several new lines of research at Furry Fiesta, which included a new computer-based reaction time and image-rating study, a new line of focus group research, and several new lines of inquiry in our tried-and-tested surveys.

This write-up represents a brief summary of the data we collected at Furry Fiesta 2015. As with all of the IARP’s write-ups, we endeavor to find a balance somewhere in the middle ground between writing up a small, overly simplistic point-form list of conclusions and flooding the reader with hundreds of pages of statistics. While there are certainly many more findings than are presented here, the present results were chosen because they are the most interesting to furries, have the most potential to lead to future research, or because they were the most surprising to us.

As always, if you have questions, concerns, or criticisms about the presented findings, or would like us to run an analysis to satisfy your own curiosity, please e-mail Dr. Courtney “Nuka” Plante at courtney.plante@furscience.com.

Methods: What did you actually do?

The data presented here represent a compilation of three separate studies that were simultaneously conducted at Furry Fiesta. In all studies, all participants were over the age of 18, as required by our ethics review board, and all participants’ information was contributed anonymously and confidentially.

In the first study, 245 attendees of Furry Fiesta 2015 completed a short pencil-and-paper survey handed out to them during the convention by research assistants. Participants were recruited while standing in the registration line or at the researcher’s table outside of the Dealer’s Den. The survey consisted of a number of questions ranging from simple demographic questions to questions about subjective age, felt closeness to one’s fursona, mood and well-being, disability, attitudes toward artists, and self and group perceptions.

In the second study, approximately twenty short, one-page surveys were handed out randomly to artists in the Dealer’s Den, of which one dozen were returned. This study asked artists about a variety of artist-specific issues. While this sample is small, it is a targeted sample, and represents a proof-of-concept for a similar, but much larger-scale project the IARP hopes to conduct at Anthrocon 2015, looking to study artists within the fandom, a group who, to this point, remains relatively unstudied. Questions from this survey were designed to be compared with responses from previous studies, to allow us to compare artists’ perceptions of fans to actual fan responses.

The third study conducted at Furry Fiesta 2015 involved the use of a dual-purpose computerized study which aimed to compare furries to a non-furry sample of comparable age: college undergraduates. 120 undergraduates at Texas A&M University – Commerce completed the study online, while 74 furries attending Furry Fiesta completed the computerized study in-person at the convention. The study began by collecting demographic information, as well as basic attitudes and beliefs about participants. The first half of the study then involved participants evaluating a set of 100 images, which differed on a number of variables: whether they were furry or non-furry, whether they were “clean”, “nude”, “erotic”, or “explicit”, and whether they contained men, women, or both. For each image, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they would classify the image as “pornographic”, and were then asked to rate how arousing they personally felt toward the image. They were later asked to estimate how they thought furries and non-furries would rate the image.

In the second part of the study, participants were presented with a series of faces, half of which were shown from the first part of the study, the other half of which were novel. Participants had to answer whether or not they recognized the face from earlier in the study or not. This task was designed to test whether or not furries were better at recognizing furry faces and fursuits better than non-furry participants.

Results: Get to the Data!

The results of our findings are presented with the aim of making them as accessible as possible to everyone reading. As such, we display two forms of our results: one geared toward an audience with little to no statistical background, who want a simple, concise answer to the research question, and a second targeted toward readers who are more stats-savvy, which include the results of t-tests, ANOVAs, and multiple regression analyses conducted using the statistical program SPSS.

Subjective Age: How old do you feel?

1. Do furries feel younger or older than they actually are?

Short answer: In general, furries are more likely to report feeling younger than their actual age. As furries get older (e.g., over the age of 30), they are far more likely to do so, and to do so to a far greater extent.

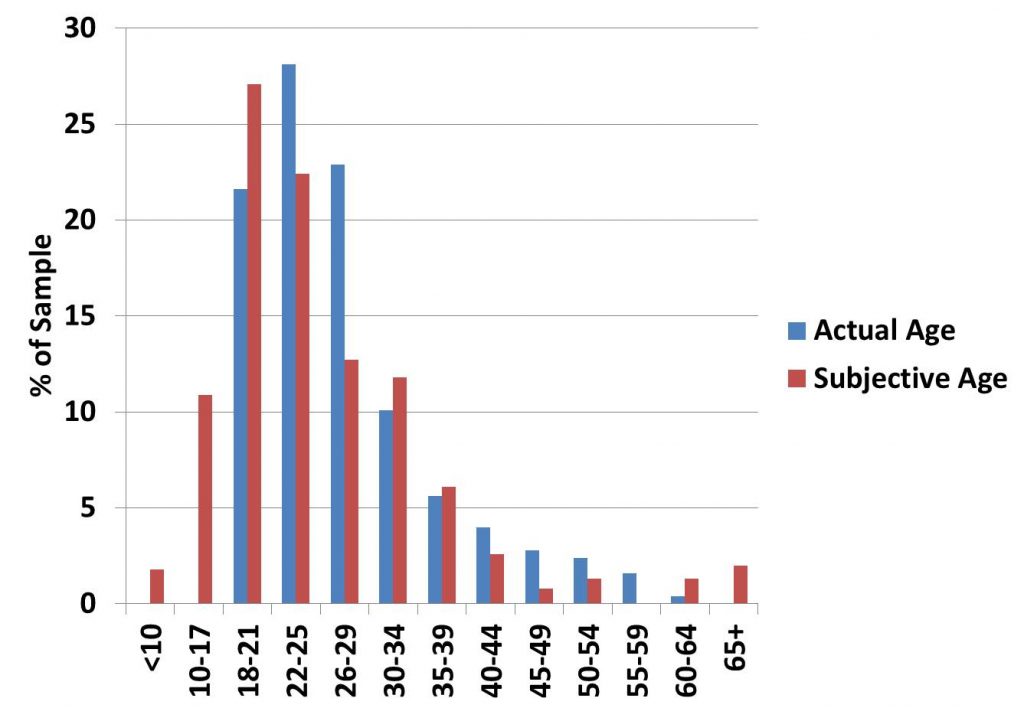

Long answer: As illustrated in the image above, the “peak” of subjective (felt) age is younger than that of objective (actual) age. Additionally, 10% to 15% of furries identified their felt age as being under the age of 18, while comparatively fewer identified a subjective age older than 40. A repeated-measures t-test confirmed that the mean actual age of furries (M=28.00 years, SD = 8.92) was significantly higher than the mean subjective age of the same furries (M=25.27 years, SD = 9.90; t(227) = 4.13, p<.001). The average furry felt about 6.89% younger than their actual age.

Long answer: As illustrated in the image above, the “peak” of subjective (felt) age is younger than that of objective (actual) age. Additionally, 10% to 15% of furries identified their felt age as being under the age of 18, while comparatively fewer identified a subjective age older than 40. A repeated-measures t-test confirmed that the mean actual age of furries (M=28.00 years, SD = 8.92) was significantly higher than the mean subjective age of the same furries (M=25.27 years, SD = 9.90; t(227) = 4.13, p<.001). The average furry felt about 6.89% younger than their actual age.

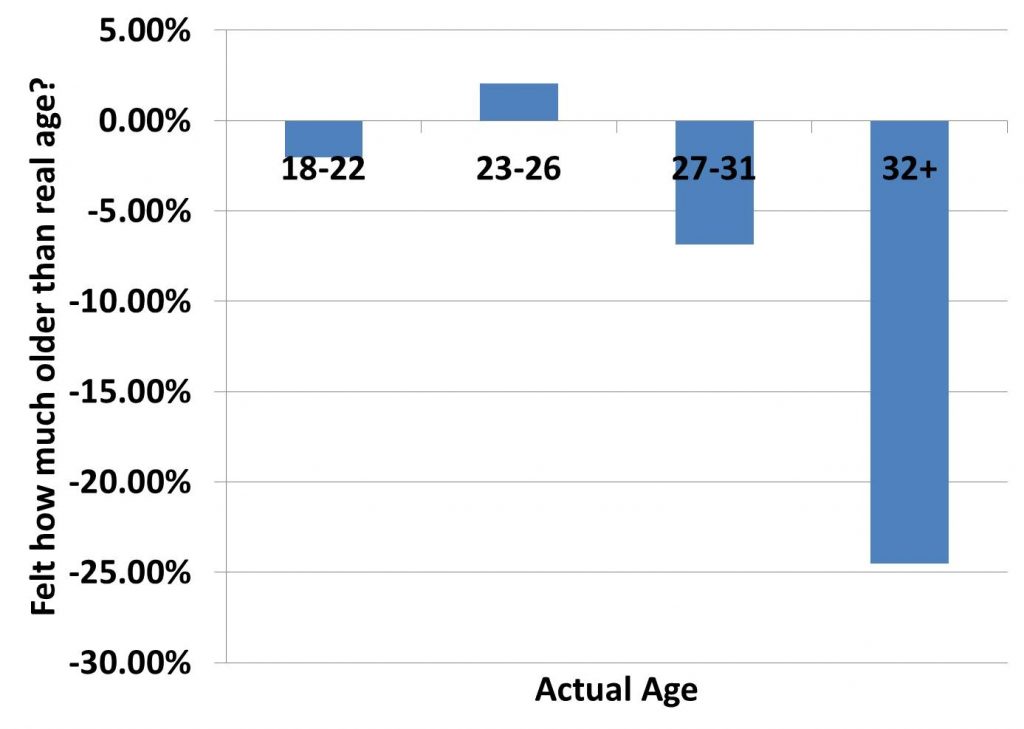

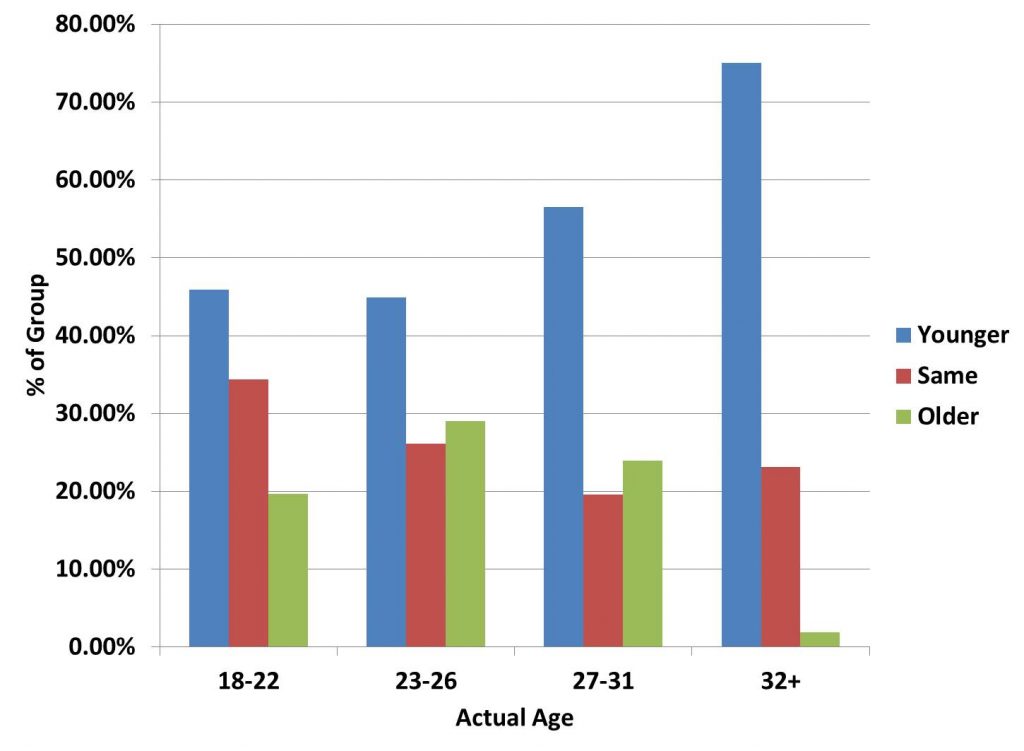

Next, we divided the sample into approximate quartiles by age, allowing us to test whether older or younger furries were more likely to feel younger than their actual selves. In the first figure above, we see that furries in the oldest quartile rated themselves, on average, 24.50% younger than their actual selves, as compared to furries in the other quartiles, who rated themselves between 6.85% younger and 2.07% older than their actual selves, on average, a difference that was statistically significant (F(3,224) = 6.79, p<.001). In the second figure above, we counted the percentage of members of each quartile who said they felt younger, the same age, or older than their actual selves. In accordance with the above findings, while all furries were more likely to say they felt younger than their actual selves (as compared to the same age or older), older furries were the most likely to do so.

Next, we divided the sample into approximate quartiles by age, allowing us to test whether older or younger furries were more likely to feel younger than their actual selves. In the first figure above, we see that furries in the oldest quartile rated themselves, on average, 24.50% younger than their actual selves, as compared to furries in the other quartiles, who rated themselves between 6.85% younger and 2.07% older than their actual selves, on average, a difference that was statistically significant (F(3,224) = 6.79, p<.001). In the second figure above, we counted the percentage of members of each quartile who said they felt younger, the same age, or older than their actual selves. In accordance with the above findings, while all furries were more likely to say they felt younger than their actual selves (as compared to the same age or older), older furries were the most likely to do so.

2. Furries think they’re younger than they actually are. So what?

Short answer: Furries whose subjective age differs from their current age are more likely to have reduced self-esteem and are more likely to rely on their fursonas to represent more positive (presumably youthful) aspects of themselves. While we didn’t explicitly ask people about their fursona’s age, we believe that a person’s fursona may reflect their felt age (given past research showing that fursonas often represent idealized versions of a furry’s self), a hypothesis we will be testing in future research.

>

>

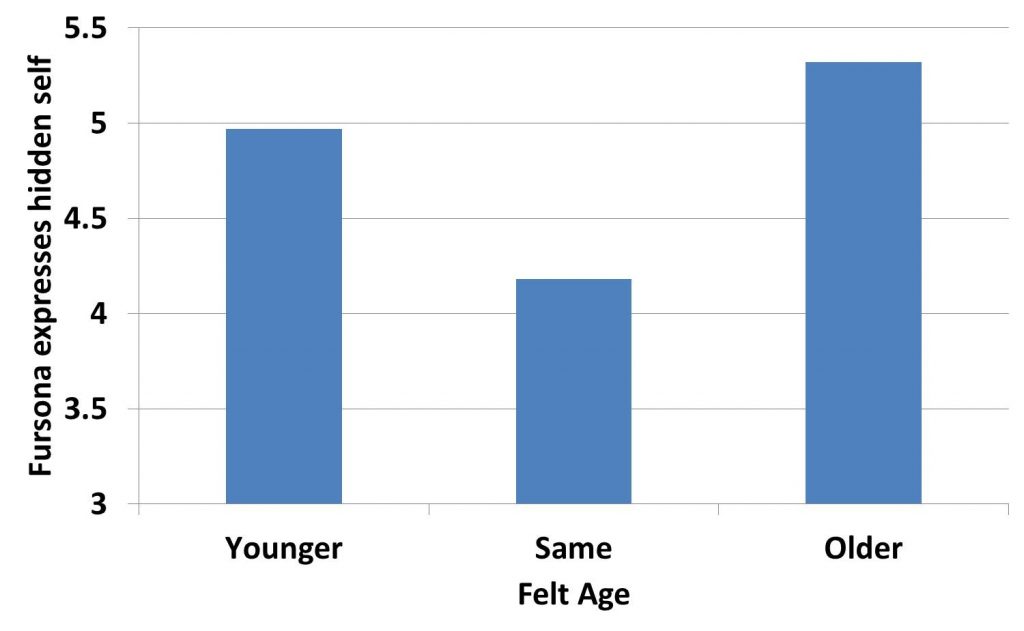

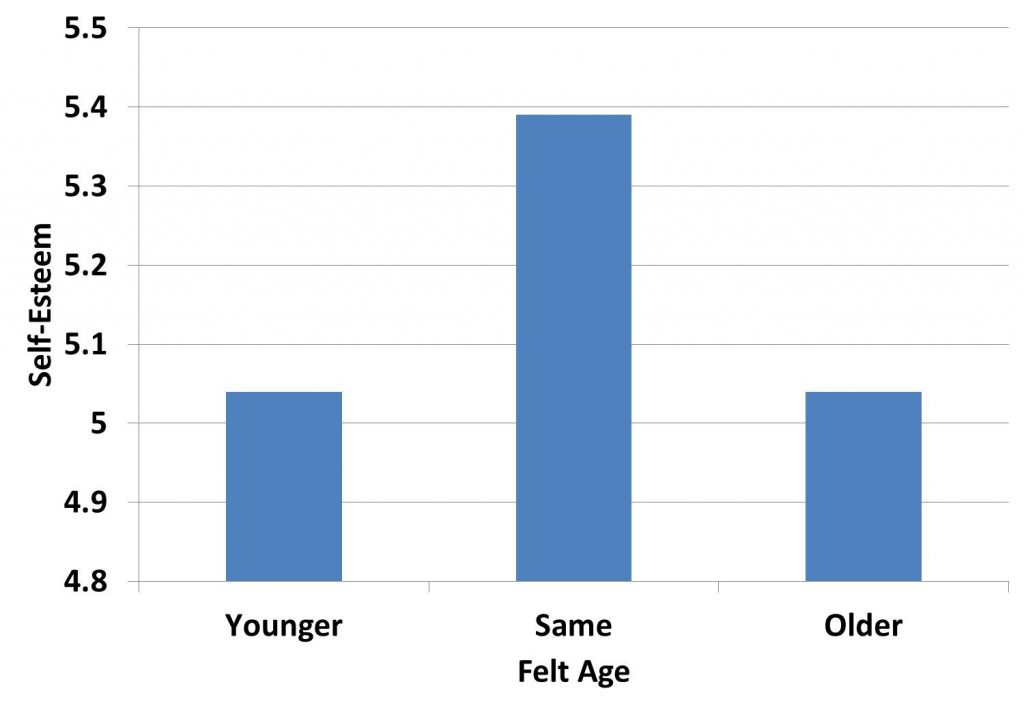

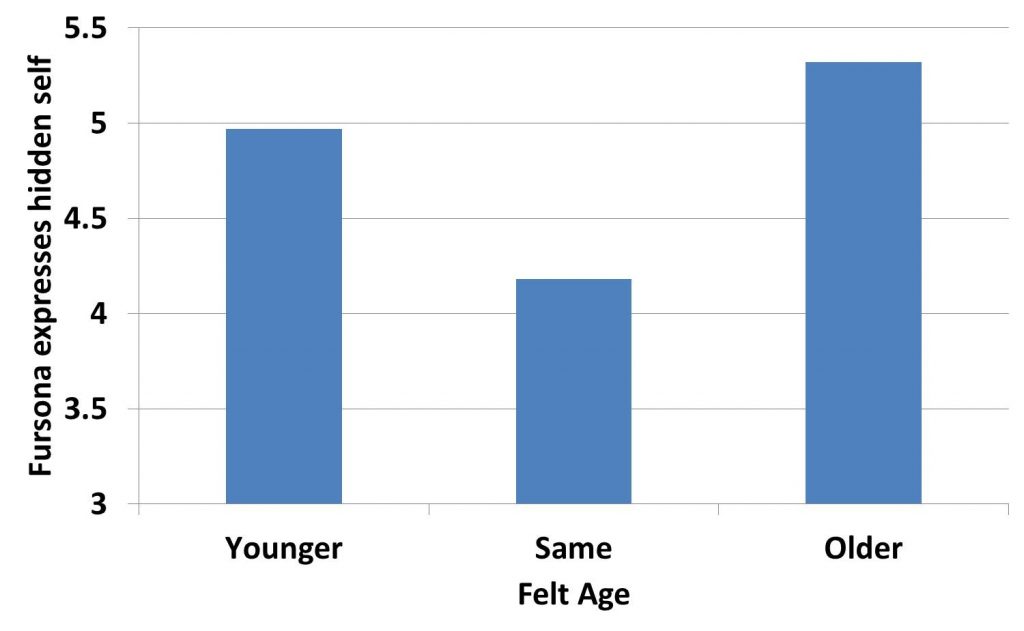

Long answer: As illustrated by the first figure, evidence suggests there is a relationship between a furry’s felt age and their self-esteem. In particular, furries whose felt age was the same as their actual age had the highest self-esteem, albeit marginally so, statistically speaking (F(2,224) = 2.81, p = .062). While one has to be cautious when interpreting correlations, as it is impossible to determine the direction of causation, it may be the case that furries with a higher self-esteem feel more content with who they are, whereas furries with a lower self-esteem feel a greater pressure to be different, whether older or younger. Other evidence may support this interpretation, as presented in the second and third figures above. In the second figure, furries whose felt age differed from their current age were also more likely to agree that their fursona allowed people to see a more genuine version of themselves (F(2,222) = 2.95, p = .054), while the third figure reveals that furries whose subjective age differs from their actual age were more likely to say that their fursona expressed a hidden aspect of themselves (F(2,221)=4.14, p = .017). All of these analyses were conducted while controlling for participants’ actual age, ruling out the possibility that actual age played a confounding role in these findings.

Prior IARP studies have shown that furries often create fursonas that represent idealized versions of themselves: fursonas are often more positive, enthusiastic, likable versions of themselves. It may be the case that subjective age reflects another aspect of this “ideal self” – insofar as furries feel dissatisfied with who they are, they create fursonas that are better versions of themselves and strive to become more like them. The present data suggest that this ideal self may include differing subjective age. In the future, we plan to further test these hypotheses by asking furries to indicate the approximate age of their fursonas, to see how comparable they are to furries’ actual and subjective age.

Disabilities in the Fandom

1. How prevalent are different disabilities in the furry fandom?

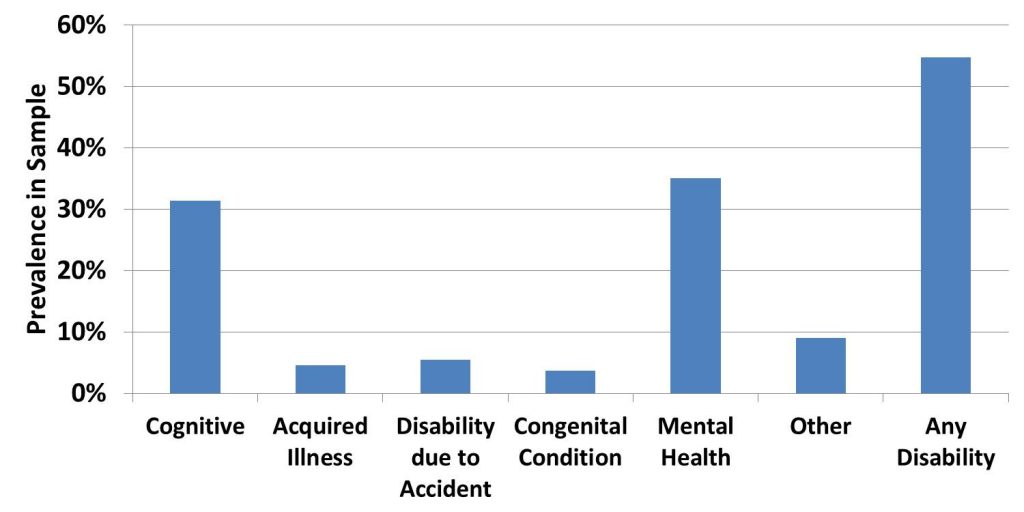

Answer: The most common disabilities self-identified in the furry fandom are learning, communication, cognitive, and other mental disabilities. Other, more physical disabilities (e.g., acquired illness, brain injuries, and congenital conditions) were far less common, though they were very much present (see figure below). Just over half of furries indicated that they had one or more disability.

2. Does having a disability affect one’s well-being? Does it affect one’s fursona?

Short answer: Furries who self-identify as having a disability are more likely than furries without a disability to experience depression and anxiety and have a lower self-esteem. In addition, furries with a disability are more likely to say that one of the functions of their fursona is to allow them to interact with others without being judged. Furries with a disability are also more likely to say that their fursona represents who they wish they were.

Long answer: We compared furries who self-identified as having a disability with those who did not on a number of variables using a series of t-tests. To start, we discovered that furries with disabilities reported experiencing greater depression (M=2.99/7.00) than those without disabilities (M=2.14/7.00; t(233)=3.87, p<.001), greater anxiety (M=3.82/7.00 vs. M=2.71/7.00; t(237)=4.79, p<.001), and less self-esteem (M=4.77/7.00 vs. M=5.53/7.00; t(236)=4.71, p<.001). These findings are not particularly surprising, given that, included among those self-identifying with disabilities are mental disorders, which may include anxiety disorders and mood disorders. We were interested, however, in whether having a disability might also impact the function of one’s fursona, given prior IARP research showing that many furries strive to become more like fursonas that represent idealized versions of themselves. Present data supports this idea, as furries with disabilities were more likely to state that their fursona allowed them to take a break from being judged (M=4.79/7.00 vs. M=4.06/7.00; t(234)=2.59, p=.010) and that their fursona represented who they wished they were (M=5.14/7.00 vs. M=4.44/7.00; t(235)=2.54, p=.012). These data suggest that furries with disabilities may use their fursonas, most of whom do not have the same disability that they have (my fursona has the same disability that I have, average = M=3.00/7.00), as a way of temporarily escaping the stigma and negative attention they receive in their daily life as a result of their disability.

3. How do furries with disabilities use their fursonas?

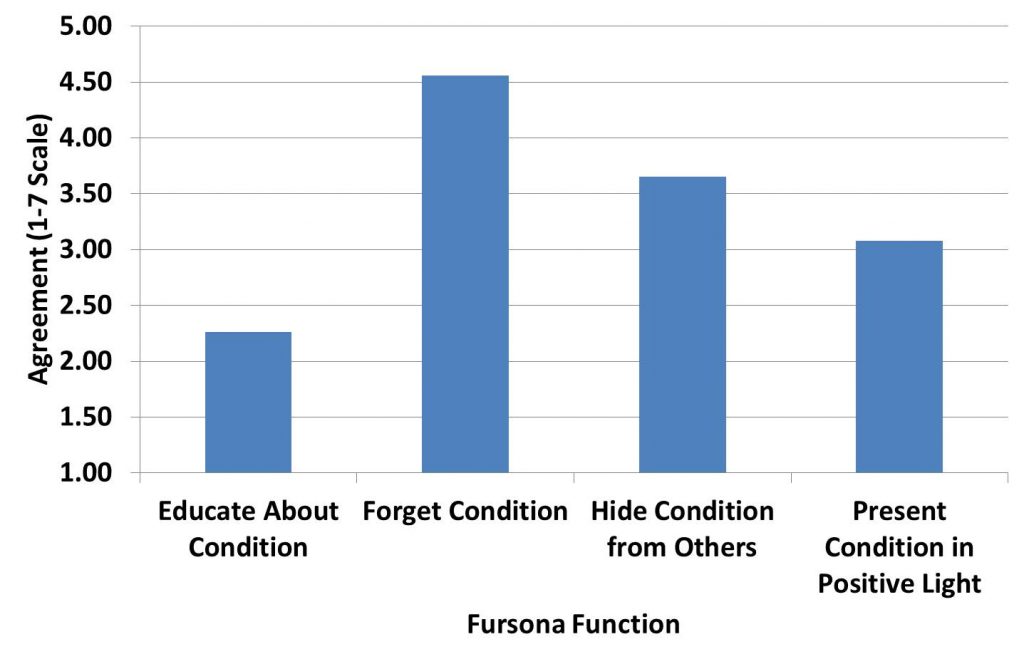

Short answer: While some furries with disabilities may use their fursonas to educate others about their disability or to redefine their disability in a positive light, one of the most commonly stated functions of fursonas includes the ability to forget about one’s disability or to hide one’s disability while interacting with others. These findings are in line with what many persons with disabilities state – that, ultimately, they do not wish to be treated differently because of their condition. It would seem that, for many, having a fursona without their disability allows them to do just that.

Long answer: As the above figure indicates, furries with disabilities used their fursonas for different functions, with some functions being more frequently adopted than others (F(3,284)=32.21, p<.001). In particular, the most popular fursona function for furries with disabilities was as a means of forgetting one’s condition (p<.001 for all “forget” vs. condition differences), while hiding one’s condition when interacting with others was the second most popular function. Follow-up regression analyses revealed that furries were more likely to use their fursona to hide their disability when interacting with others when they had low self-esteem (B = -.340, p=.037) or if they experienced significant depression (B = .298, p=.063) or anxiety (B = .347, p=.037). This suggests that the use of one’s fursona to interact with others might seem more feasible when one is experiencing significant distress or dissatisfaction with themselves. In contrast, the use of one’s fursona to temporarily forget about their condition was unrelated to psychological well-being (all ps >.70).

Long answer: As the above figure indicates, furries with disabilities used their fursonas for different functions, with some functions being more frequently adopted than others (F(3,284)=32.21, p<.001). In particular, the most popular fursona function for furries with disabilities was as a means of forgetting one’s condition (p<.001 for all “forget” vs. condition differences), while hiding one’s condition when interacting with others was the second most popular function. Follow-up regression analyses revealed that furries were more likely to use their fursona to hide their disability when interacting with others when they had low self-esteem (B = -.340, p=.037) or if they experienced significant depression (B = .298, p=.063) or anxiety (B = .347, p=.037). This suggests that the use of one’s fursona to interact with others might seem more feasible when one is experiencing significant distress or dissatisfaction with themselves. In contrast, the use of one’s fursona to temporarily forget about their condition was unrelated to psychological well-being (all ps >.70).

Going forward, we hope to follow up on this research with further work on those with disabilities in the fandom, delving more into the mechanisms underlying, and overall effectiveness of, using one’s fursona as a potential resource for coping with the stigma or stress of having a disability.

Women in the Fandom

Preface: The research in this section represents a follow-up to research conducted by the IARP over the last year regarding the issues women experience as members of a predominantly-male fandom. Based on feedback obtained through a number of focus groups and targeted surveys, which suggested that many women feel that they struggle with feelings that they do not belong in the fandom or that they are constantly reminded of their gender as they interact in the fandom, we sought to extend these findings to the fandom more broadly and to compare the experience of women in the fandom to the experience of men in the fandom.

It should be noted that while the data presented below compare men and women in the fandom, this is being done solely for the purpose of simplicity of presentation and data analysis. The IARP fully recognizes the diverse range and fluidity of gender identity, and in no way wishes to imply that gender identity is dichotomous or in any say a simple matter of being a “man or a woman”.

1. Are women “less furry” than furry men?

Short answer: No. Women do not differ significantly from men in the number of years they have been members of the furry fandom, in their felt closeness to their fursonas, or in the extent to which they self-identify as furries. Despite having been in the fandom for a comparable time as men, and identifying as furry at rates comparable to men, however, women report feeling less like a member of the furry community than men, and report wanting to retain aspects of non-furry culture more than men, who are more likely to want to exclusively be a part of furry culture and to eschew non-furry culture.

Long answer: When asked how many years they had considered themselves a furry for, women (M=9.27 years) did not differ statistically significantly from men (M=11.02 years; t(211)=0.99, p=.326). Moreover, when asked, on a 7-point scale, how much overlap they saw between themselves and their fursona, women (5.05) did not differ statistically significantly from men (M=5.13; t(54)=0.23, p=.821). Finally, when asked whether they strongly identified with being a furry on a 7-point scale, women (M=4.88) did not differ statistically significantly from men (M=5.35; t(233)=1.55, p=.122). Taken together, these data suggest that, for all intents and purposes, women seem to be about “as furry” as men in the fandom. In the language of fan psychologists, they are comparable to men with regard to “fanship” – being an enthusiastic supporter of the content of a fandom.

The evidence also shows that, despite being comparably furry, women are less likely than men to feel a sense of “fandom” – feeling a sense of kinship with others sharing the same fan interests. For example, when asked whether they identified as a member of the furry community, women (M=5.22) agreed less with the statement than men did (M=6.01; t(64) = 2.54, p=.013). One follow-up question asked participants to what extent they wanted friends who were both furries and non-furries: women were more likely to desire furry and non-furry friends (M=6.56) than men (M=6.14; t(80)=2.28, p=.025). Women were also more likely to want to retain non-furry culture in addition to furry culture (M=5.93) than men (M=5.27; t(208)=2.34, p=.020). As a whole, these data seem to suggest that males feel a strong sense of belonging in the furry fandom, to the point where they feel little need to look outside the fandom for friends or other needs. In contrast, females experience less of this, perhaps in part because the fandom may seem less welcoming to them, or less like a place that fulfills their social needs entirely.

2. Is the experience of the furry fandom different for women than it is for men?

Short answer: Somewhat. On the one hand, men and women are comparable in the extent that they feel they can “be themselves” in the furry fandom, in the extent to which they receive unwanted attention, and in their feelings of non-belonging within the fandom. On the other hand, women are more likely to have their gender brought up when interacting within the fandom, and are far less comfortable with the portrayal of women in furry artwork, and with pornography in the fandom more generally. These factors, and factors related to them, while perhaps not necessarily leading to women feeling unwelcome in the fandom, may nevertheless lead to women feeling less identification with the furry fandom than men. This will be the subject of future research.

Long answer: When asked whether they felt like they could be themselves in the furry fandom, women (M=6.22) did not differ significantly from men (M=5.98; t(207)=1.01, p=.316). Women also did not differ significantly from men in the extent to which they received unwanted attention from others in the fandom (M=3.20 vs.M=2.88; t(207)=1.03, p=.304), nor in the extent to which they felt like they didn’t belong in the fandom (M=2.83 vs. M=2.55; t(207)=0.90, p=.371). These figures suggest that men and women do not differ with regard to the extent that they explicitly felt or experienced signals that they were not welcome or did not belong in the fandom.

That said, women did report other experiences, more subtle ones, that may lead them to associate less with the furry fandom. For example, women (M=4.39) were less likely than men (M=5.07) to say that their gender never came up while interacting in the fandom (t(206)=2.08, p=.039), suggesting that others in the fandom more frequently make women aware of the fact that they are a woman in a predominantly fandom comprised predominantly of men. This may serve as a cue to women about the appropriateness of their being in the fandom, as exemplified by the fact that women (M=3.80) were less likely than men (M=4.44) to feel like an “ideal” furry (t(230)=2.40, p=.017). Another potential cue that may make women feel less comfortable in the furry fandom has to do with the portrayal of women in the fandom; while women (M=4.56) and men (M=5.20) were comparable in their comfort with the way men were portrayed in furry art (t(207)=1.53, p=.129), women (M=4.56) were far less comfortable than men were (M=5.20) with the way women were portrayed in furry artwork (t(207)=2.28, p=.024). This discomfort with portrayal of women in artwork has been raised in focus groups, where women emphasized feeling discomfort with unrealistic portrayals of the female body and with themes of sexual coercion and the reduction of women to sex objects in art. This may explain a final point in the data, where women (M=2.56) reported feeling greater discomfort when viewing furry pornography than men (M=1.85; t(52)=2.11; p=.040). While the present data don’t address the specific reasons for this discomfort, future research may shed light on this discomfort, the reasons for it, and the possible effects it may have, as informed by focus groups and the present findings.

Artists in the Fandom

Preface: The research in this section represents a follow-up to research conducted by the IARP over the last year regarding the issues artists encounter in the fandom. These issues range from an artist’s felt identity within the fandom (are they an “artist first and a furry second, or vice-versa?”), their interaction with customers in the fandom, and the issues they encounter as a result of being members of a highly-regarded subgroup within the fandom. While the data here represent only a small, targeted sample of artists, we hope, in the next year, to supplement these findings with a much larger, representative sample of artists.

1. Are furries entitled, or are artists overly sensitive?

Short answer: The data suggest that, as a group, furries are less entitled than artists estimate they are. This does not, however, mean that artists are being “overly sensitive” or that they do not experience a significant amount of entitlement from particular fans. There is a well-studied psychological phenomenon known as the “availability heuristic”, which, put simply, means that people estimate the frequency with which something occurs based on how readily examples comes to mind. Research on memory suggests that the memories which most readily come to mind are those which are the most intense and most distinct. In other words, we hypothesize that artists may be overestimating the fandom’s overall sense of entitlement due to this availability heuristic: a “few bad apples” are disproportionately influencing the perception of the entire fandom as a group. This isn’t to say that artists don’t recognize that most furries aren’t extremely entitled. But it does suggest that one “bad experience” with a customer may have subtle, lasting effects on artists in the fandom.

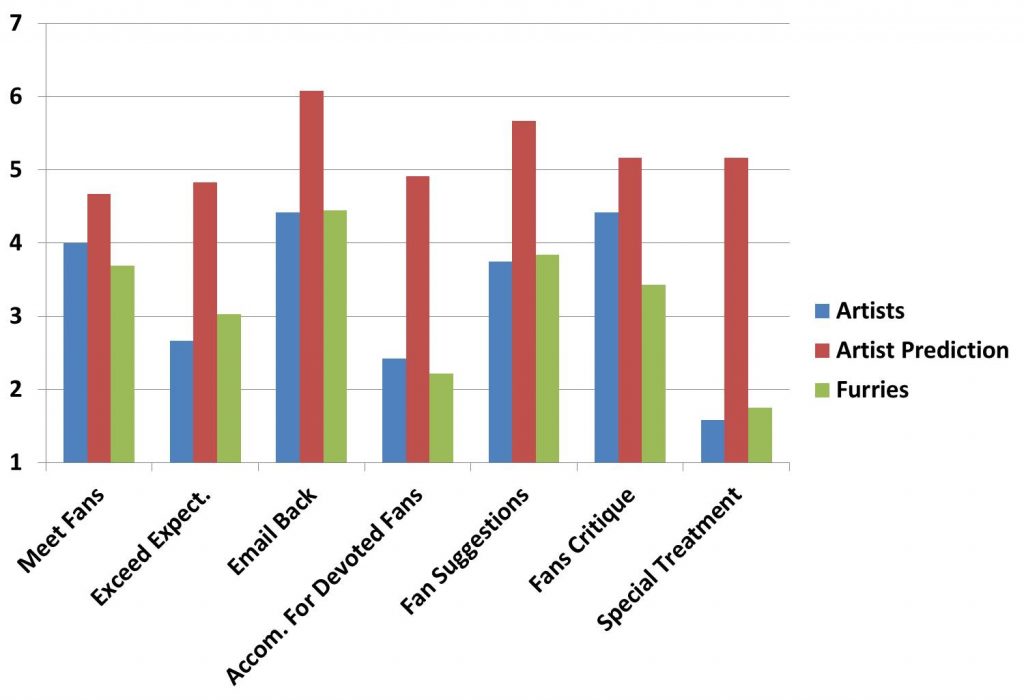

Long answer: To address this question, we asked artists about a series of seven questions covering different fan behaviours, beliefs, and attitudes, each one different with regard to how “entitled” it was. These items asked about the extent to which artists were expected to meet fans in person, the obligation for artists to exceed customer expectations, the obligation of the artist to respond to fan e-mails, the extent to which artists made accommodations for devoted fans, the artist’s obligation to take fan suggestions, the artist’s obligation to listen to, and take, fan criticism, and the obligation for artists to give special treatment to particular fans. Artists were first asked to indicate, for each item, the extent to which they personally endorsed each item on a 1-7 scale. Then, they were asked to indicate the extent to which they believed the average furry endorsed each item.

It is apparent, by comparing the blue and red bars, that for each item, artists felt that fans held far more entitled beliefs than they did. But were artist predictions of fans accurate? The green bars represent actual responses given by 1,010 furries attending Anthrocon 2014 on the exact same items. On nearly every item, it seems that furries’ beliefs about the appropriateness of each of these behaviours was comparable to that of artists, and nowhere near the level predicted by artists.

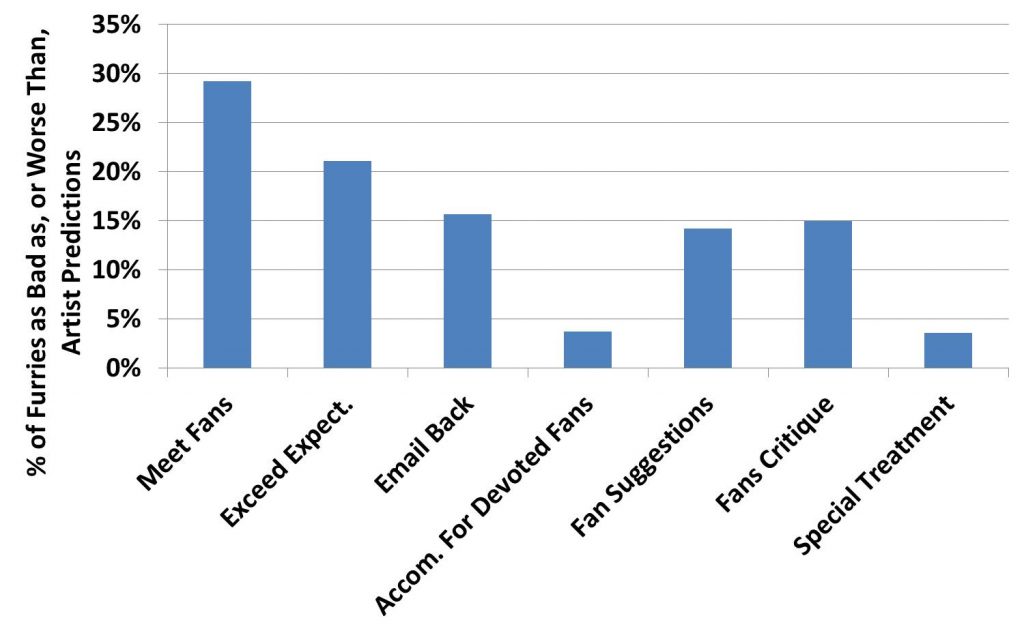

This raises the question of what would lead artists to overestimate the prevalence of this entitled behaviour? In the “short answer” above, we outline one possibility, based on the availability heuristic, which would suggest that even a small group of particularly entitled fans may cause artists to drastically overestimate the prevalence of entitled behaviour in the fandom. Just how frequent is the negative behaviour that artists predict?

The figure illustrates that the two behaviours artists find the most entitled and deplorable (asking for special treatment and making accommodations for devoted fans) are also the ones that they overestimate the prevalence of the most, suggesting that rare encounters with these very few individuals may be driving artists’ perception of entitlement in the fandom.

The figure illustrates that the two behaviours artists find the most entitled and deplorable (asking for special treatment and making accommodations for devoted fans) are also the ones that they overestimate the prevalence of the most, suggesting that rare encounters with these very few individuals may be driving artists’ perception of entitlement in the fandom.

2. Some statistics about furry artists.

Answer: We asked our sample of furry artists to answer questions about their policies and their experience doing artwork in the furry fandom. One set of questions dealt with the issue of mature and restricted content created by artists. On average, the artists in our sample said that 15.25% of the work they produced was “adult” in nature. 75% stated that they had been asked at least once to create something that they were not personally comfortable with. As a follow-up, 67% of artists stated that they had a posted list of content that they would not produce (e.g., particular fetishes or themes, etc…), and 58% said they had a posted terms of service outlining the rules for commissioning them.

Unrelated, we also asked artists about the feedback they received from fans. They acknowledged that the feedback they got from fans was overwhelmingly positive, estimating, on average, that about 5.5% of the feedback they received was negative. Finally, artists indicated that most of their friends in the fandom (61.3%) were also artists, suggesting that there may be some merit to considering “artists” to be a distinct and cohesive subgroup within the fandom.

3. What are the biggest issues between commissioners and artists?

Short Answer: When asked, both artists and commissioners seemed to agree that many of the biggest problems arising during commissions pertained to issues of communication between the client and the artist, whether the client is being unclear about their expectations or failing to read the artist’s terms of service, or the artist being unclear about their timeline or their workload. Artists would do well to establish a clear and visible terms of service and ensure that their clients are informed about their workload and reasonable expectations for delivery and correspondence. Commissioners would do well to read an artist’s terms of service carefully, to ensure that they provide artists with clear and precise expectations (e.g., reference sheets, descriptions), and to ensure that they have realistic expectations about what the artist can produce.

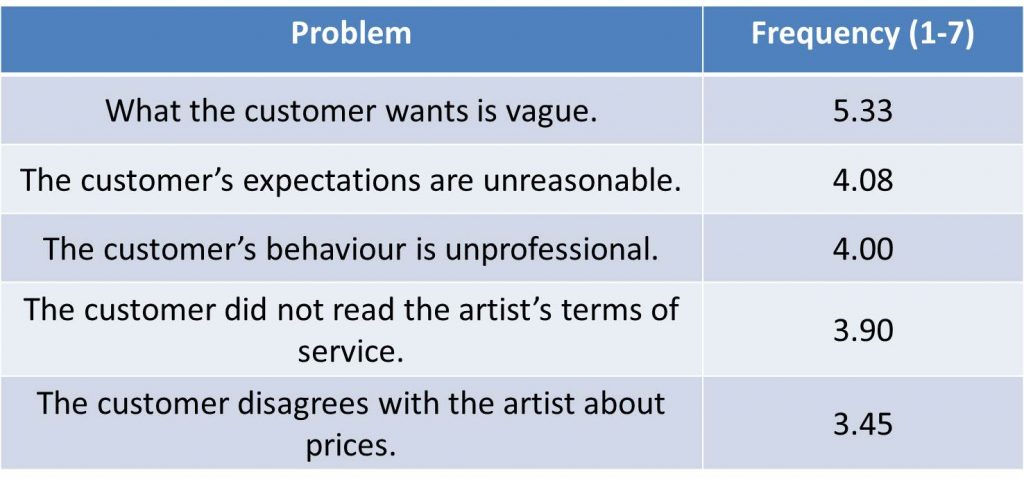

Long Answer: We asked artists to rate the extent to which different problems (generated from artist focus groups) could explain the majority of issues that arose between the artist and their clients. The five most commonly referenced problems (along with ratings of how commonly each problem occurred, on a 1-7 scale) were:

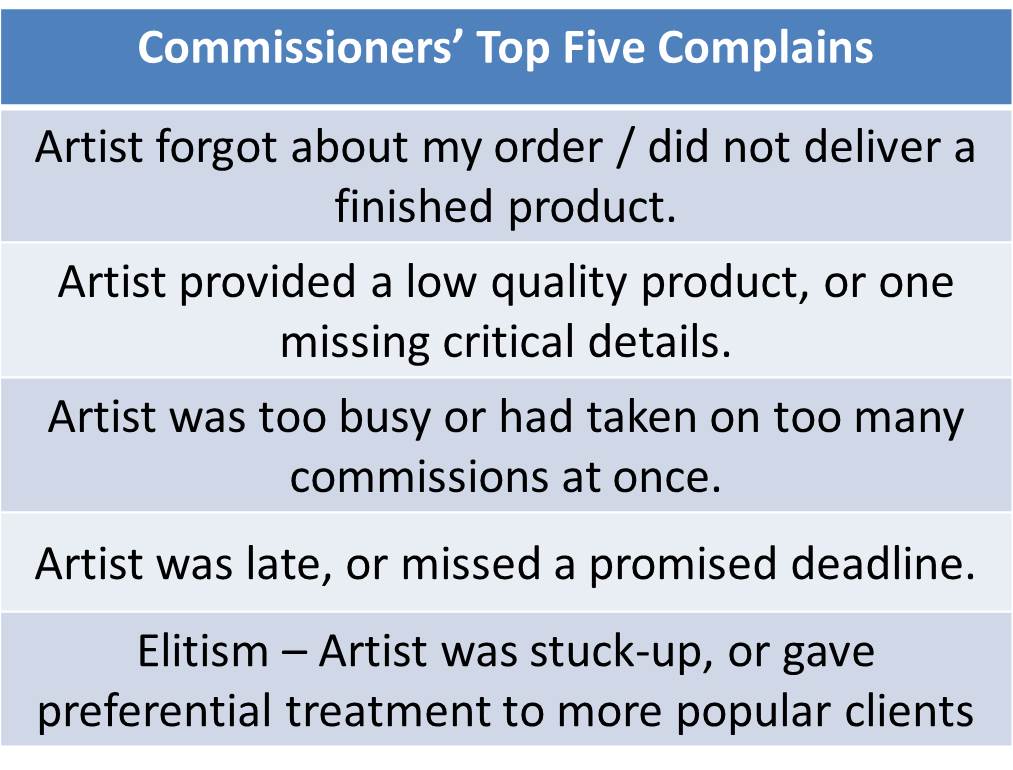

We also asked customers to rate the frequency with which different problems led to issues with artists with whom they had commissions. The most commonly cited problems chosen from the list provided included difficulties communicating with the artist (e.g., unresponsive to e-mail), the commissioner being unclear about what, precisely, they wanted, and the artist setting unreasonable prices. We also asked participants to provide their own list of problems that arose. From this open-ended format, several problems commonly emerged among commissioners:

We also asked customers to rate the frequency with which different problems led to issues with artists with whom they had commissions. The most commonly cited problems chosen from the list provided included difficulties communicating with the artist (e.g., unresponsive to e-mail), the commissioner being unclear about what, precisely, they wanted, and the artist setting unreasonable prices. We also asked participants to provide their own list of problems that arose. From this open-ended format, several problems commonly emerged among commissioners: As was suggested in the “short answer” section above, it seems like many of the common complains of both artists and commissioners can be avoided through clear communication, both of the commissioner’s expectations, but also of the artist’s terms of service and their ability to accommodate the commissioner’s request in the expected time frame.

As was suggested in the “short answer” section above, it seems like many of the common complains of both artists and commissioners can be avoided through clear communication, both of the commissioner’s expectations, but also of the artist’s terms of service and their ability to accommodate the commissioner’s request in the expected time frame.

Pornography in the Fandom

Preface: The research in this section represents one of the IARP’s first attempts to study and compare pornography and perceptions of it in the furry fandom to pornography and perceptions of it outside of the fandom. This research was conducted with the intent of testing a hypothesis regarding furries’ perception of pornography when it came to furry artwork. In particular, we hypothesized that, due to the stigmatized nature of the furry fandom, furries may be particularly vigilant when it comes to the perception of fandom content by outsiders. As such, we thought that, insofar as furries perceived significant cultural stigma, they would be more likely than non-furries to call furry artwork “pornographic”.

The methodology employed in this research is described more fully in the “Methods” section at the start of this write-up. It is worth briefly elaborating on the images used in this study. All images, fursuit, clean, nude, erotic, and explicit, both furry and non-furry, were collected by collecting a random sample of images from various websites and from Google searches. The images were collected at random to avoid selection bias (e.g., selecting pictures based on popularity, style, quality, etc…), and were chosen to fit particular quotas: for each category, pictures portraying both heterosexual and homosexual (both male and female) were chosen. Watermarks, artist signatures, website urls, and other clues to the art’s origin were cropped from the pictures to avoid having those cues influence participants’ rating of each image. For present purposes, “clean” images refer to images portraying a single character whose genitals are covered by clothing. “Nude” images consist of images portraying a single character without any clothing and whose genitals are clearly visible. “Erotic” images consist of two characters (same sex or opposite sex) who are both naked and for whom there is contact with at least one character’s genitals, but without penetrative intercourse (oral, vaginal, or anal). “Explicit” images consists of two characters (same sex or opposite sex) who are both naked and in which there is penetrative intercourse or genital-genital contact. Finally, “fursuit” images consisted of a single, full-fursuit person in a non-erotic position looking toward the camera.

It is worth noting that, in the course of random assignment, pictures emphasizing fetishes (e.g., BDSM) were removed from the sample. This removal was to ensure that sample pictures were as comparable as possible to one another, and to ensure that the perceived pornographic content of each image was based solely on the characters and the actions being done in the images, and not due to preexisting associations of particular accessories or themes with pornography.

Finally, the IARP emphasizes that these data are being presented in a value-neutral, non-judgmental manner. In no way do we wish to make moral statements about pornography or prescriptive statements about the role or appropriateness of pornography in the furry fandom.

1. Are furries more likely than non-furries to call furry artwork “pornographic”?

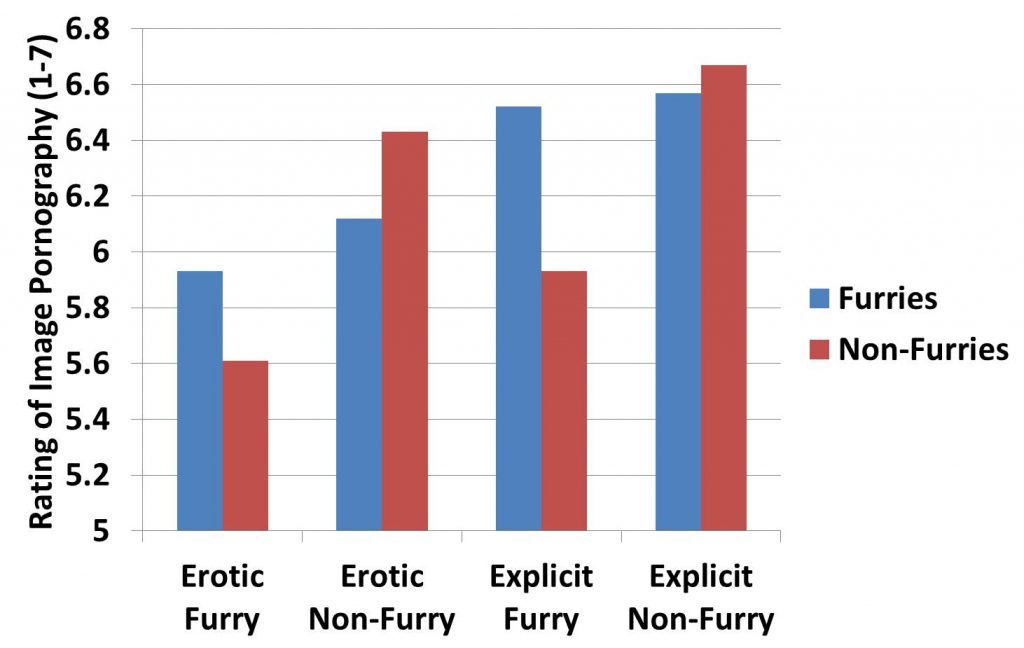

Short answer: Yes. The data show that while furries and non-furries did not consistently differ in the extent to which they considered “clean” or “nude” images pornographic (furry or otherwise), they did differ when it came to images of fursuits, erotic images, and explicit images. Furries rated fursuits, furry-themed erotic images, and furry-themed explicit images as being more pornographic than non-furry participants, even after controlling statistically for gender differences between the two samples. In contrast, non-furry participants rated the non-furry erotica as being more pornographic than the furry erotica, and furries and non-furries did not significantly differ when it came to rating how pornographic non-furry explicit images were. In sum, there is evidence that furries do consider furry artwork more pornographic than non-furries do, driven, at least in part, by differences in how arousing participants found the pictures to be (the more arousing a picture was, the more likely it was to be considered pornographic).

Long answer: Furries (M=5.93) were marginally more likely than non-furries (M=5.61) to call furry erotic images pornographic (t(190)=1.90, p=.060), but showed the opposite pattern when it came to non-furry erotic images (M=6.12 vs. M=6.43, t(129)=2.39, p=.018). This same data was also run as a repeated measures ANOVA, where a significant interaction was found between participant sample (furry vs. non-furry) and artwork type (furry or non-furry; F(1,189)=15.75, p<.001). Difference scores (furry erotica – non-furry erotica) were also calculated for furries and non-furries, and were tested with an ANOVA, showing that non-furries (difference = -.827) were making a distinction between furry and non-furry pornography that furries (difference = -.186) were not (F(1,189)=12.17, p<.001).

Long answer: Furries (M=5.93) were marginally more likely than non-furries (M=5.61) to call furry erotic images pornographic (t(190)=1.90, p=.060), but showed the opposite pattern when it came to non-furry erotic images (M=6.12 vs. M=6.43, t(129)=2.39, p=.018). This same data was also run as a repeated measures ANOVA, where a significant interaction was found between participant sample (furry vs. non-furry) and artwork type (furry or non-furry; F(1,189)=15.75, p<.001). Difference scores (furry erotica – non-furry erotica) were also calculated for furries and non-furries, and were tested with an ANOVA, showing that non-furries (difference = -.827) were making a distinction between furry and non-furry pornography that furries (difference = -.186) were not (F(1,189)=12.17, p<.001).

When it came to explicit images, furries (M=6.52) were significantly more likely to call furry images pornographic than non-furries (M=5.93; t(187)=4.03, p<.001), but did not differ from non-furries when it came to rating explicit non-furry pictures (M=6.57 vs. M=6.67, t(191)=1.09, p=.277). As above, this same data was also run as a repeated measures ANOVA, where a significant interaction was found between participant sample (furry vs. non-furry) and artwork type (furry or non-furry; F(1,189)=17.33, p<.001). Difference scores (furry explicit – non-furry explicit) were also calculated for furries and non-furries, and were tested with an ANOVA, showing that non-furries (difference = -.741) were making a distinction between furry and non-furry pornography that furries (difference = -.053) were not (F(1,189)=15.75, p<.001).

In short, the primary difference between furries and non-furries seems to be the fact that non-furries are not calling erotic and explicit furry material pornography, whereas furries are. Follow-up mediation analyses suggest that this effect is driven predominantly by arousal, at least for the explicit images (Indirect effect = .200, 95% CI = .032 to .407; p = .033); the mediation, while in the same direction, did not reach significance for erotic images (p=.145). Put simply: if participants found the material arousing, they considered it pornographic. Since non-furries did not find the non-furry artwork as arousing as furries did, they did not consider it as pornographic as furries did.

Finally, when it came to fursuit pictures, furries (M=1.23) rated the same images as more pornographic than non-furries did (M=1.09; t(98)=3.02, p=.009). This may suggest that furries may be more likely than non-furries to consider fursuits in a sexual, pornographic way, and has interesting implications for the sorts of concerns furries have regarding public perception of the fandom – something which will be the subject of future research.

2. How do furries and non-furries think the other feels about porn?

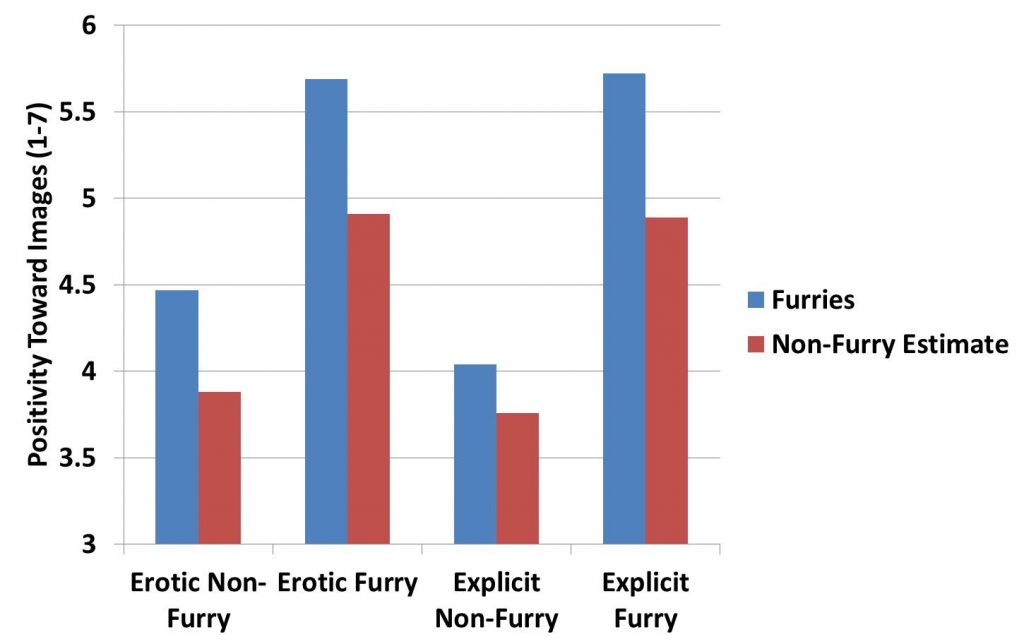

Short answer: In general, furries greatly overestimate how negatively non-furries will respond toward furry erotica and explicit furry material, and overestimated how positively non-furries felt toward non-furry material (though they correctly estimated that non-furs prefer non-furry material). In contrast, non-furries greatly underestimated how positively furries felt about both furry and non-furry material, though they correctly estimated that furries were more interested in furry images than non-furry images.

Long answer: The top figure above illustrates how furries felt toward furry and non-furry erotica and explicit images (blue bars), and how non-furries estimated that furries would feel toward these things. It’s apparent given the fact that the red bars are all lower than the blue bars, that non-furries underestimated how positively furries would feel toward erotic and explicit material (which contrasts with how many furries expect non-furries to feel toward them, based on mischaracterizations of the furry fandom as being little more than a fetish). It would seem, however, that non-furries correctly inferred that furries would be preferentially positive toward furry artwork as compared to non-furry artwork (as indicated by the “furry” bars being higher than the “non-furry” bars.

Long answer: The top figure above illustrates how furries felt toward furry and non-furry erotica and explicit images (blue bars), and how non-furries estimated that furries would feel toward these things. It’s apparent given the fact that the red bars are all lower than the blue bars, that non-furries underestimated how positively furries would feel toward erotic and explicit material (which contrasts with how many furries expect non-furries to feel toward them, based on mischaracterizations of the furry fandom as being little more than a fetish). It would seem, however, that non-furries correctly inferred that furries would be preferentially positive toward furry artwork as compared to non-furry artwork (as indicated by the “furry” bars being higher than the “non-furry” bars.

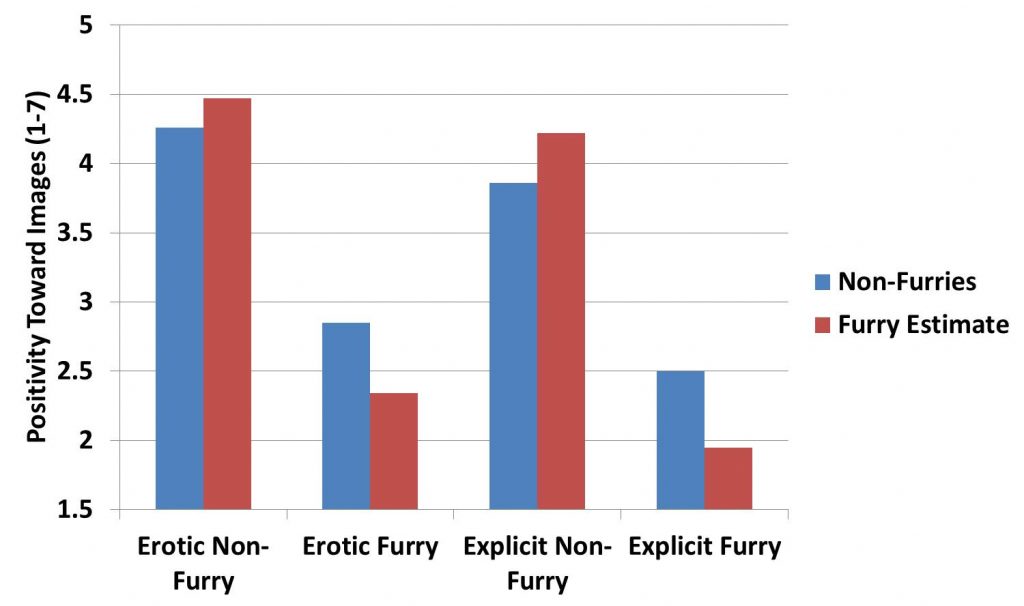

A near-perfect reversal of the phenomenon happens on the below figure, which shows how non-furries responded to the images, and how furries predicted that the non-furries would respond. Of greatest importance in this figures are “Erotic Furry” and “Explicit Furry” categories, where we see evidence of furries’ expectation of non-furry disapproval: furries significantly underestimated how negatively non-furries would feel toward furry images. Moreover, furries overestimated the extent to which non-furries would feel positively toward non-furry material (though, like non-furries, furries did get the pattern correct, where non-furries preferred non-furry art to furry art).

The significance of the data for the furry fandom seems to be that furries overestimate how negatively non-furries perceive the furry fandom and its content. While non-furries certainly show greater preference for non-furry pornography as compared to furry pornography, the anticipated revulsion toward furry artwork that many furries anticipate from non-furries seems to be overblown, at least in this particular sample of non-furries. In the future, we hope to test the generalizability of these findings to other samples of furries, other samples of non-furries, and using other samples of artwork.

Furries and Face Recognition

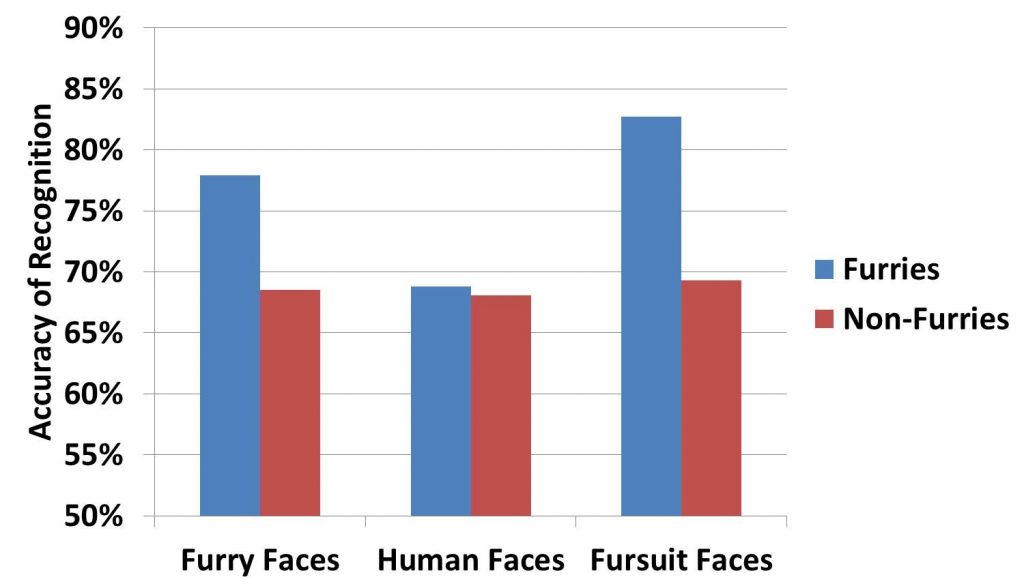

1. Do furries and non-furries differ in their ability to recognize human faces? Furry faces? Fursuits?

Short answer: Yes. After having furries and non-furries look at 100 images of fursuits, furry artwork, and non-furry artwork, it seems that while furries and non-furries do not differ in their ability to recognize human faces, furries are more accurate when it comes to recognizing faces in furry artwork and fursuit faces. The effect is likely driven by exposure to, and familiarity with, the content of the furry fandom, which makes it easier for furries to make distinctions (e.g., “a feral wolf suit”, “an anthro fox suit”, “a blue cat suit”) that non-furries do not make (e.g., “a fuzzy suit”, “another fuzzy suit”, “another fuzzy suit”).

Long answer: After collapsing across two types of trials (whether or not you correctly say “no” when presented with a novel face, and whether or not you correctly say “yes” when presented with a face previously presented), we conducted a series of t-tests to determine whether furries’ performance was better than non-furries when it came to recognizing fursuits, faces from furry artwork, and human faces. The results revealed that furries and non-furries did not significantly differ with regard to recognizing human faces (t(182)=.445, p=.657). In contrast, furries outperformed non-furries when it came to recognition of furry faces (t(182) = 5.25, p<.001) and the recognition of fursuit faces (t(182)=6.86, p<.001). Interestingly, it appears that non-furries did about as well on furry / fursuit faces as they did on human faces. This suggests that the difference between furries and non-furries wasn’t driven by the fact that non-furries were bad at recognizing furry faces and fursuit faces (they still did well above chance). It suggests, rather, that furries are particularly good (and possibly motivated) to recognize furry faces and fursuits.

Long answer: After collapsing across two types of trials (whether or not you correctly say “no” when presented with a novel face, and whether or not you correctly say “yes” when presented with a face previously presented), we conducted a series of t-tests to determine whether furries’ performance was better than non-furries when it came to recognizing fursuits, faces from furry artwork, and human faces. The results revealed that furries and non-furries did not significantly differ with regard to recognizing human faces (t(182)=.445, p=.657). In contrast, furries outperformed non-furries when it came to recognition of furry faces (t(182) = 5.25, p<.001) and the recognition of fursuit faces (t(182)=6.86, p<.001). Interestingly, it appears that non-furries did about as well on furry / fursuit faces as they did on human faces. This suggests that the difference between furries and non-furries wasn’t driven by the fact that non-furries were bad at recognizing furry faces and fursuit faces (they still did well above chance). It suggests, rather, that furries are particularly good (and possibly motivated) to recognize furry faces and fursuits.

We attempted to test one possible explanation for this difference: mere exposure. Perhaps it’s the case that furries simply see more furry content and fursuits, which might explain why they outperformed non-furries (e.g., more fully developed concepts in their minds, allowing them to make more subtle distinctions). Mediation analysis suggests there may be some truth to this: the frequency with which participants encountered fursuits (and presumably other furry fandom content – this wasn’t explicitly asked in this study) significantly mediated the difference between furries and non-furries on furry face recognition (Indirect effect = .041, SE = .012, p <.001) and on fursuit recognition (Indirect effect = .023, SE = .011, p = .038).

Future research will attempt to not only replicate these findings, but test some of the other possible mechanisms underlying these findings, and the implications of these findings in other domains (e.g., regarding attitudes toward animals, recognition of animals, and humanization of non-human animals).

Recent Comments