This was our first attempt at an online furry survey. Initially, it was intended to gather a sample of 250-500 furries from a handful of groups across North America. What we did NOT count on, however, was the word-of-mouth spreading of our survey’s link and the enthusiasm of furries for scientific research on their community! In total, we received nearly 7,000 participants from 70 different countries across 6 continents! After removing minors from the sample (our ethics board unfortunately prohibits us from conducting research on minors) and removing “junk data” (e.g. participants who answered only one question or who wrote bogus, malicious or obviously ridiculous responses), our sample consisted of 4,338 furries and 485 non-furries. The non-furries were particularly interesting, because they allow us to have a “control group” for our study—a baseline to compare furries to.

In sum, the survey consisted of more than 170 questions. You can understand, given the sheer volume of data, that it has taken considerable time to analyze this data, and while we are still working on it, we do have some preliminary statistics and demographic information we can display. They are based on a talk Nuka gave at Furnal Equinox 21 and are presented her in a Q&A format. If you have any questions or want clarification, please contact us (see link on the sidebar).

Please note that all collected information is presented here in aggregate (summarized) form, and there is absolutely NO identifying information in the data. We have no way of tracing responses back to the original participant (this is an anonymous survey). Additionally, any unique responses (e.g. species types selected by only one person) are not reported, to protect the anonymity of the participants.

Summary of questions:

Demographics

Q1: How old is the average furry?

Q2: Where are the furries in your sample from?

Q3: How did furries find out about your survey?

Q4: Is it true that the furry community is almost all male?

Q5: Are furries “nerds”? How do they stack up against non-furries in terms of education?

Q6: Are furries spiritual?

Furry Statistics

Q7: How do you know the furries in your sample are different from non-furries? Are they “more furry”?

Q8: How long has the average furry been a furry?

Q9a: Do furries think they’re human? Are they people who want to be animals?

Q9b: Does furry type matter?

Q10: Is furry a “choice”? does a person have any control over whether or not they are a furry?

Gender and Sexual Orientation

Q11: What about the gender of furries?

Q12: Do furries pick fursonas that are the same gender as their own?

Q13: Are furries “more gay” than non-furries?

Self-Disclosure

Q14: Are most furries “in the closet” about their furriness?

Species Questions

Q15: Why do furries choose the species they do?

Q16: How many fursonas has the average furry had?

Q17: What are the most popular species?

Q18: Did location affect species choice?

Q19: Does species choice matter?

Reasons for Being in the Furry Community

Q20: Why are furries really furries? Is it for attention? Sex? Self-expression? Something else?

Furry Well-Being

Q21: Are furries “messed up”? People with low self-esteem/ other problems?

Furry Demographics

Q1: How old is the average furry?

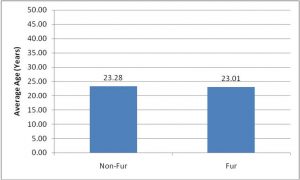

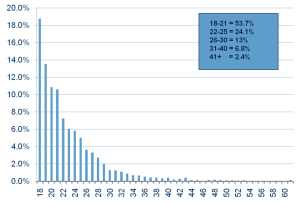

This question has two answers: on the one hand, the average age of all of the furries collected in our sample was approximately 19 years old. However, as we were not allowed to use data from minors in our survey, for the rest of our analysis we removed data provided by minors. As such, we ended up with a sample of furries whose average age was 23.0 years old. This is comparable to our non-furry control group, whose average age was 23.3 years old.

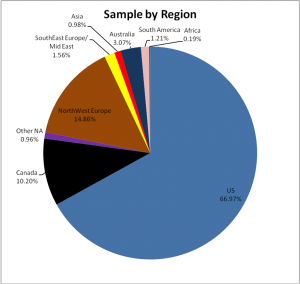

Q2: Where are the furries in your sample from?

We asked participants to indicate what country they came from. Given the sheer number of countries indicated (nearly 70), and the difficulty of portraying all those different countries in a single pie-graph, we grouped responses into meaningful groups, displayed below.

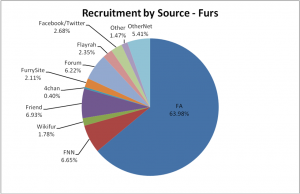

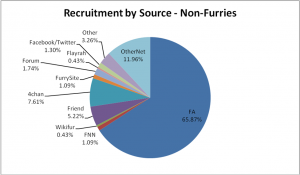

Q3: How did furries find out about your survey?

While we initially targeted a number of local furry forums for our survey, we also contacted Fur Affinity, Wikifur, the Furry News Network, Pounced and Flayrah, who were kind enough to post notices of our survey. From there, news of our survey spread. As you can see below, while many of our participants came from FurAffinity, a significant proportion of our sample found out about our survey in a variety of ways. Interestingly enough, many of our non-furry participants also found out about our survey from FurAffinity and other furry websites.

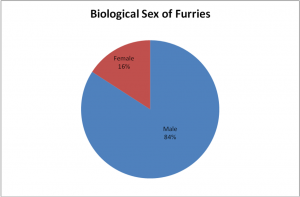

Q4: Is it true that the furry community is almost all male?

It appears from our data that the furry community is indeed a primarily male one. That said, there is both anecdotal evidence and perhaps a hint of evidence from past surveys to suggest that the proportion of females in the community is growing. Also note that the percentages in this figure are rounded up and that there is a very small proportion of the fandom that is intersex, hermaphroditic or “other” (not displayed here).

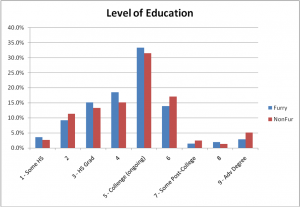

Q5: Are furries “nerds”? How do they stack up against non-furries in terms of education?

As you can see from the figure below, there are no significant differences between furries and non-furries in terms of formal education (the figure goes from 1-9, with 1 representing only some high school education and 9 representing an advanced degree; 2 = ongoing high school, 4 = some college, 6 = college degree, 8 = ongoing advanced degree). You’ll notice that furries are decently educated, with about 85% of the community having a high school education or higher and nearly 33% reported currently being in college or some form of post-secondary education. Interestingly enough, 2-3% of furries have an advanced degree (Masters or Doctorate).

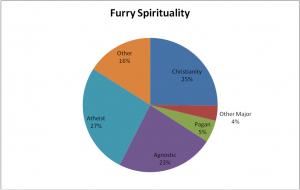

Q6: Are furries spiritual?

The figure below shows that approximately half of the furries in our sample report being either atheist or agnostic. One quarter of furries report Christian beliefs of one form or another. “Other Major” refers to Hinduism, Islam, Buddhism and Shintoism. “Other” refers to all other answers. So we can say that between 35-50% of the furry community reports some form of spiritual belief or affiliation with a religion.

Furry Statistics

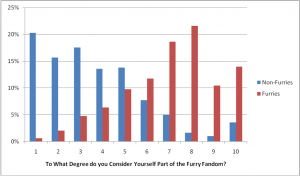

Q7: How do you know the furries in your sample are different from non-furries? Are they “more furry”?

We asked participants, on a scale of 1-10, to what degree they considered themselves to be “part of the furry fandom”. The average score for non-furries was 3.68, while the average score for furries was 7.01. This represents a significant difference between the two groups, allowing us to say that we are in fact dealing with “furries” and “non-furries” (or, at very least, with “more” and “less” furry furries). It also shows that the average furry in our sample identifies with the furry community quite a bit (although we should note that we recruited furries mostly from furry websites. As such, there is likely some selection bias – that is, a tendency to under-recruit less-involved furries).

Q8: How long has the average furry been a furry?

The average furry in our sample reported being a furry for approximately 6.7 years. The average furry in our sample also reported that they first realized they were a furry at the age of 16.2 years, and that they considered themselves a part of the “furry fandom” at the age of 17.5 years. Interestingly, this means that for the average furry there is a 1-1.5 year gap between the time they consider themselves a furry and the time they consider themselves a part of the furry community. This may represent a time of confusion or identity-questioning for furries trying to find a place to fit in or a group of like-minded individuals to interact with.

Q9a: Do furries think they’re human? Are they people who want to be animals?

To answer these two questions we asked furries if “you consider yourself to be less than 100% human” and if “you would be 0% human if you could”. 75.1% of furries said they do not consider themselves to be less than 100% human (in other words, 75.1% of furries consider themselves 100% human), while 24.9% of furries agreed that they did feel less than 100% human. In comparison, 86.8% of non-furries said they felt 100% human and only 13.2% said they felt less than 100% human. As such, we can say that furries are about twice as likely as the non-furry population to say that they do not feel entirely human.

52.6% of furries answered the second question by saying that they would be 0% human if they could, with 47.4% of furries saying that they would not be 0% human if they could. To compare, only 30.6% of non-furries said they would be 0% human if they could. As such, we can say that furries are about 1.7 times more likely than non-furries to report wanting to be completely non-human.

We elaborated on these results by crossing the answers to these two questions to create a “typology” of 4 types of furries, with the following proportions:

- Type I — Feels completely human and does not wish to be non-human: 41.7% of Furries, 64.8% of Non-Furries

- Type II — Feels completely human but wishes to be non-human: 33.4% of Furries, 22.0% of Non-Furries

- Type III — Does not feel completely human, but does not wish to be non-human: 5.7% of Furries, 4.5% of Non-Furries

- Type IV — Does not feel completely human and wishes to be non-human: 19.2% of Furries, 8.6% of Non-Furries

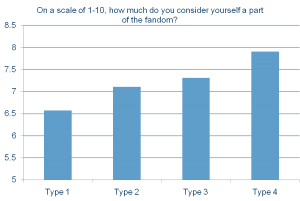

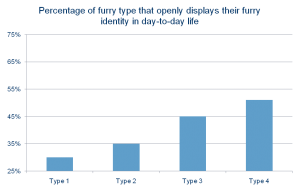

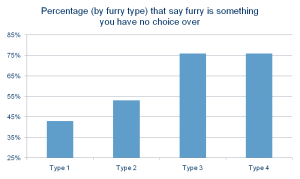

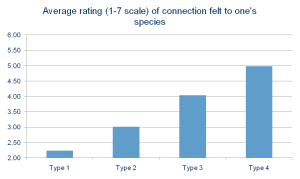

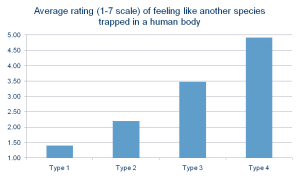

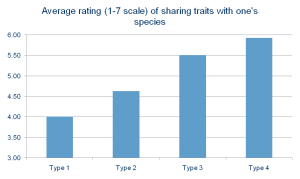

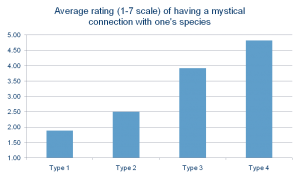

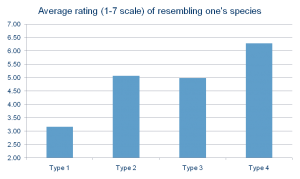

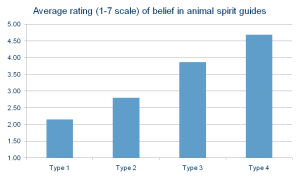

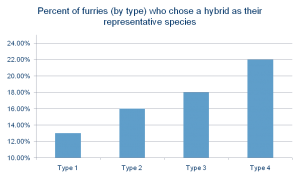

Q9b: You’ve broken furries down into 4 types. Cute. But does it really matter what “type” of furry you are?

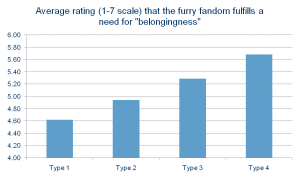

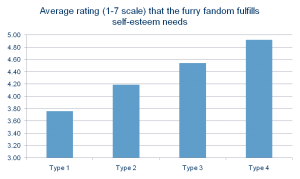

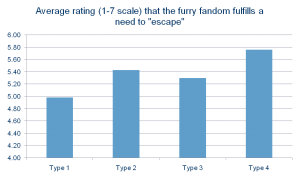

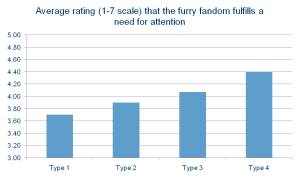

The “type” of furry you are matters: As a person goes from “Type I” to “Type IV”, the following effects were found:

a) Furry type is correlated with how much a person considers themselves to be part of the furry fandom.

b) Furry type is correlated with how openly a person displays their furry identity in day-to-day life.

c) Furry type is correlated with opinions that “furry” is not a choice a person has any control over.

f) Furry type is correlated with seeing the fandom as fulfilling a need for escape (from day-to-day life).

n) Furry type is correlated with the likelihood of choosing a hybrid as one’s representative species.

o) Furry type is related to one’s religious beliefs.

To conclude this answer to Question 9b, the “type” of furry you are DOES matter on a number of important traits. It may be the case that “Type I” furries may be considered “furry fans” in the sense that they are fans of the artwork/ writing/ culture of the furry community, while Type IV furries may represent therians or people for whom furry is not just someone one “is a fan of”, but rather is a way of life, a part of who they are, or is something that serves important social/psychological functions for them.

The effect of furry typology in all of the above figures was statistically significant, even after controlling for the effects of age, gender and (apart from the first figure), the degree to which one considers themselves to be part of the furry fandom.

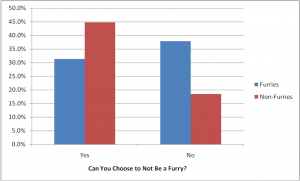

Q10: Is furry a “choice”? Does a person have any control over whether or not they are a furry?

We asked furries and non-furries whether a person had any control/ choice over whether they wanted to be a furry or a non-furry, with the options of “yes”, “no” or “I don’t know”. If you look at the “no” responses, you see that furries were twice as likely (about 38%) to say that furry was not a choice than non-furries (about 19%). Additionally, you can see, looking at just the blue bars, that furries were more likely to believe that furry was not a choice than they were to believe that it was a choice. The reverse was true for non-furries, who were much more likely to believe that furries have a choice to be furry.

Gender and Sexual Orientation

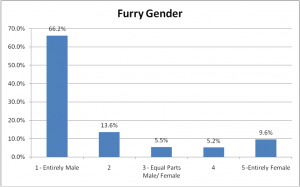

Q11: Okay, we know that there are more biological males than females in the fandom. What about the gender of furries?

It is important to note that biological sex and gender are two very different things. Sex is based entirely on genetics: whether a person has two X chromosomes (female) or an X and a Y chromosome (male), or something else (XO, XXY, etc…). Gender, on the other hand, is what we call “socially constructed”: regardless of what a person’s biological sex is, they can act in stereotypically “male” or “female” ways. What we call “male” or “female” ways of behaving are determined by society as a whole. There is nothing wired into genes that says “boys should play with trucks” or “girls should wear dresses” – statements such as these are taught to us by society. As such, it’s entirely possible possible for a genetically male individual to act in stereotypically “female” ways; in other words, for a biological male to adopt a socially “female” gender identity. The reverse is also true, for a biological female to adopt a socially “male” gender identity.

As such, in addition to asking our participants about their biological sex, we also asked them about their gender identity. The data are presented below, on a scale from 1-5 (entirely “male” to entirely “female”, with varying mixes of “male” and “female” in-between). Other responses were available, including “no gender” and “other”. These responses were relatively rare and are not included in the data below for ease of presentation.

Remember that 84% of furries were biologically male. In theory, if there was a perfect 1-to-1 matching of gender to sex, we would see exactly 84% of the below responses as “entirely male”. Of course, this is not the case – only 66.2% of furries reported an entirely male gender identity. Additionally, in a perfect 1-to-1 matching, we would expect 14% of the population (the biologically female) to report “entirely female” gender identities. Again, this is obviously not the case. Instead, there appears to be a degree of “gender-bending”: at the very least, 25% of furries are reporting a gender identity either more stereotypically female or male than their biological sex. This means that at least a quarter of the furry fandom is comprised of males acting “more female” and females acting “more male” than society would dictate appropriate given their biological sex.

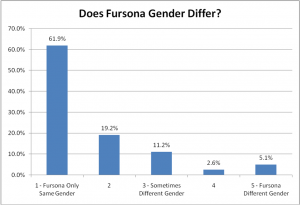

Q12: Do furries pick fursonas that are the same gender as their own?

We asked furries to identify not only their gender, but also to identify the gender of their fursona on a 1-5 scale, ranging from “my fursona is only ever the same gender as I am” to “my fursona is always a different gender than I am” (with varying points in-between, such as “my fursona is usually the same gender as I am, though I am open to trying another gender fursona”). The data suggest that about 62% of furries report having a fursona gender that is the same as their non-fursona gender. This means that approximately 38% of furries are, at very least, open to the idea of having a different-gender fursona. Fully 5% of furries have a fursona that is exclusively of the opposite gender. For these people it remains to be seen whether their fursona is a form of self-expression of a different-gender part of themselves (a way to “play out” another part of their identity) or perhaps a way to experiment with an identity different from their own (some form of role-playing). There is likely truth to both of these possible explanations and others.

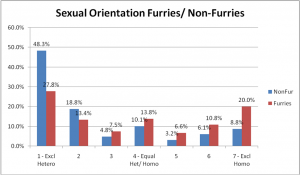

Q13: Are furries “more gay” than non-furries?

We asked participants in our survey (both furry and non-furry) to identify their sexual orientation. In particular, we created a 1-7 scale (from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual, with several possible choices between the two of these such as “predominantly heterosexual with incidental homosexuality” and “equally heterosexual and homosexual”). Additionally, options of asexuality, pansexuality and “other” were available, though they are not presented here for ease of presentation.

The blue bars represent non-furries and the red bars represent furries. Going from left-to-right, the graph is interpreted as going from heterosexual preferences to homosexual preferences. As you can see from the left-most pair of bars, furries are about half as likely as non-furries to report being exclusively heterosexual. Additionally, in the right-most pair of bars, you can see that furries are more than twice as likely to report being exclusively homosexual than non-furries. In sum, the data suggest that about 1 in 4 furries are exclusively heterosexual, 1 in 5 are exclusively homosexual, and the rest are somewhere in-between. It is certainly not the case that furries are an exclusively homosexual group, and the data suggest that it is “slightly more straight than gay”, though the data does support the claim that the furry community is more homosexual than the non-furry community.

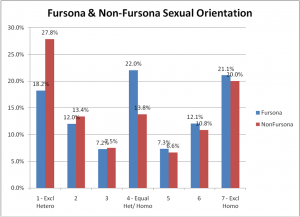

There is a very interesting point to note on some additional data: we asked furries, in addition to their sexual orientation, to identify the sexual orientation of their fursona as well. The data are plotted below, with non-fursona data (red bars, same as the red bars above) plotted alongside the same furries’ fursona data (blue bars).

There is an important trend to notice – looking at the left-most pair of bars, it is apparent that fursonas are significantly less “straight” than their creators. Perhaps most interestingly, however, there is a near-identical increase in “equal parts homosexual and heterosexual” responses for fursonas. This may suggest that for some furries their fursona is more homosexual than they are, and may be a reflection of the fact that homosexuality is still looked down upon in many parts of the world. For these people, it may not be socially acceptable to express homosexual interests; in this case, being able to say “I am not gay, my fursona is” is a way of psychologically distancing oneself from homosexuality. It may also be the case that this is a way of “testing the waters” for furries who may be experimenting with homosexual feelings or who are contemplating coming out as gay. These are only estimates, however, and it is possible that either of these explanations, or neither, may account for these observations. Regardless of the reason why, however, the data do show that, on average, a person’s fursona tends to be “one point” more homosexual than their non-fursona sexual orientation.

Self-Disclosure

Q14: Are most furries “in the closet” about their furriness?

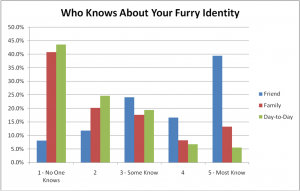

We asked furry participants three questions about self-disclosure – that is, who they have chosen to tell/ inform about their furry identity: how many of your friends know, how much of your family knows, and how much do others in your day-to-day life (job, community, strangers, school, etc…) know? Participants answered on a 1-5 scale from “no one in this group knows” to “most people in this group know”.

Looking at the blue bars you can see, perhaps unsurprisingly, that furries tend to tell their friends about their furry identity more than anyone else. That said, only about 55% of furries said that many or most of their friends knew about their furry identity, with 45% reporting that some or only a few of their friends knew.

The amount of self-disclosure was even lower for family or day-to-day interactions: 40-45% of furries said that no one in their family, work, school or day-to-day life knew that they were a furry. Only about 35% of furries report being out to “some” or “most” of their family about their furry identity, and even fewer made it known at work or in day-to-day life. These data collectively suggest that for many furries their furry identity and affiliation with the furry community is something they keep to themselves or tell very few people about. In another question, we found that only 35.1% of furries reported any sort of outward display of their furry identity in day-to-day life (e.g. “wearing a collar”, “wearing a furry t-shirt”, “drawing furry art in public”, “wearing a tail”, “having furry badges on my backpack”, etc…).

Whether this lack of disclosure of furry identity is due to perceived backlash from the surrounding community/ friends/ family/ work, to a desire to treat it, as some have suggested, “like a fetish” in terms of how you talk about it (e.g. “you wouldn’t talk about an interest in bondage at work”), or some other factor remains to be seen in future studies.

Species Questions

Q15: Why do furries choose the species they do?

There are as many stories for why a person chose the species they did as there are furries in the furry community. It would be next to impossible to collect all of those stories, and even more difficult to present those anecdotes in any kind of meaningful way. Instead, we sought a different approach, asking furries instead to indicate their disagreement or agreement on a scale of 1-7 with a number of possible reasons to have chosen their particular species. While this is by no means a complete list of the potential reasons, it does represent a list of psychologically interesting reasons, and does address some of the more popular reasons. In the future we plan to look at additional reasons for fursona/ species choice.

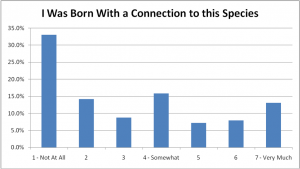

a) I was born with a connection to this species.

It appears that there is quite a bit of variance in responses to this item. 1 in 3 furries disagrees that they have an innate connection to their species, but more than 40% of the fandom agrees with the statement at least “somewhat”.

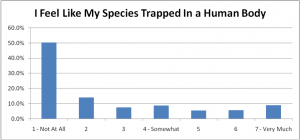

b) I feel like this species trapped in a human body.

Half the furries in our sample completely disagreed with the notion of feeling like their species trapped in a human body, with only about 1 in 3 agreeing with it at least “somewhat”. There seems to be a strong distinction made between furries who disagree with this item and those who do not. It is certainly not the most popular explanation for a furry’s species.

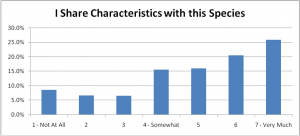

c) I share characteristics with this species.

In general, furries tend to agree with this item quite a bit, with more than 75% stating that it is at least somewhat true that they share characteristics with their species. Interestingly, about 15-20% of furries say that shared characteristics have little to nothing to do with their relationship to their species.

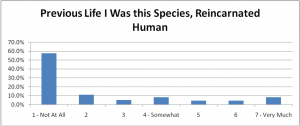

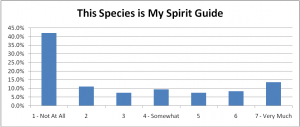

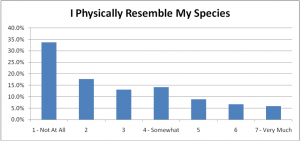

d) In a previous life I was this species (but have since been reincarnated as a human).

The vast majority of furries disagreed with the notion of having been a member of their species in a past life and then reincarnated as human, though for 15-20% of furries reincarnation at least somewhat explains the nature of their relationship with their species.

e) This species is my spirit guide.

A majority of furries disagreed that their species was some form of spirit guide to them. As mentioned in Question 9b, it may be the case that a specific “type” of furry (Type IV) would endorse this item and similarly spiritual items.

f) I physically resemble this species.

In general furries disagreed that their species choice was due to a physical resemblance to their species, with one-third to one-half of furries disagreeing vehemently with this item. One in five furries did cite physical resemblance as an important part of the relationship they had with their species.

Q16: How many fursonas has the average furry had?

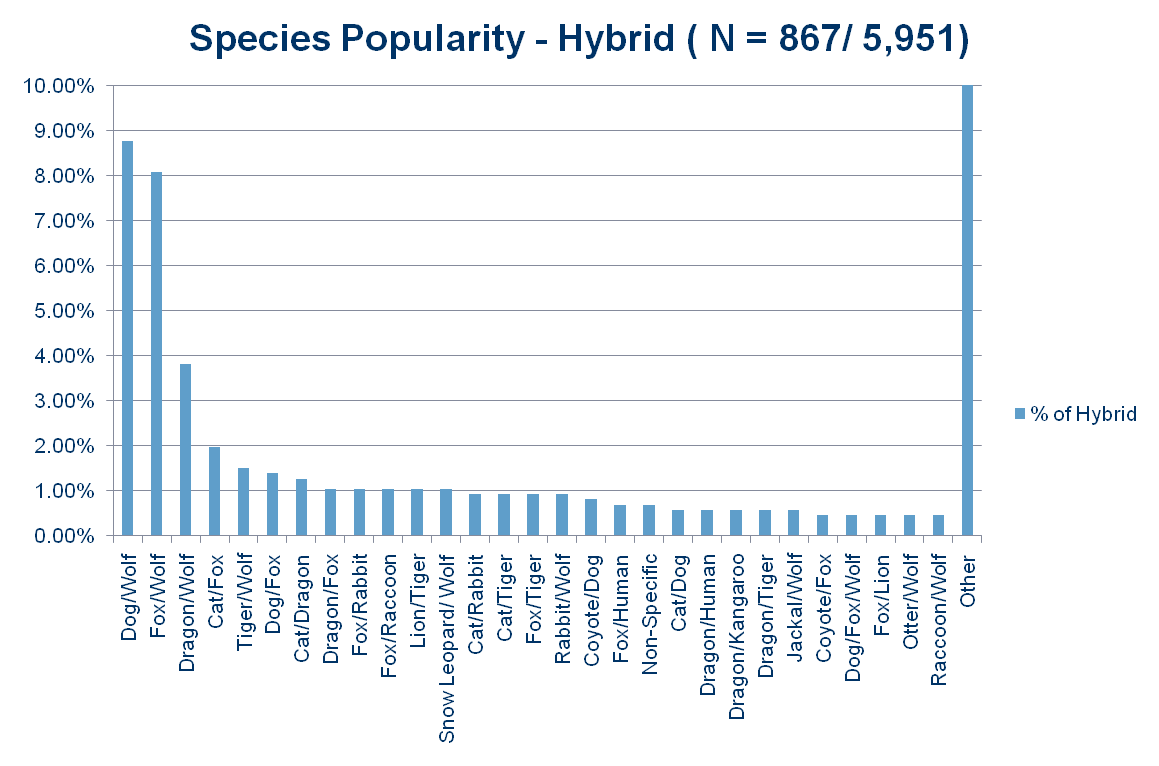

Perhaps some of the most difficult to analyze (but most interesting!) data collected was the responses to the simple question of a furry’s species, be it their fursona species or a species they feel the most connection to. Furries were asked to indicate their most current fursona (if they had one), and to also include any former fursonas. They also indicated hybrids of species where relevant. In total, 5,951 distinct fursonas were included in these statistics. 77.3% of furries has only ever had 1 fursona, while 12.3% report having only ever had two. 6.3% of furries have had 3 fursonas in their life, with the remaining 4% or so of furries reporting 4 or more fursonas in their life.

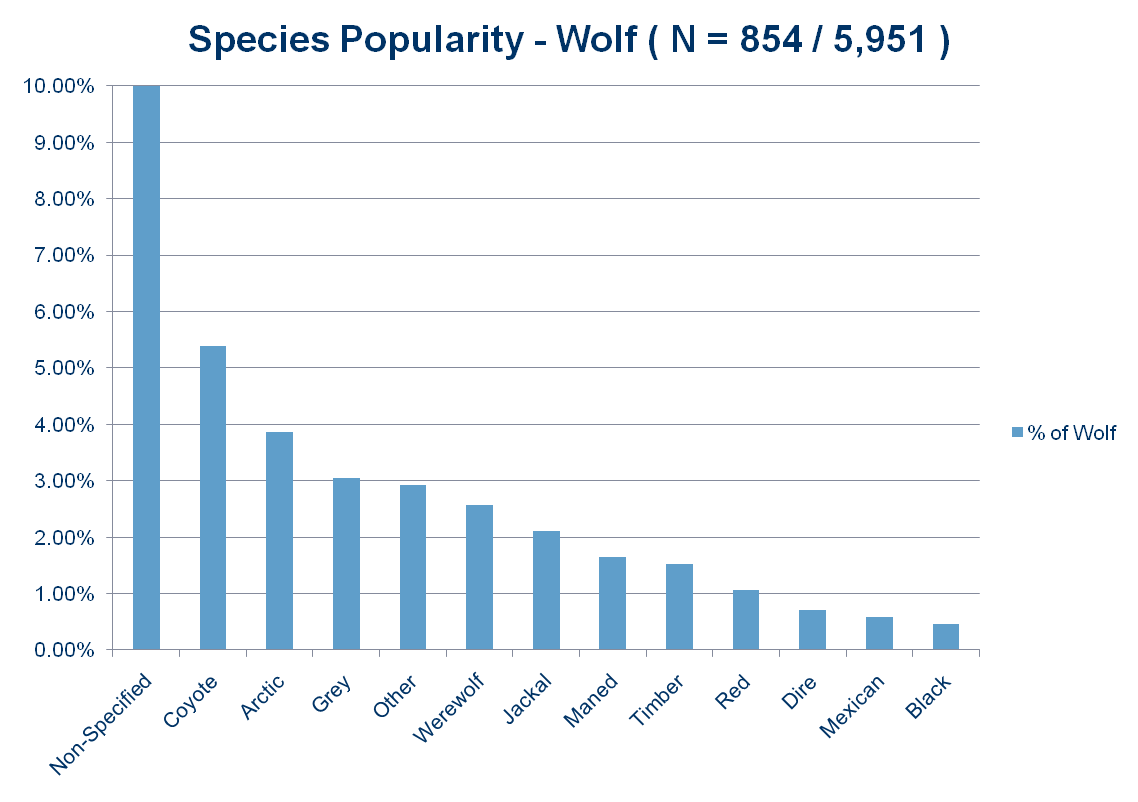

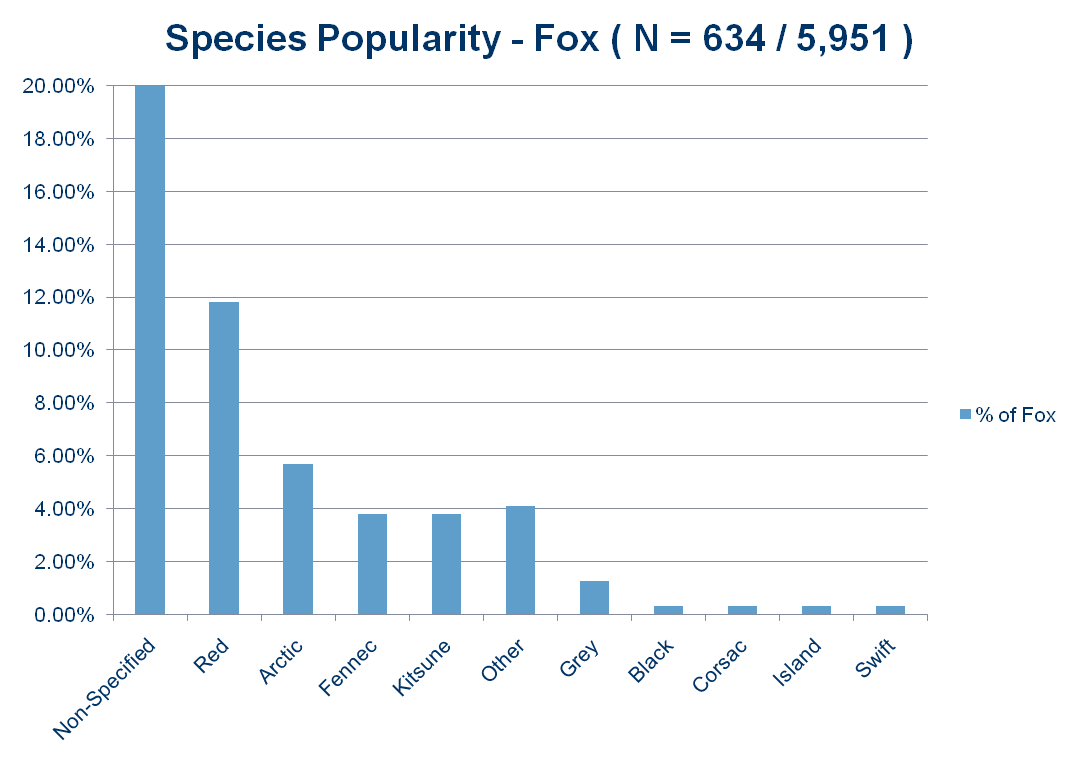

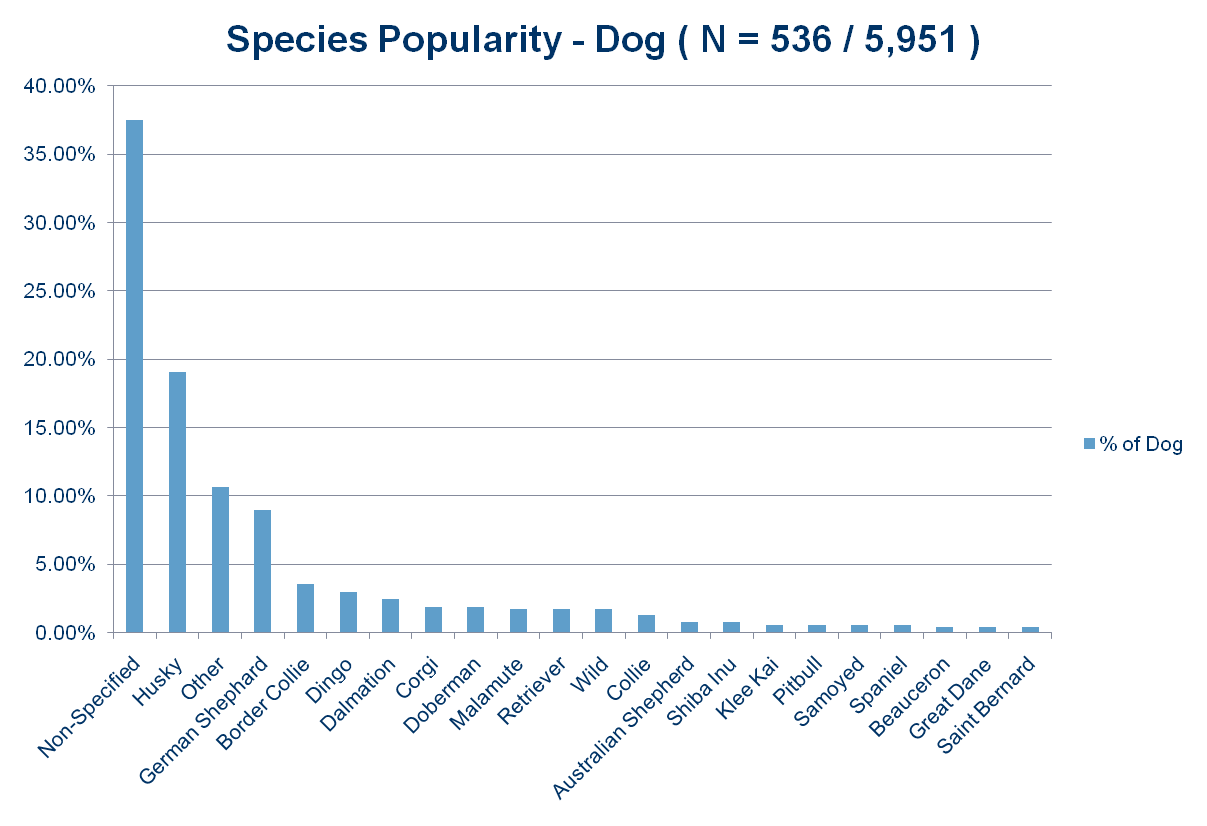

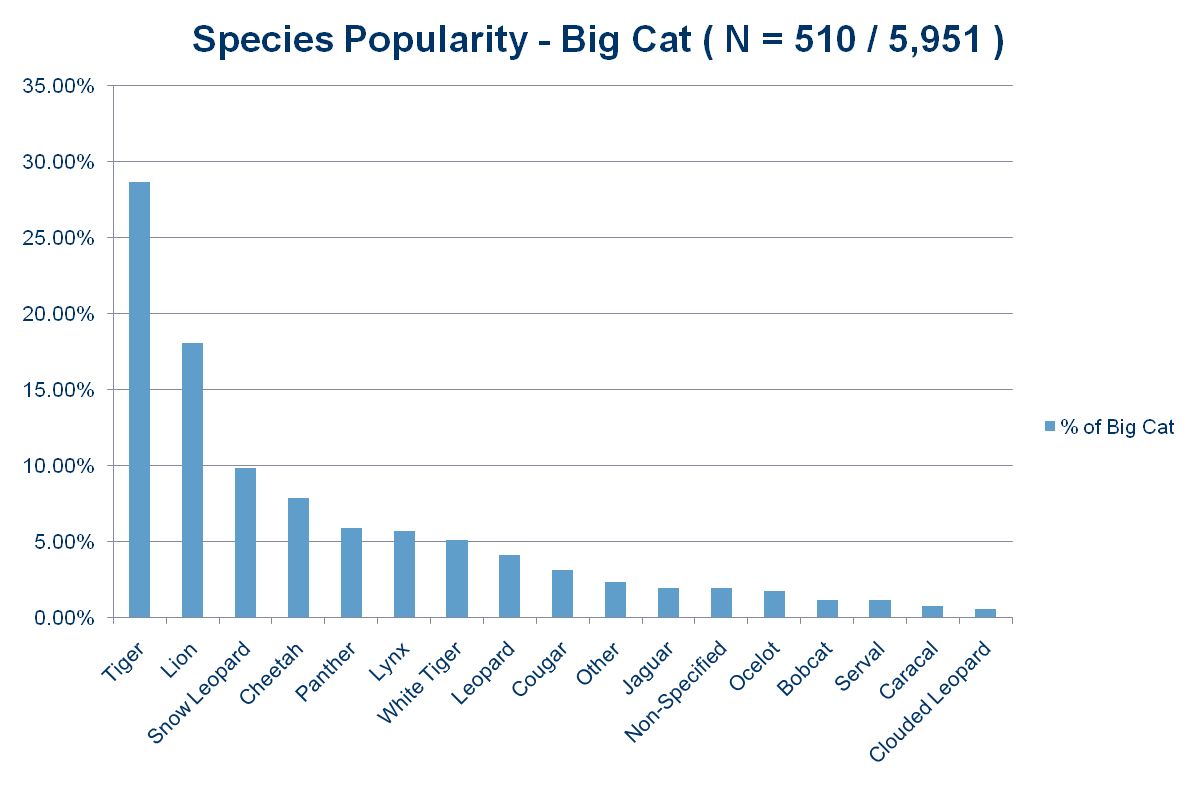

Q17: What are the most popular species?

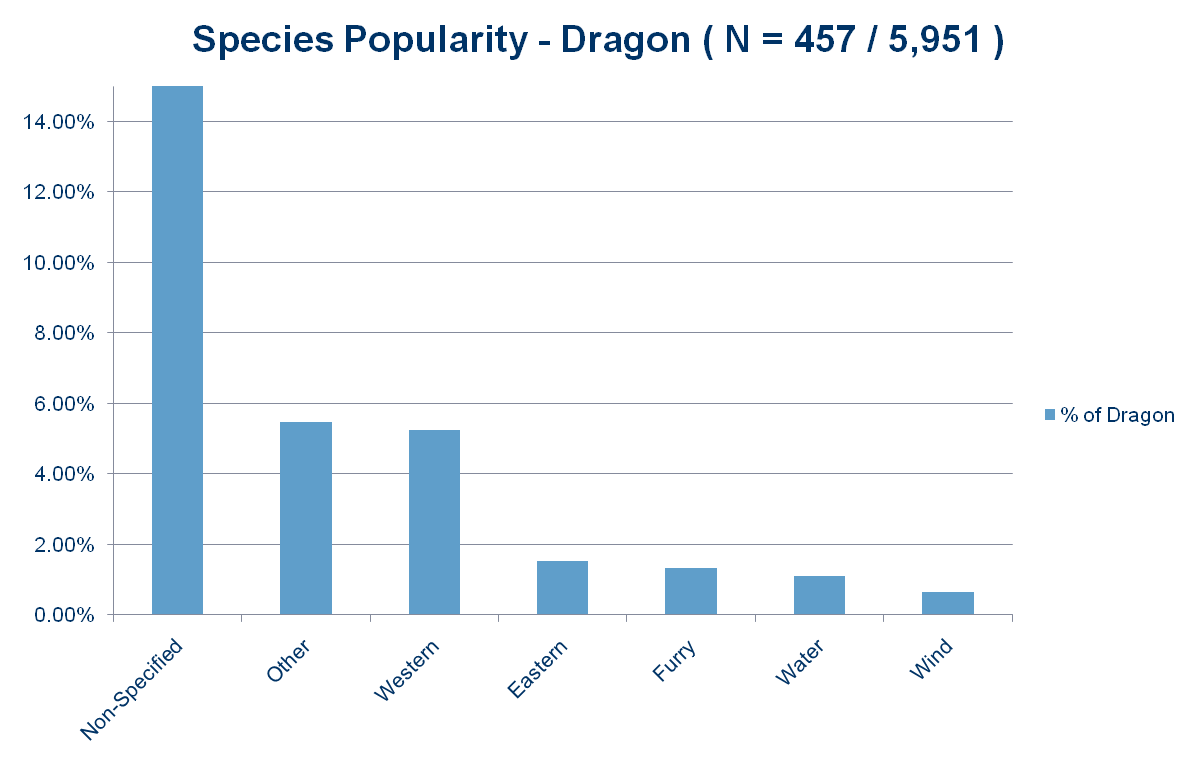

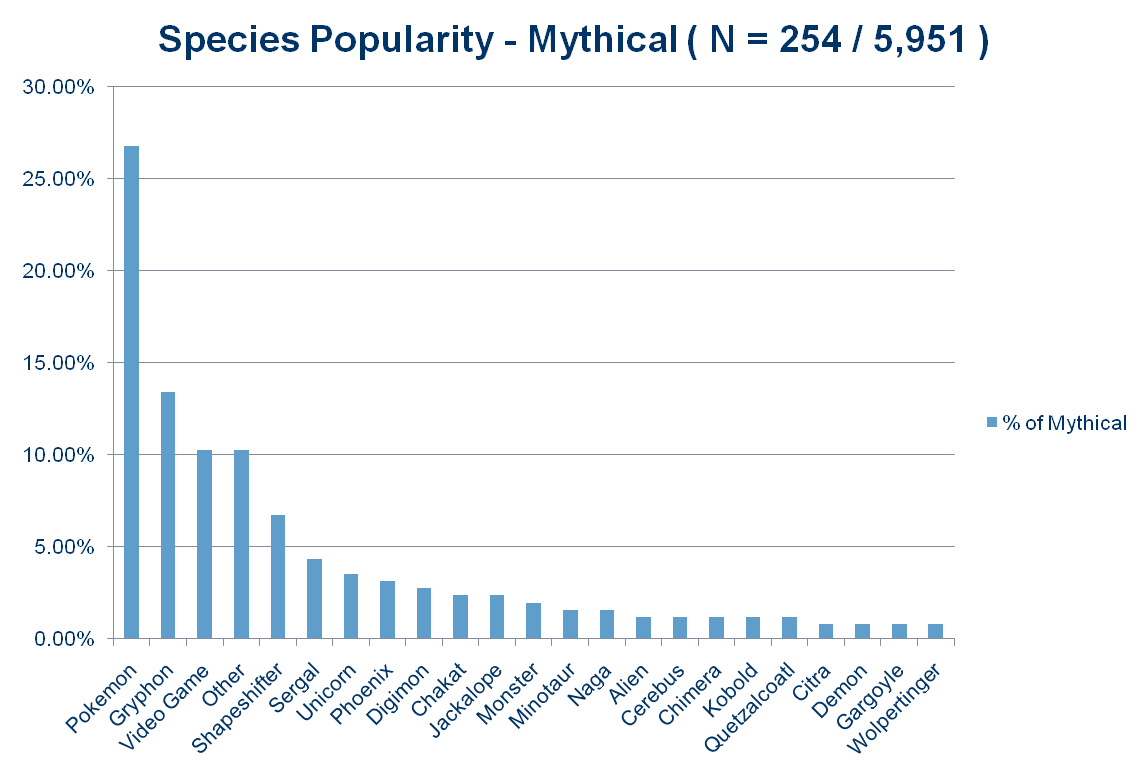

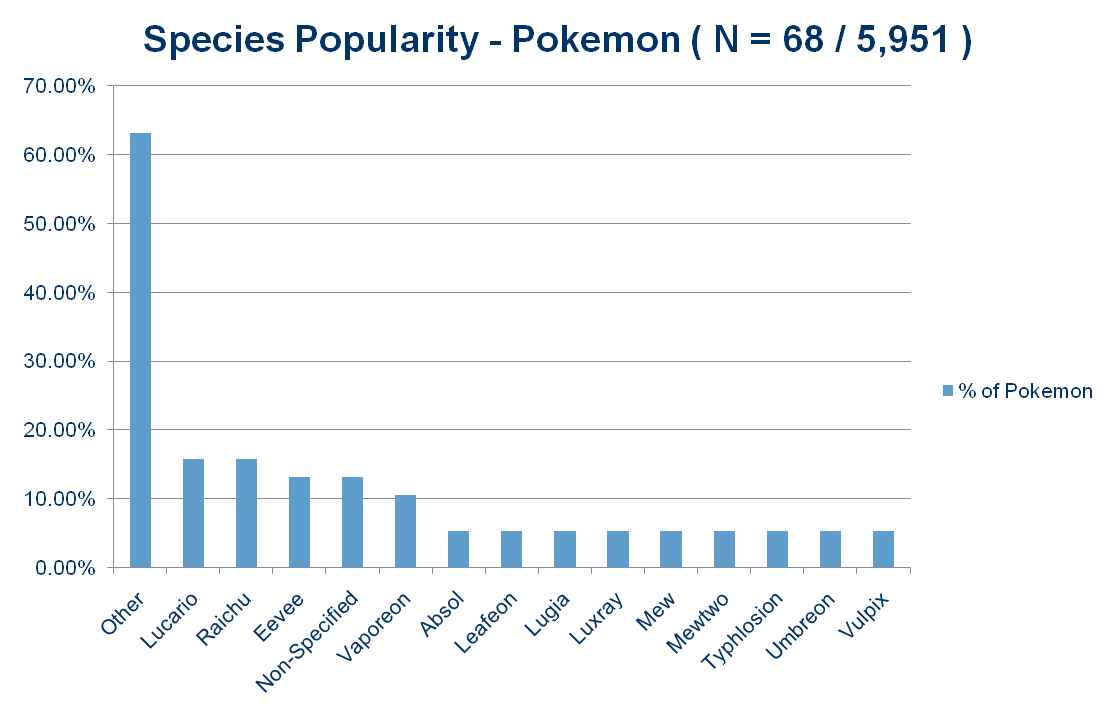

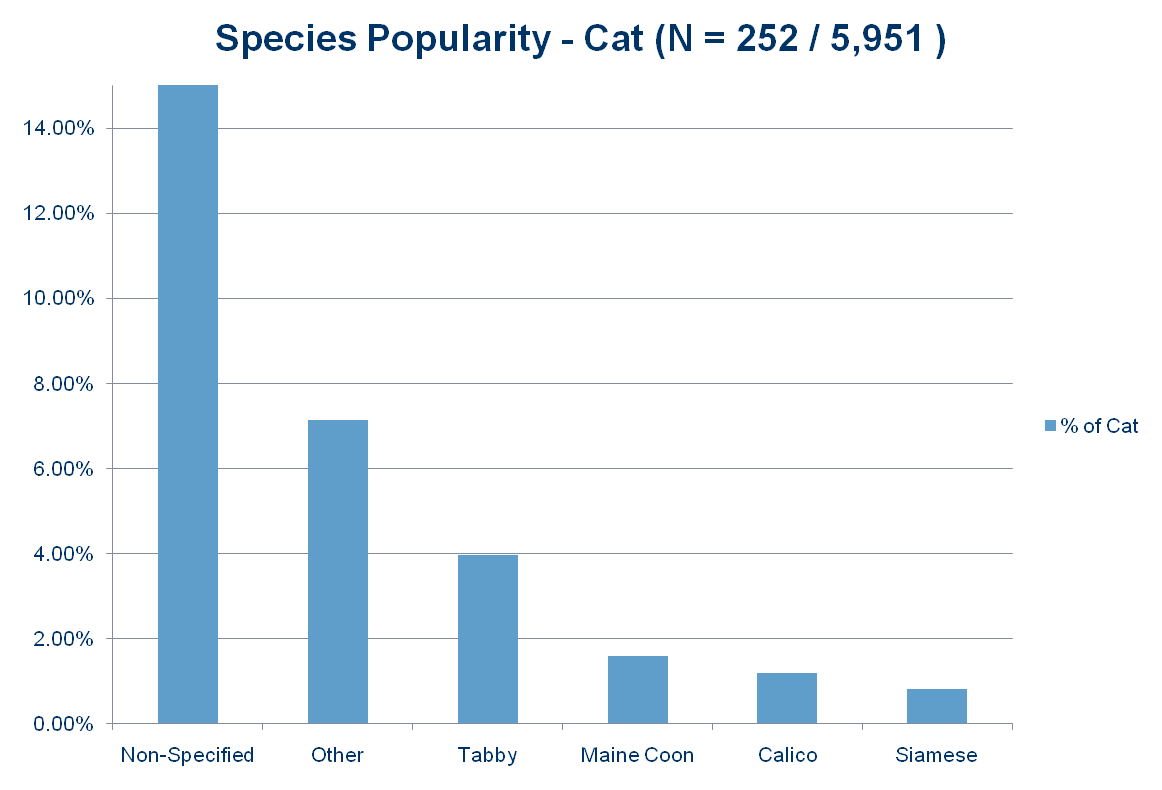

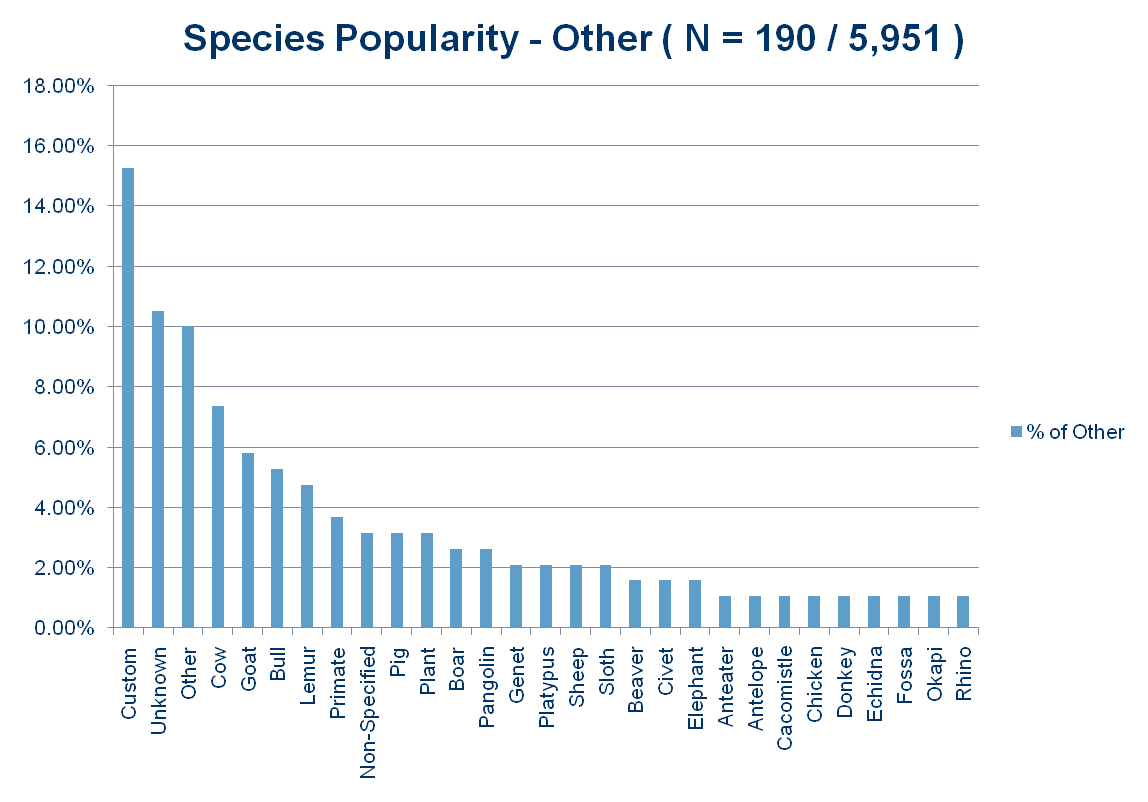

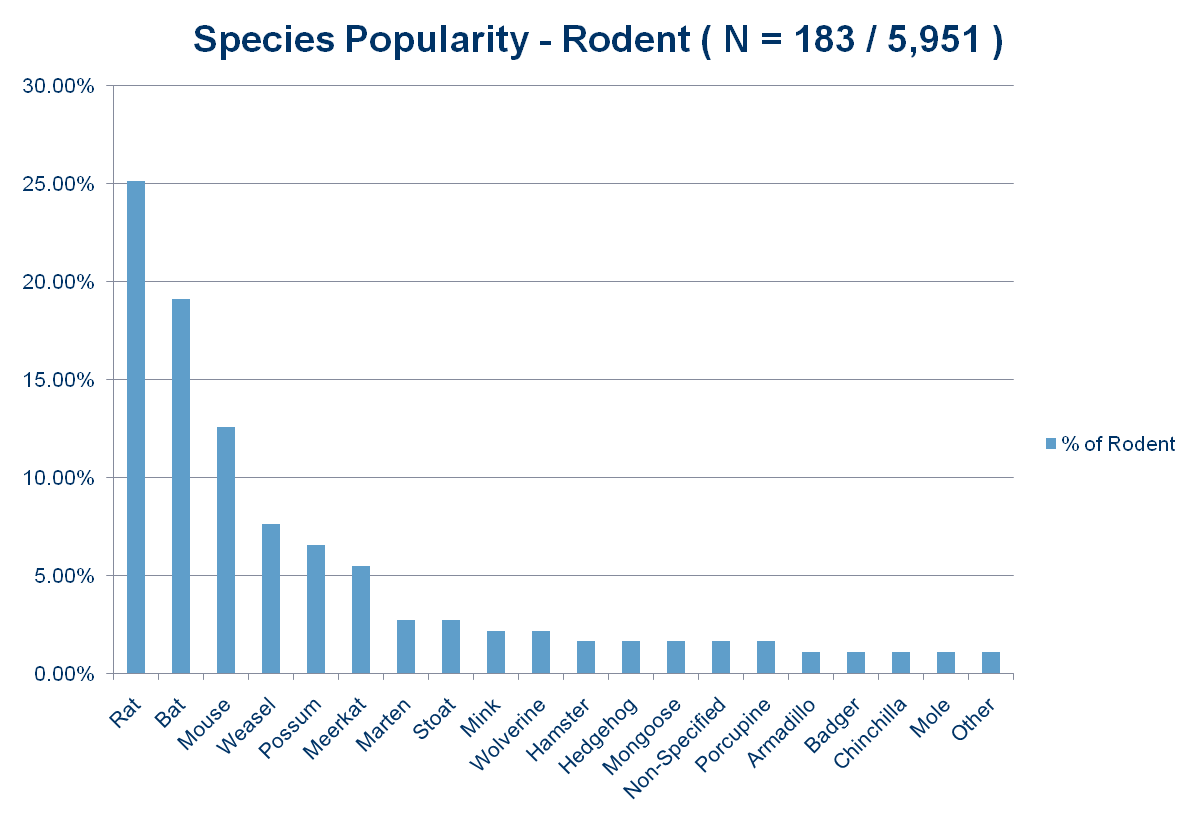

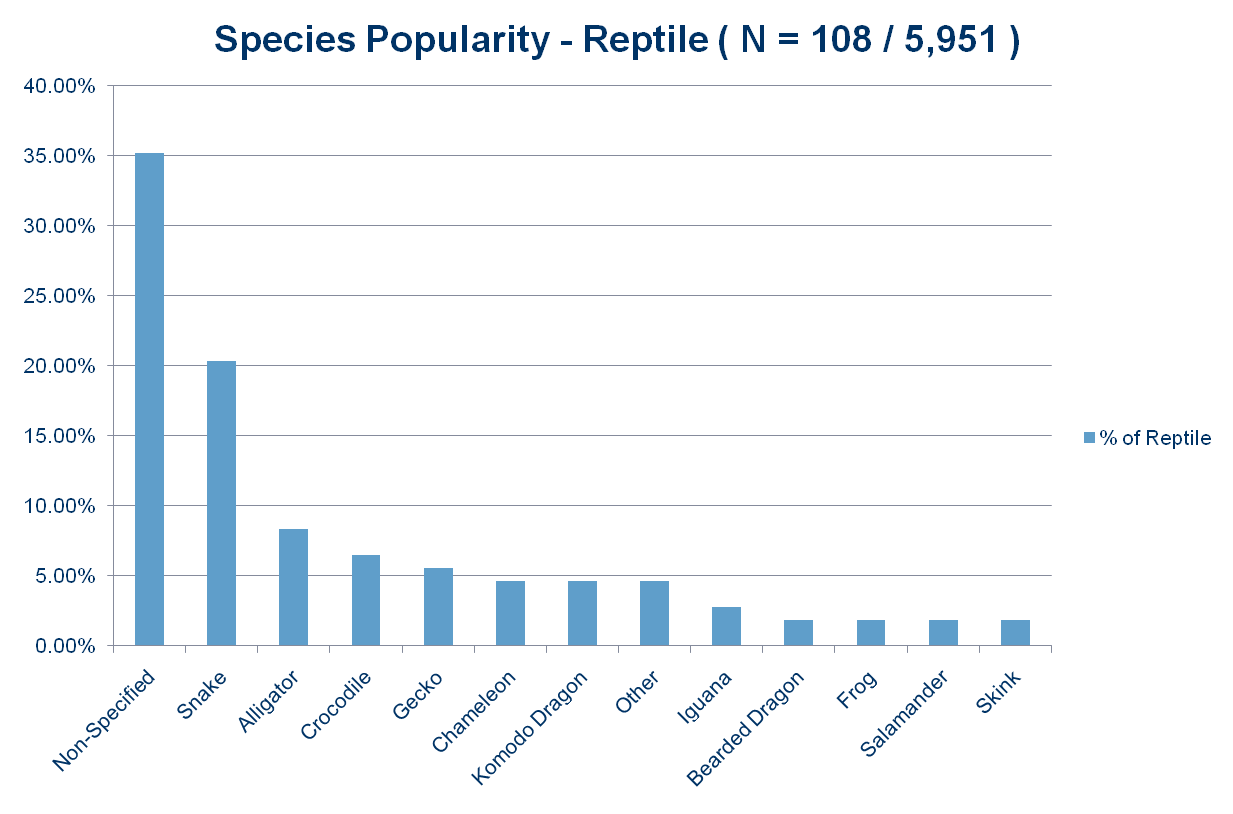

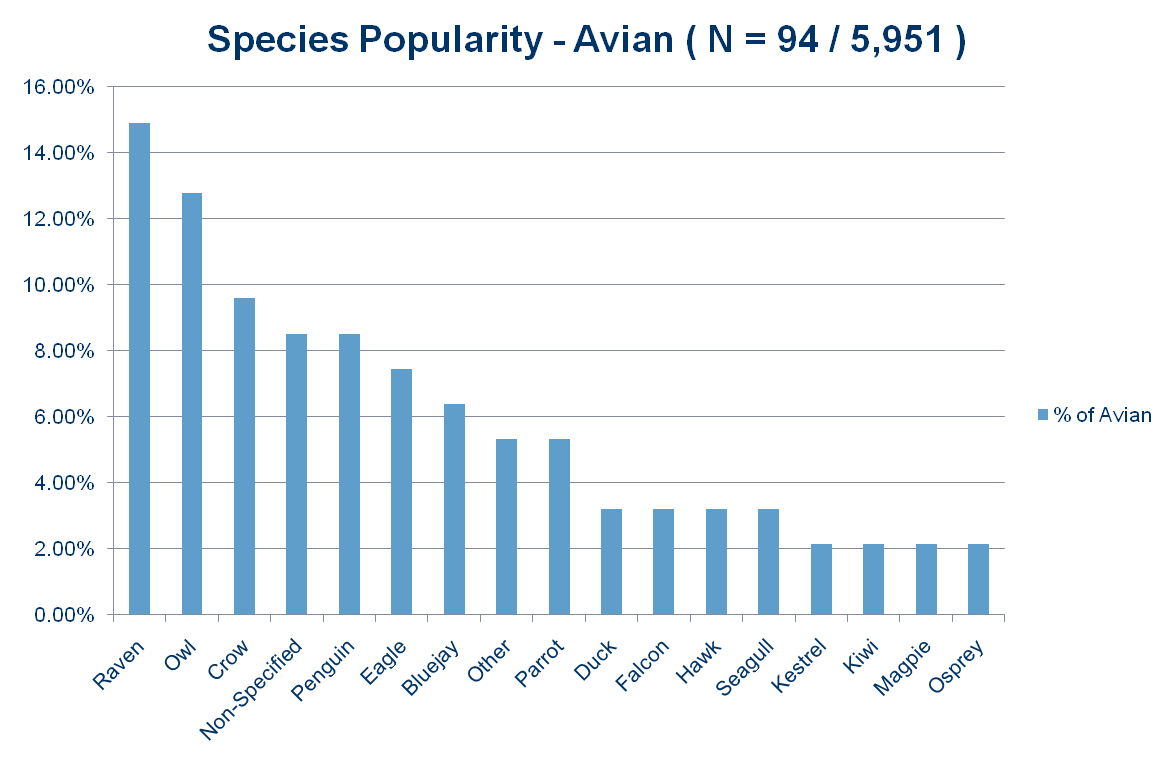

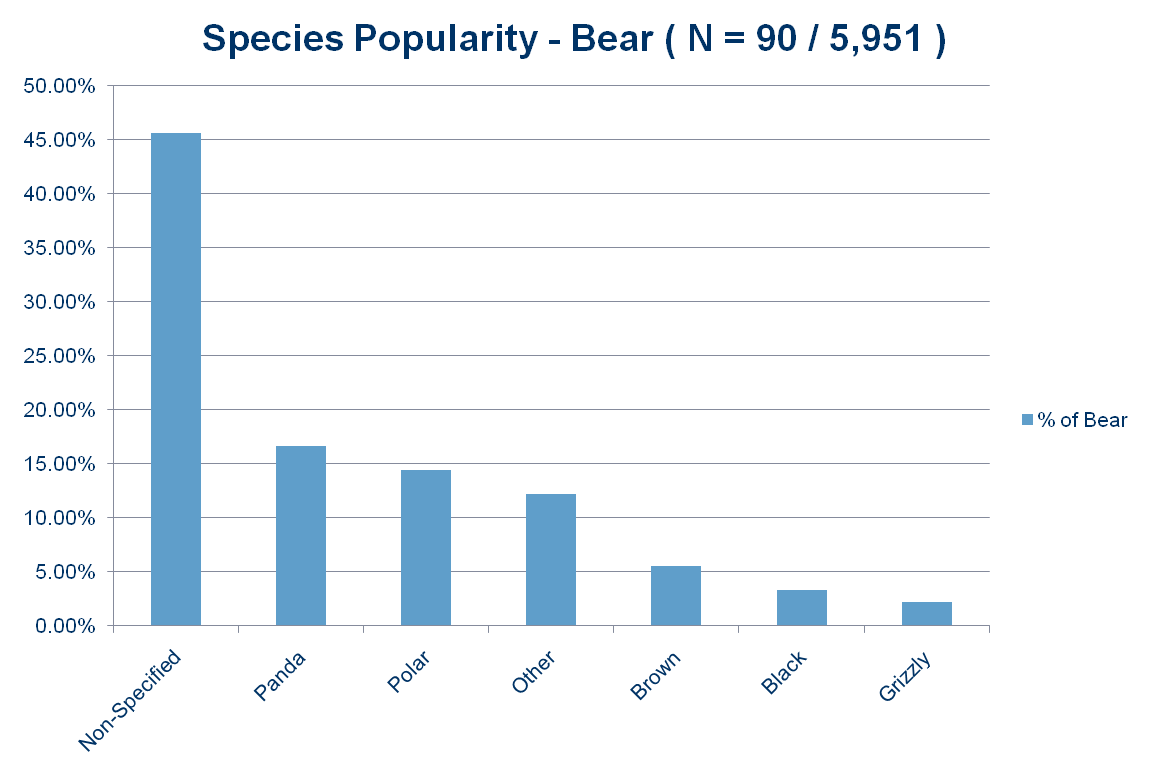

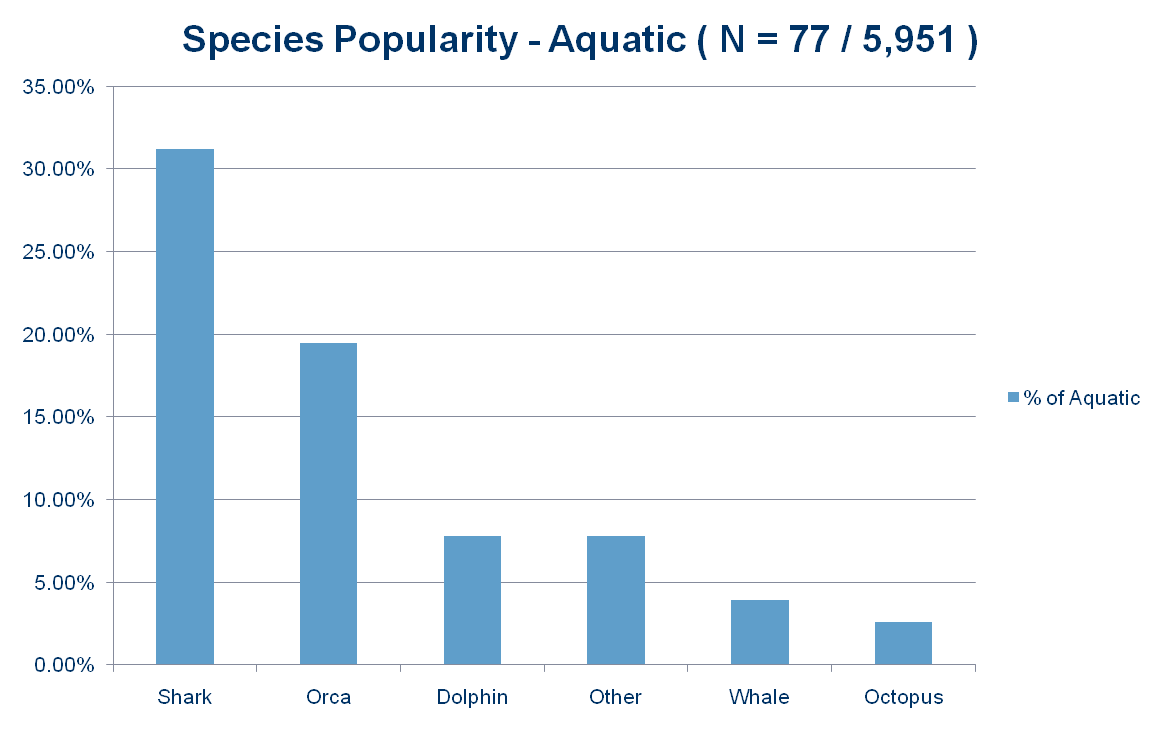

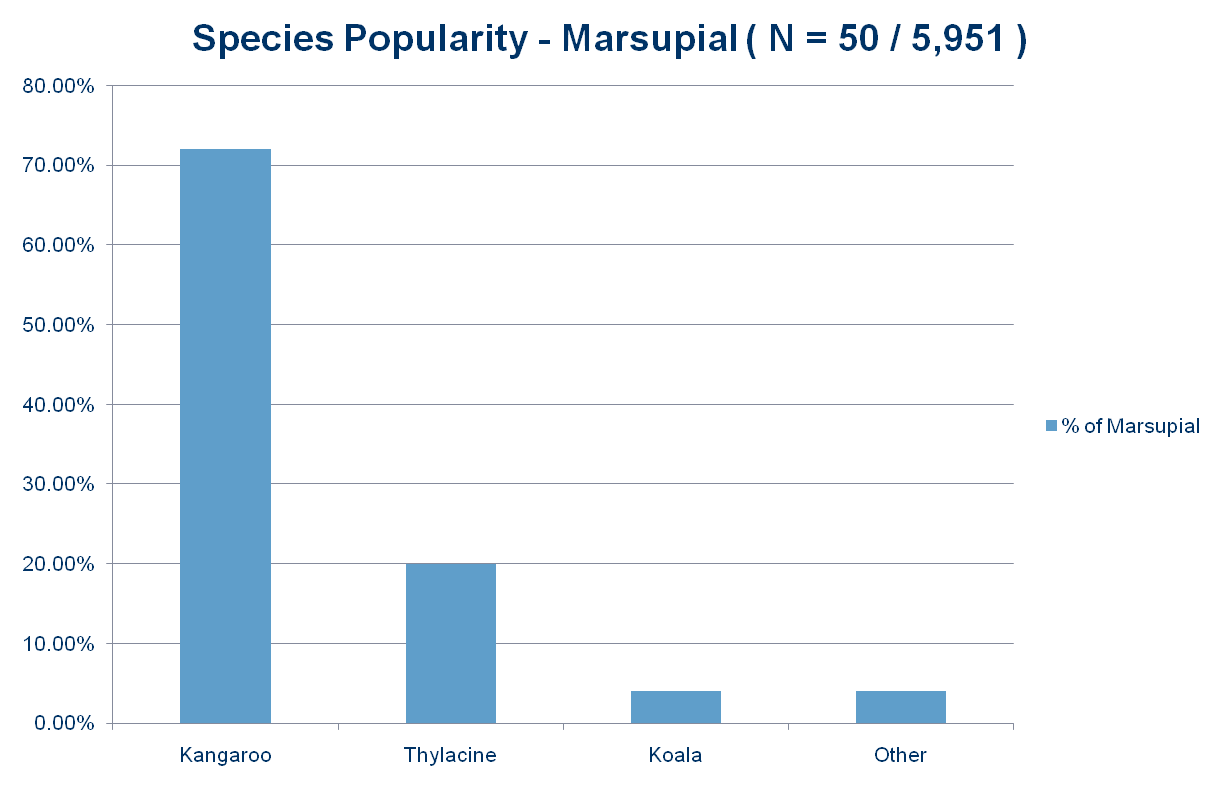

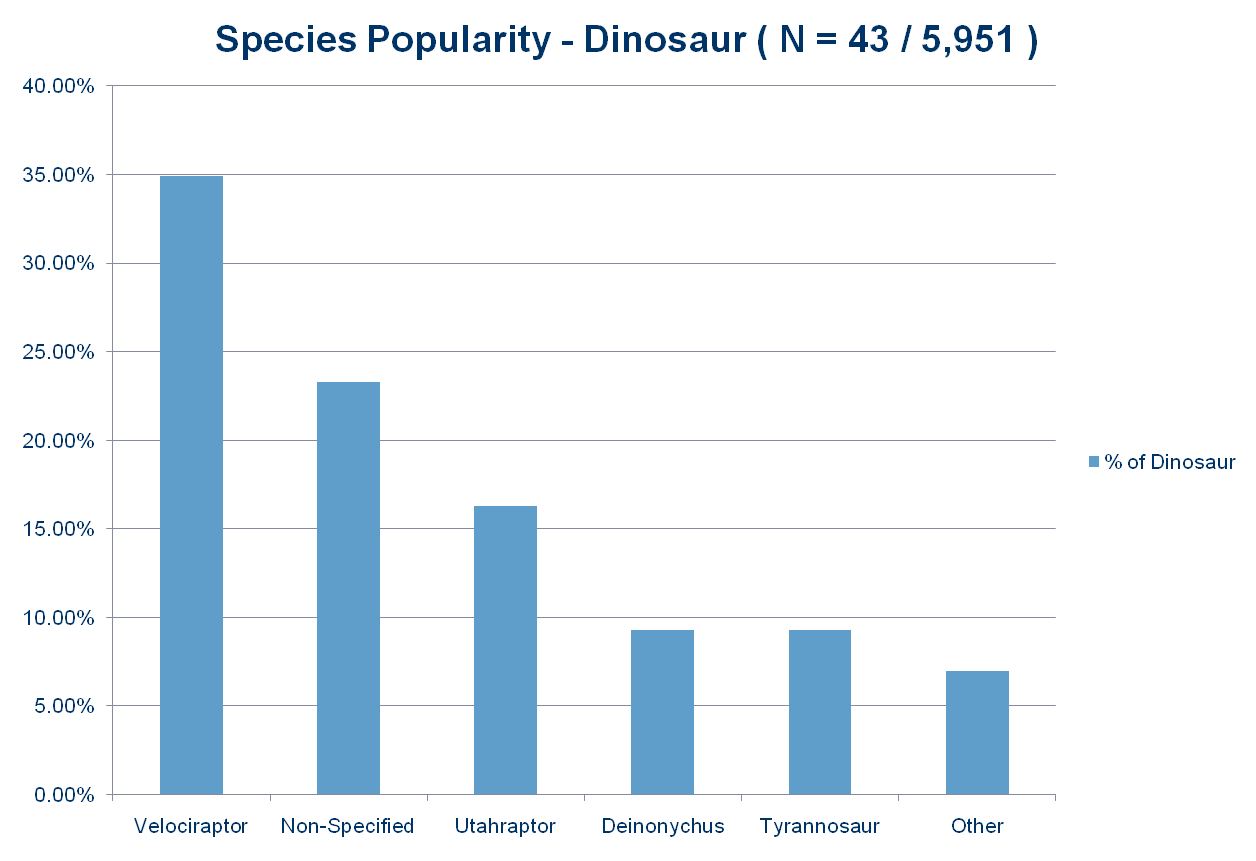

From the dataset described in Q16 we were able to extract and categorize nearly 6,000 distinct fursonas, first by specific species and then into larger, more manageable categories. In all, 852 unique species were identified and subsequently categorized for simplification of analysis. Many of the species listed were unique and, as such, cannot be presented. They fall under “other” categories for the most relevant group in the below figures to protect the identity of those participants.

The data are presented first for all species, and then by-group breakdowns of popular categories. Within category, “unspecified” means that the species was simply identified as the category (e.g. within the “wolf” category analysis, “unspecified” refers to people who just put “wolf” rather than any specific breed/ type of wolf).

Also note that this category breakdown is not meant to reflect biological taxonomy or cladistics, but instead is meant to be a close approximation of how groups of similar species “clustered” (e.g. the authors know that a wolverine and a badger are not “rodents”, but included them in with “small furry mammals” for ease of analysis).

a) All Species

Q18: Did location affect species choice?

The data suggested that there were no real differences in species choice based on location. The only significant differences occurred for for dragons and for big cats – dragons and big/ wild cats were significantly (statistically) more likely to be chosen by European furries than by North American furries—and for marsupials, which were much more likely to be picked in Australia than in other parts of the world.

Q19: Does species choice matter?

Unfortunately, due to length considerations we were unable to include personality measures on this survey. As such, we were unable to correlate species choice with different personality variables to see if a person’s personality influences the species they select.

That is not to say, however, that we did not find significant effects of species choice on other interesting variables. For example, one set of measures we collected was to have participants rate seven different species (dragon, dog, cat, tiger, lion, fox and wolf) on six different traits: aggression, masculinity, femininity, sociability, fun-loving and admirability. We then looked at people whose species was one of those seven species and compared their ratings of that species to others’ ratings of that species (for example, if you were a fox, we compared your ratings of foxes to others’ ratings of foxes, if you were a wolf, we compared your ratings of wolves to others’ ratings of wolves, and so on). The results? Regardless of what species you were (whether a dragon, fox, wolf, etc…), you were more likely to see your particular species as more masculine and feminine than others did (research suggests this is a positive thing). You’re also more likely to see your particular species, whatever it is, as more sociable, fun and admirable than others. You’re also more likely to see your species as less aggressive than others do, even if it’s a particularly aggressive species (like a lion or a dragon). In short – furries are biased to see “their” species better than others do, regardless of what the stereotypes of that species may be. Far from being something “obvious” or “unimportant”, this may suggest that by identifying with a species held in such a positive light may serve a useful self-esteem bolstering function for furries. The details of this will have to be studied in future studies.

In addition, there is some preliminary data suggesting differences between furries who pick certain species over others. For example: those who select hybrids and dragons as their particular species tend to, more than average, report stronger identification with the furry community and report that they use the furry fandom more for a sense of belongingness and self-esteem than do furries of other species. Additionally, hybrids are more likely to be a Type IV furry than other species (that is, a furry who believes they are less than 100% human and who would be 0% human if they could). Finally, it seems that females are more likely to choose hybrids and dragons as their species than are males.

Reason for Being in the Furry Community

Q20: Why are furries really furries? Is it for attention? Sex? Self-expression? Something else?

There are numerous reasons to participate in the furry community, and if you were to ask furries why they are a part of the furry community, you would no doubt get dozens, even hundreds of possible explanations. Some of the researchers, however, think that being a part of the furry community/ fandom serves the same psychological functions as belonging to any community does: the need to belong, self-esteem needs, entertainment, attention, even a psychological need for sex. This idea states that while the content may be radically different between belonging to the furry community and, say, a sorority or a group of fans of a sports team or even a science fiction fandom, these groups and others serve the same kinds of psychological needs. To test this, we asked furries to identify how much they agreed or disagreed with a number of possible explanations for their participation in the furry community.

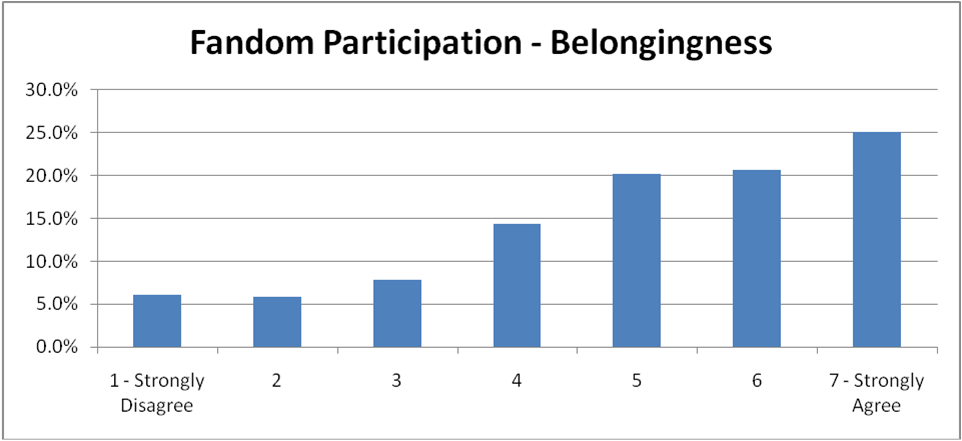

a) A sense of belongingness.

While about 10-20% of furries may disagree to some extent, it seems that, for the most part, furries tend to agree that being a part of the furry community provides a feeling of belonging to a group larger than oneself, a very important social need.

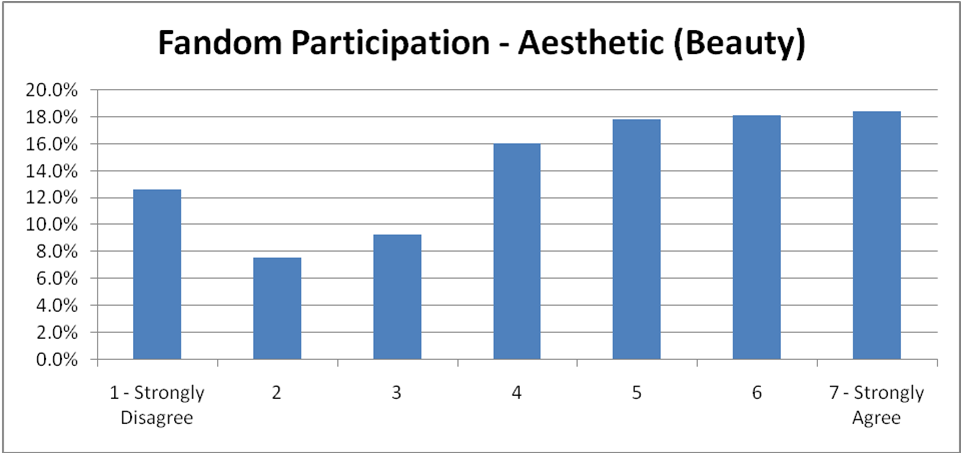

b) Aesthetic/beauty

There appears to be some polarization on the issue of aesthetic/ beauty: about 50% of furries agree that being a furry provides a sense of beauty and aesthetic to their lives (most likely in reference to the art, writing or other creative works of the fandom). The spike on the left side of the figure, however, suggests that 10-20% of furries disagree vehemently with the idea that beauty has anything to do with their participation in the community. This may represent therians or others for whom artwork is not the main draw of the community but rather the opportunity to be with like-minded individuals who identify with animals. Future research will help to test this hypothesis.

c) Self-esteem

There is a lot of disagreement among the fandom about whether being a furry contributes to a person’s self-esteem. For many furries it seems that participation in a community of like-minded individuals is beneficial to their self-esteem. However, for almost as many furries the opposite is true – participation in the furry community may be detrimental to their self-esteem. It’s possible that these are furries who feel that the outside world looks negatively upon furries, and so association with the furry fandom may be a source of stigma for them. Future research will help to test this hypothesis. It also seems that many furries are undecided or ambivalent about whether or not their participation in the furry community is good or bad for their self-esteem.

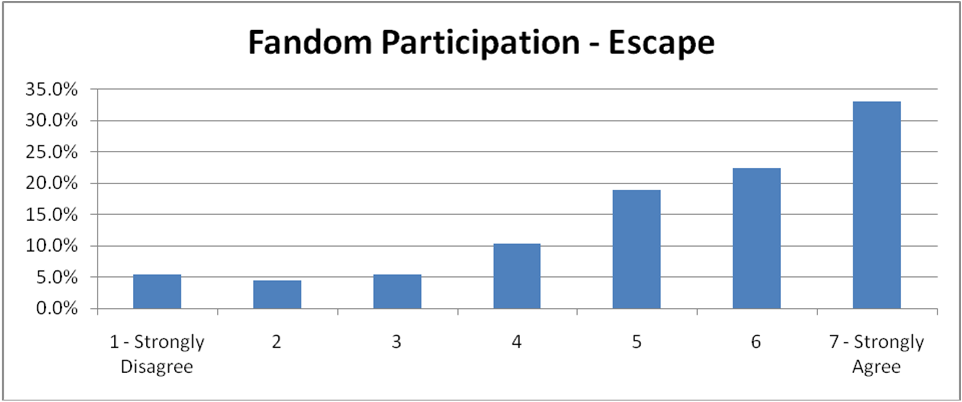

d) A chance to “escape”

There is quite a bit of agreement from the furry community that being a furry allows a chance to escape the routine, possibly “boring” nature of day-to-day life. Nearly 75% of furries agreed at least somewhat that participating in the furry community allowed the chance for escapism. This seems to be a popular reason for participation in the furry community.

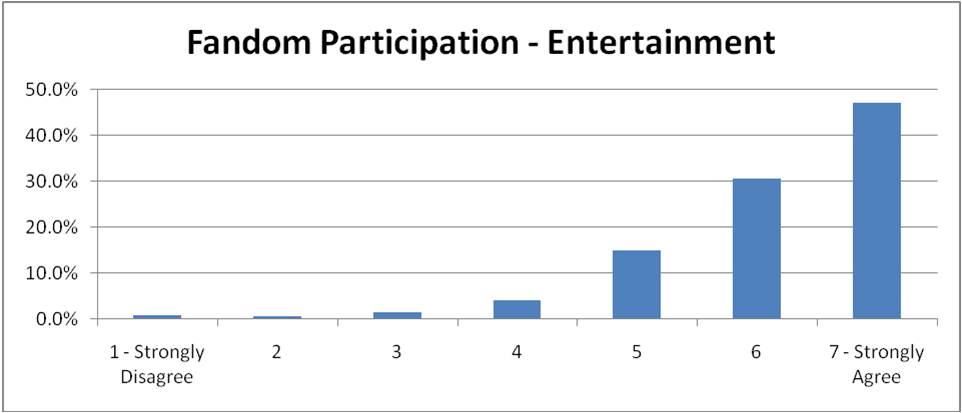

e) Entertainment

There is little disagreement from furries about the fact that being a furry is fun, with nearly 90% of furries agreeing at least somewhat that being a furry serves entertainment purposes. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that many furries consider the fandom to be a leisure/recreational activity. It is important to note, however, that there are a small percentage of furries who say that their participation in the fandom has nothing to do with entertainment.

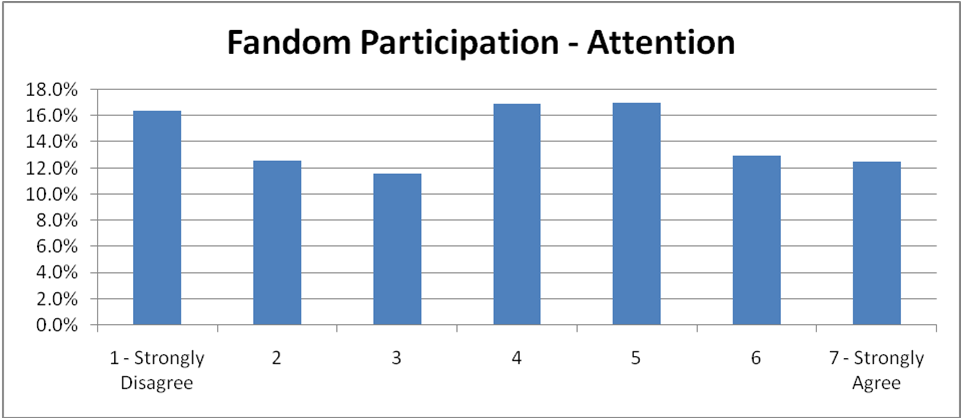

f) Attention

Some stereotypes of furries claim that they are people who crave attention. As you can see from the figure below, this is not necessarily the case. Furries tend to disagree about whether or not getting/seeking attention is an important part of being a furry, with nearly 30% of furries claiming quite vehemently that attention has nothing to do with why they are a furry (while 25% of furries say just the opposite, that attention is an important part). Future analysis/research questions may look at differences between the furries who say attention is important and those who say it is not important, to see how else they differ from one another.

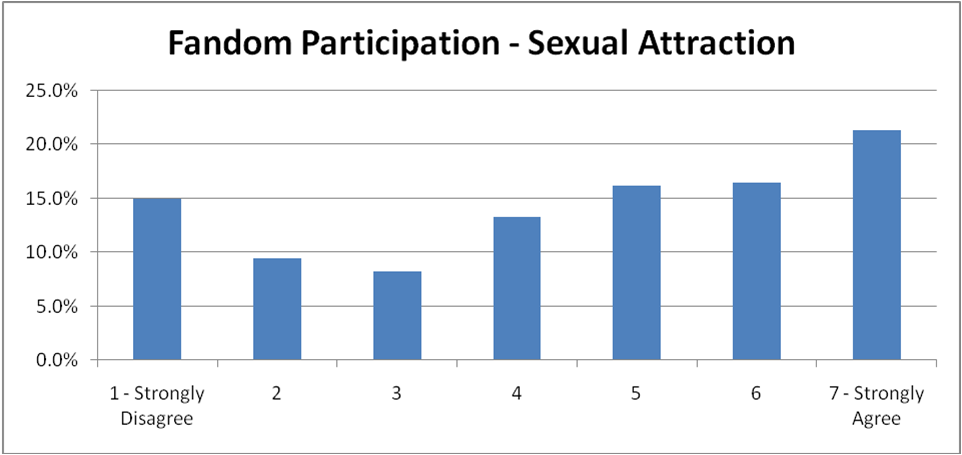

g) Sexual Attraction

One of the questions furries (and especially non-furries) seem most interested in: is the furry fandom about sex? As you can see from the figure, there is a bit of disagreement within the fandom. While one-quarter of the fandom states quite vehemently that sexual attraction has little to nothing to do with their furry activities, one-third of the fandom says just the opposite – that sexual attraction to the content in the fandom is an important part of their furry participation. It seems to be a polarized issue within the fandom, likely made worse by the fact that negative media attention has focused primarily on the sexual aspects of the fandom, possibly contributing to the vehement opposition of many furries to the notion of sex within the fandom. Further research on furry sexuality will hopefully explain these results.

Furry Well-Being

Q21: Are furries “messed up”? People with low self-esteem/other problems?

There is a natural tendency for people to moralize statistical deviance, accounting for differences by condemning it as morally wrong or by claiming there’s something “not right” with people who are different. It serves a number of protective functions for people, including preserving self-esteem and maintaining a positive self-image in the face of potentially challenging or threatening information to the contrary.

As such, there seems to be a tendency for people (furries and non-furries alike) to assume that there is “something wrong” with furries. Some seek psychological explanations, suggesting that furries may be people with developmental problems or conditions such as autism. Others tend to seek situational explanations for furry behavior, claiming that furries must be the product of a broken childhood or some kind of tumultuous, friendless, socially awkward childhood.

At first glance it may seem to the layperson that there is truth to this—if you ask furries whether they were picked on in school or whether they would describe themselves as “not popular”, many furries would agree with this description. It is critical, however, that we not fall into the trap of assuming that this somehow “explains” the behavior of furries. Why? Ask anyone, furry or not, whether they would describe their childhood as “normal”, and you’re likely to get the same answer—”no”. Most people, furry or not, are likely to describe themselves as “socially awkward” or “unpopular”, or as having events in their childhood that could be described as tumultuous. These are not unique to furries, and thus are unlikely explanations for the nature of furry behavior.

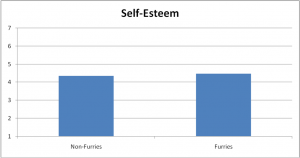

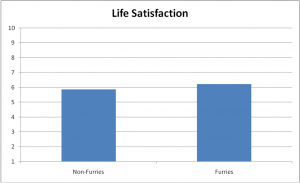

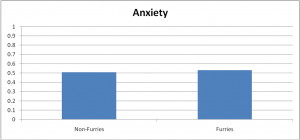

In fact, it may even be wrong to try and “explain” furries in terms of “what’s wrong with them” in the first place. The data below compare furries to non-furries on three different measures of psychological well-being: self-esteem, life satisfaction and anxiety. It’s important to note that there were no statistically significant differences between furries and non-furries on any of these measures. While one has to be careful when interpreting non-differences, we can say that the data we have so far do not indicate that there is anything “wrong” with furries that needs to be explained. Furries may differ in a number of psychologically interesting and important ways from non-furries, but the difference is not psychological dysfunction.

Recent Comments