INTRODUCTION

This webpage outlines the findings of the study “Social Connection through Creative Community: An Ethnographic Study of Autism in the Furry Fandom.” The report is intended to provide information and recommendations to organizers of furry conventions and related events about the participation of people on the autism spectrum at furry conventions and the fandom more broadly, along with some recommendations for how to support that participation.

This report is divided into 3 main sections: “What is autism,” “What Motivates People on the Autism Spectrum to Participate in the Furry Fandom?” and “Barriers to Participation and Recommendations.” If you wish to skip straight to the last section, click here.

What is autism?

The autism spectrum is extremely broad, and what it means to be “on the spectrum” (or to “have autism” or to “be autistic”) means very different things for different people. However, a few things can generally be said to be true about autism. It affects people from very early on in life and continues to affect people for their entire lives, though the way autism affects any given person may change a great deal over time. It tends to affect people in three main areas: their social interactions and relationships; a preference for routine, repetition, or sameness; and differences in sensory sensitivities, ranging from seeking out certain sensory input (oooh, shiny!!) to avoiding certain kinds of sensory input (ugh, florescent lights!). Autistic author Nick Walker defines autism as follows:

Autism is a genetically-based human neurological variant. The complex set of interrelated characteristics that distinguish autistic neurology from non-autistic neurology is not yet fully understood, but current evidence indicates that the central distinction is that autistic brains are characterized by particularly high levels of synaptic connectivity and responsiveness. This tends to make the autistic individual’s subjective experience more intense and chaotic than that of non-autistic individuals: on both the sensorimotor and cognitive levels, the autistic mind tends to register more information, and the impact of each bit of information tends to be both stronger and less predictable.[…] Autism produces distinctive, atypical ways of thinking, moving, interaction, and sensory and cognitive processing. Neurodiversity: Some Basic Terms & Definitions, 2014

Many people on the autism spectrum thus become overwhelmed in highly stimulating, chaotic environments, and may seek quiet, order, or routine as a refuge. People diagnosed with autism also tend to have a range of differences in the ways their brains process information: for example, some have difficulty recognizing faces; some process verbal or auditory information more slowly; some are extremely sensitive to visual patterns. People on the autism spectrum often have difficulty displaying and interpreting nonverbal social cues, such as body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions, and may have trouble with non-literal social communications such as sarcasm. As a result, many have a harder time forming and maintaining social relationships, and may struggle to navigate school, get and keep a job, and find their place in a wider social community. Social isolation poses a significant threat to their quality of life.

What is the connection between autism and the furry fandom?

While people on the autism spectrum often struggle to find a place where they belong, some find community, connection and friendship in creative cultures that are organized around shared interests. The furry fandom is one example. According to survey data from our research team, 10 – 15% of furries self-identify as being on the autism spectrum – a number that includes those who are formally diagnosed with autism, those who feel that they are on the spectrum despite not having been formally diagnosed, and those who are unsure whether they agree with the autism diagnosis they have received. For many of them, the furry fandom provides an important source of social connection, support, and fun.

About the research project

We were interested in what the furry community has been doing to create an inviting space for people on the autism spectrum, in the hopes that we and others could learn from furries how to better support participation and inclusion for people on the autism spectrum in our own communities. We were also interested to know how the furry fandom and similar creative cultures might better support people on the autism spectrum in having the kinds of experiences they want to have at conventions and other social events. The project, “Social Connection through Creative Community: An Ethnographic Study of Autism in the Furry Fandom,” was funded by a Duquesne University Faculty Development Fund grant to Dr. Elizabeth Fein. Additional assistance with data analysis was provided by Amy Adelman.

Supporting information in this report was funded in part by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Data were collected through 9 focus groups (each of which had between 3 and 10 participants) and 11 individual interviews, conducted at Anthrocon as well as a variety of other large, small, and mid-sized furry conventions in the US and Canada. In order to comply with laws governing ethical conduct of research, all participants were over the age of 18. Any attendee over the age of 18 was welcome to participate in the groups, whether they identified as being a person on the autism spectrum, had friends or family members on the spectrum, or were interested in the topic for other reasons. Of the 78 total people who participated in the research, 37 reported having been diagnosed with an autism spectrum condition, 20 reported that they had never been formally diagnosed but thought they might be on the autism spectrum; 12 identified primarily as close family members of someone on the autism spectrum but not on the spectrum themselves, and 9 fell into none of the above categories.

The focus groups and interviews were organized around the following questions:

- Preliminary research suggests that the percentage of furries who identify as being on the autism spectrum is several times higher than the percentage of people diagnosed with autism in the general population. What do you think are some of the reasons for this?

- Are there things about the furry fandom that you think might be particularly appealing for people on the autism spectrum?

- Does autism affect your involvement in the furry fandom in any way? If so, how?

- Have you met many (other) people on the autism spectrum through the furry fandom?

- What are some of the things that make it difficult for people on the autism spectrum to participate in the furry fandom?

- What are some of the things that make it easier for people on the autism spectrum to participate in the furry fandom?

All interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions were analyzed thematically using the software program NVivo. A first review of the data was conducted by the research team to identify significant themes and patterns; the data was then reviewed again and coded according to those themes. Anonymous quotations from participants are used throughout this report to illustrate these themes. The quotations are in italics; quotations from participants have also been used for section titles. We have removed all identifying information from these quotations.

What motivates people on the autism spectrum to participate in the furry fandom?

- The inclusive, accepting nature of the fandom

- The content of the fandom

- Activities common in the fandom

- Creating and roleplaying a fursona

- Fursuiting

- The blend of online and in-person socializing

- Beneficial consequences of participation

Though percentages vary (depending on the study* and methodology) Furscience has documented anywhere from 3.7% to 15% of the furries in the fandom self-report a diagnosis and/or self-identify as a person on the autism spectrum. From our 2018 study:

All respondents were asked the question “Do you consider yourself on the autism spectrum?” Response categories were “no” (n = 927; 66.7%), “unsure” (n = 173; 12.5%), and “yes” (n = 182; 13.1%). A total of 107 respondents did not answer (7.7%), so were deleted from the dataset. This response pattern did not vary by age or sex.

Participants reported many reasons why the furry fandom might have such a high rate of participation by people on the autism spectrum. The reason most commonly observed was the inclusive, accepting nature of the fandom.

I think what makes the fandom so appealing is most often the inclusiveness we have. Doesn’t matter what gender, race, religion, even all species, we accept each other for who we are.

It’s difficult to be in a society where everyone thinks differently from you. And kinda in a different method of interpreting the world and understanding what’s around you. And what I see in the community here is that you can throw that all aside and however you wanna interpret the world or interact with becomes acceptable. So you don’t have to try to fit another way of thinking. So you can really just be yourself, basically.

Participants sometimes pointed out that many people in the furry community have had some experience of social exclusion or marginalization, and this often inspires furries to be accepting of others, including those whose social behavior comes across as unusual.

There’s so much respect for people that are not quote-unquote normal, because I think most people in this fandom, at some point or another have felt outcast, and they don’t want anyone else to feel that way.

People who are on the autism spectrum, [it] may be that more of them just relate to animals more than humans. Because I’ve personally felt that, where it’s like ‘oh, wow, look at that human, they act completely different from me’ but like look at a cat, now I see a lot of mannerisms in myself that I can see in a cat. I know how a cat speaks, but I don’t know how a human speaks. So, maybe there’s just a bunch of autistic people who identify more with other species than humans.

For some, being able to build a bridge between animals and humans, through sharing an interest in anthropomorphic animals, felt like a step in the direction of deeper human connections.

I understand the importance of being around people now; I didn’t understand it in the past. But being around animals – at one point I would [have been] perfectly fine with being, like, on an island, by myself, for the rest of my life, just around some wild animals. I thought that would be cool. It’s kinda relieving to be able to bring it one step towards people.

In addition, many participants pointed out the artistic, creative side of the fandom as a particular draw.

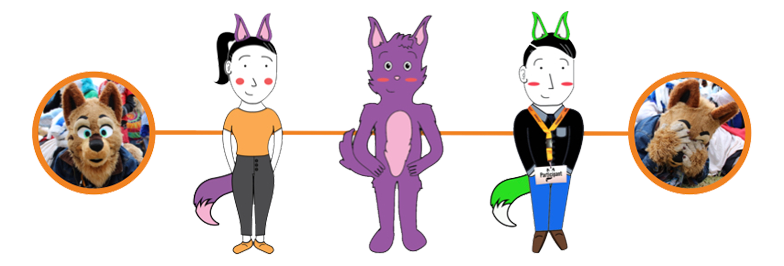

Original Artwork by: Anne Marie Brown

I know what made the fandom appealing to me, such as the diversity and the creativity that we have here.

A lot of those kids [on the autism spectrum] tend to have some sort of artistic, creative side, whether that’s musical, theatrical, drawing, painting. So I feel like those two things [creativity and animals], connected, make that connection to that furry fandom even stronger.

Many of the activities common in the fandom support social participation by people on the autism spectrum. Participants mentioned board games, karaoke, and fursuit dances as structured opportunities to engage in shared activities, try new things, and risk some embarrassment in a supportive environment.

I’ve never liked to dance. I hated to dance, and I never wanted to participate in anything like that. And coming to [convention] last year in suit I just decided: you know what? I don’t even have to be me. I can be something else for a moment. And I can go out to that dance and just pretend like I’m dancing. Pretend, you know, blend in with what everybody else is doing. And then, after I gave myself a chance to do that, it was like “Wow, this is why these people are enjoying this. I now like it too”. And I love to dance now, and I dance all the time. And I went to the rave two nights ago and had a blast.[…] I prefer to dance in my fursuit, but I’m capable and do enjoy doing so without my fursuit now.

In particular, many participants appreciated the opportunity to create and roleplay a fursona: a version of themselves as an anthropomorphic animal, often with traits they wished to develop in themselves. This gave them a chance to experiment safely with more outgoing, confident social styles despite often having had negative social experiences in the past.

When I was creating my character, um, I noticed that one of the main qualities I gave him—this was after some introspection—was confidence.[…] And I think that’s what a lot of us here do in the furry community is we create an image of ourselves that we want other people to see, that the average society might not necessarily see that. But, in the furry community, we take everything at face value, basically. We see a person and that’s who they say they are and we trust in that. And, even if it isn’t true at the moment, it eventually becomes a reality. And I think that’s what allows people on the autism spectrum to communicate within the community so easily compared to other aspects of society.

Cultivating a fursona provides an opportunity to practice new ways of reacting to difficult situations.

Sometimes when I’m feeling stressed or overstimulated, and having trouble dealing with that stress and being present in the moment, I think about my fursona and imagine what he would do, and use that as a way to get through a situation and process it differently. So I think that identifying with a fursona or animal alter ego is something that is, that can be, therapeutic for people on the autism spectrum.

Fursuits offer particular benefits to people on the autism spectrum. For those who have sensory sensitivities, fursuits can provide a buffer against sensory input, while also providing sensations of weight and pressure that some find calming.

If I was going to put a suit on, I would be a lot more social and willing to go up to people and hug people, ‘cause I don’t normally like to be touched, so, but if I’m in a suit, I’d be perfectly fine with that.

Metaphorically, too, the fursuit can buffer some of the sensitivity to social judgment experienced by many on the spectrum.

I take everything personally[…]Those sort of things don’t roll off my shoulders. Whereas I put my fursuit on, and it just goes whoosh! and it helps – it’s almost like it’s like a second skin sort of thing. It’s a harder kind of outer shell that takes the hit for me.

The simplicity and deliberateness of nonverbal communication among fursuiters, as well as the decreased pressure to communicate verbally, was a relief to many people on the spectrum who struggle with the speed and nuances of everyday verbal and nonverbal social communication.

Fursuiters tend – since they don’t have the expression in the face – they tend to be more gesture-based and physical. And I think that’s pretty appealing [for people on the spectrum] ‘cause you have to perform, where you can get by with the most basic emotion that’s easy to read, and there’s no ambiguity there.

The consistent positivity of fursuit expressions, and the consistently positive response they evoke from others, mitigated the pressure of constantly having to make eye contact, assess the facial expressions of others, and modulate one’s own facial expressions accordingly, which can be wearying and anxiety-provoking for people on the spectrum.

People who are on the spectrum, it’s very difficult for them to make eye contact with people. You know, it’s kind of one of my problems. […] But when you’re looking at a fursuit, and a mask, it’s only got one expression, and you don’t need to worry about, you know, what’s going on behind the mask. It’s always smiling. It’s always happy. It’s always charming and bright.[…]And when I put on a fursuit, at one of the conventions that I went to, everybody around me had a smile. They wanted to come up to me. They wanted to get pictures[…] That is a good confidence boost right there.

The way that the furry fandom blends online and in-person socializing was also frequently mentioned as helpful for people on the autism spectrum. Many people on the spectrum find it easier to socialize online, because it doesn’t require the same degree of nonverbal communication as face-to-face interactions do. The fact that the furry fandom takes place both online and in-person helps participants on the spectrum form social connections in that context, then continue these relationships in the sometimes more difficult, but also potentially rewarding, world of in-person interaction. Meanwhile, a commitment to making emotional nuance explicit, cultivated online out of necessity, is carried forward into in-person interactions within furry culture.

I would also like to point out that a huge, huge portion of the furry community is online. Like I know that we’re at the convention right now, but online is entirely text-based. You don’t have to worry about “Am I doing the right body language? Am I reading that body language right? What is that facial feature?” How you communicate only and entirely in text is a little different, and I find that it’s much easier to read that, and people have to be much more explicit or have like, ascii emoticons, or something to convey tone that is much more difficult to do on the fly in real life. And I feel like that kind of carries over when people in the furry fandom meet in real life.

Furries on the autism spectrum reported many beneficial consequences of their participation in the fandom. Many reported decreased social anxiety at furry events.

At furry conventions, I noticed that I have almost no social anxiety like I normally do.

Therefore, they are more likely to try new things and expand their social repertoire, building social skill and social connectedness in ways that may have been hard for them to do in other contexts.

When I first joined the [fandom], that would be one of the few times in my life where I have found people who are of like mind, of same mind who I could be more open with, unlike the bullies and the other students that were at my schools[…] I had very, very few friends during the schooling.

These experiences helped people grow and change over time in ways they appreciated.

That’s something great about this fandom that makes it so easy for people with autism to get into it. It’s very accepting, and, like, it’s chill with whoever you are and whatever you like. It’s like, “hey you’re awesome no matter what”. Looking back at my first con which was Anthrocon two thousand seventeen, I was very different. I was very timid, shy, I was not as confident in how I spoke[…] Being able to portray yourself as someone that you want to be and something you really admire, being able to turn yourself into that over time, it’s just, it’s something really positive about this fandom.

For some youth on the autism spectrum, the social support they received through the furry community had been literally life-saving.

Honest to God, without the support from the furry community, I probably would have offed myself a couple years ago. […]Pretty much if I didn’t stay home and play video games all day, I would have ended up dead in in a bathroom at school, cause it was that bad. I think without the support of the furry community, I probably would have. Even when you’re at that low, it’s nice knowing that people do care.

Many parents and family members of youth on the spectrum spoke of how happy they were to see their family member having these kinds of experiences and forming social connections with others. In our focus groups, they often became visibly tearful as they described watching their family member going off and having fun with like-minded peers.

You’re so connected to your child, you can see how emotional you are getting ‘cause you feel like you’re helping your son to find something to connect to, and, which he may not necessarily get at when he was growing up: finding friends, keeping friends, interacting, and being invited to things. There are things that parents kinda look for, ‘cause they want their child to be socialized and to have friends, and because we’re not gonna be here all the time, so I worry about what that future brings.

Participation in the furry fandom is clearly a deeply rewarding activity for many on the autism spectrum, providing the kind of opportunities for social connection, skill-building, increased self-confidence, and just a general good time that are often all too rare in their lives otherwise.

Barriers to participation and recommendations:

This section explores some of problems identified with conventions for people on the autism spectrum and some recommendations to mitigate and accommodate these concerns. We hope these recommendations will be useful. Even in this unusual time of COVID-19, we are available to help implement in any way we can.

Participants emphasized how accessible, welcoming, and potentially transformative the furry fandom can be; they also described factors that made it difficult to participate in the fandom in all the ways that they wanted to. So what can we do to make these opportunities more accessible? What stands in the way of participation, and what can we do to help?

In the next section of this report, we will discuss the barriers to participation that were reported by participants in our interviews and focus groups. For each of these barriers, we will also make one or more recommendations for addressing them. These recommendations emerged out of our interviews and focus groups. They are informed by our own expertise on the Furscience team; however, except where noted, they are all based on suggestions made and supported by our research participants. Depending on your local public health guidelines adapting to situations like COVID-19, some of these recommendations may require modification.

Problem: “It can be overwhelming.”

Recommendation: Quiet Room

Original Artwork by: Anne Marie Brown

In the crowded, hot, bright, exciting, and highly social environment of a con, it’s easy for someone on the spectrum to get overwhelmed. For many people on the spectrum, large crowds are difficult to navigate. This is both because of the intensity of social processing demands posed by big groups of people, and also because people on the spectrum may have problems shifting attention and with processing visual-spatial information, which makes it hard to chart a course through a fast-moving crowd to get to that panel or that booth in the Dealer’s Den.

What are some things that are difficult? Well, the fact that there are many people. It’s a crowd. Especially at the conventions. It can be overwhelming. But usually like when it happens, I just focus on one direction. If I see someone I know, it’s even better. For example, I know I have to go at the one panel. Well I just focus on it. I don’t look at people, just go at the panel. Enjoy the panel. And then I go in the one direction again.

Clear signage and clear pathways help – especially when others respect those guidelines.

The number one thing I wish people would do to better accommodate people with autism is stop loitering in the walkways, get off to one side. So that people who want to move around or go someplace else can move. That’s the easiest thing they could do, I think, to make this space friendlier.

Sensitivity to heat also poses a challenge for many people on the spectrum, especially those who fursuit.

It’s unbearably hot[…]that for me is quite a hard thing, ‘cause my heat tolerance isn’t the best.

Sometimes, getting overwhelmed happens fast, without a lot of warning. It can be hard to find a quiet place to go, and hard to explain why you need to.

You might be able to go out and then socialize! be nice! have fun! But when you’re done, you’re done. You can’t handle any more. And then people like to: “hey, why are you – what’s up?”, you know, like “you were just fine a minute ago”. And it’s like – it’s just too much. I can’t handle it anymore.

When overstimulated by sensory input and/or intense, ongoing social interaction, many people on the spectrum benefit from a quiet, low-stimulation environment to chill out and recharge. Both those on the spectrum and those who have close friends, partners, or family on the spectrum, often suggested a “quiet room” where participants could go when feeling overwhelmed. This was by far the most common suggestion we received for how to improve the experience of people on the spectrum at cons.

In the last con I went to which was in April, they installed this new thing, which was basically they just had a room and it was completely quiet. They had, like, soundproofing on the walls, and they had stereo headphones that you could put on, and you could put on music, or you could just sit there and color, and it was very peaceful, and you could even like, they had beanbags and stuff, and you could just take a nap. And it was really, really nice. So, that would be wonderful.

Participants suggested that the room should be advertised in the con booklet as being a quiet space, available for those who feel that they need a quiet space to recharge, and it should be used exclusively by those who need it for this purpose.

The room should be equipped with: comfy chairs and/or beanbag pillows; headphones and/or earplugs; quiet activities such as coloring; water, snacks, juice; small items to fidget with; tissue boxes; and possibly comforting stuffies.

In order to accommodate those with sensory sensitivities, the lights in the room should be dimmed, bright colors be avoided, and those using the room be asked to avoid using strong perfumes and scents.

Some suggested that the room could contain a few tent-like structures, so that those who needed to be all alone could be alone, and those who needed someone with them could be with that person in the main space.

In terms of location, the room should be located somewhere that is easy to find on a map, easily accessible from the main social spaces of the con, but not directly next to a room that was very noisy so that quiet could be maintained. It would be best if participants did not need to navigate elevators or escalators while trying to access this room.

People should be able to remain in the room for as long as they need to, without time limits.

It would be helpful to have staff members available to check on the room occasionally to make sure it remains clean and tidy, and clean things up if they’ve gotten disorganized. Those people should have some basic training in how to communicate effectively with people on the spectrum and those who are feeling overwhelmed or distressed, but should not be expected to take on a therapeutic role – their role is just to make sure the space remains available and accessible for those who need it.

Having a quiet room available will allow participants to continue enjoying the lively atmosphere of furcons while also knowing they have a place to go when it all gets to be a little much.

Problem: “Despite the tools that the furry fandom can give to deal with interacting with people, at the end of the day, you still have to interact with them. It can still be hard.”

Recommendation: Education for the Fandom about Autism and Related Conditions

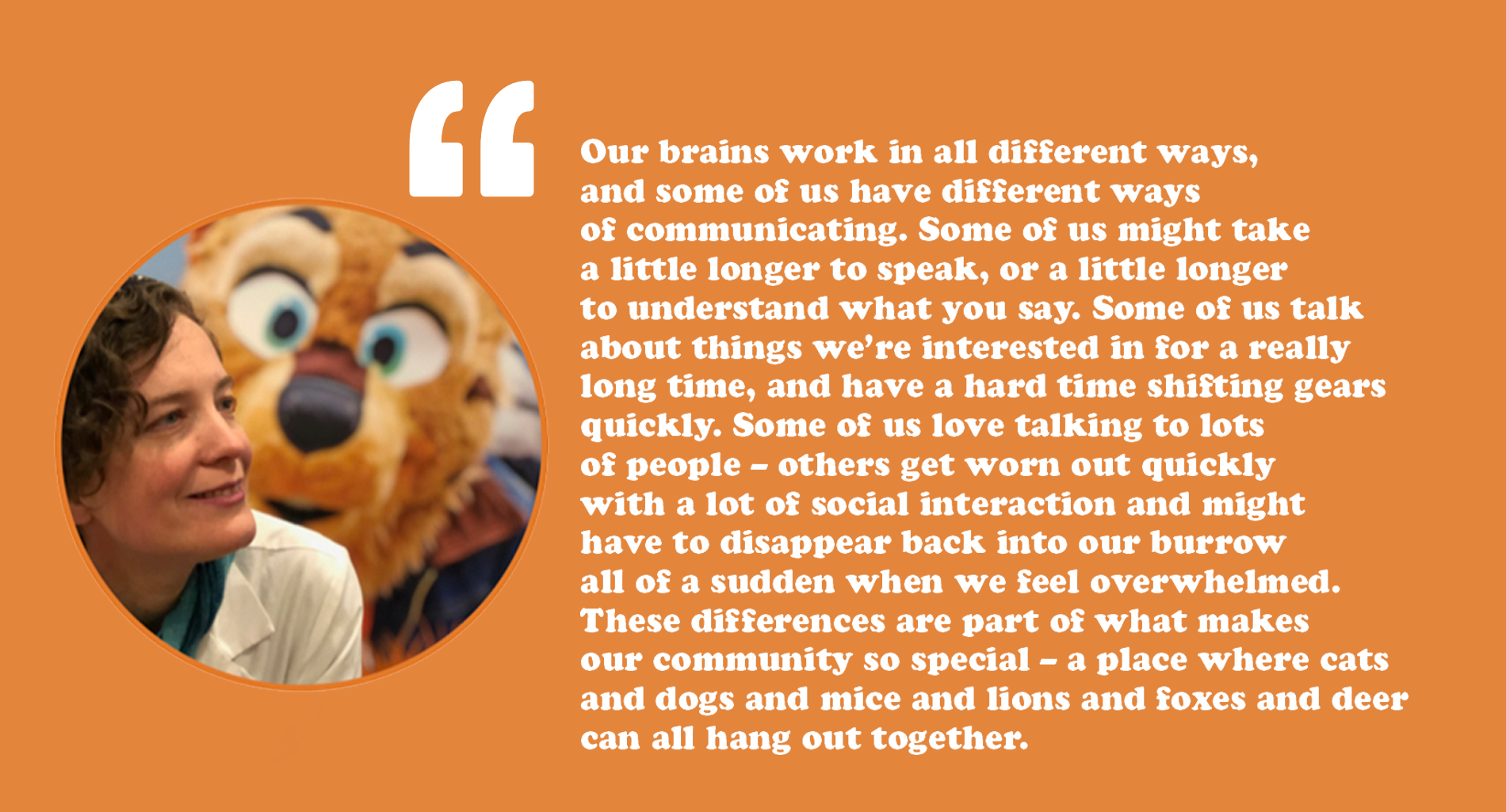

Many participants noted that, despite the ways in which the fandom helped them with their social problems, they still experienced consistent difficulty with communication: trouble understanding other people, trouble making themselves understood, and anxiety about how they would be interpreted by others. The challenges faced by people on the autism spectrum in social life are mitigated in the fandom, but they don’t completely go away.

One of the things that’s a little difficult is: a lot of what I’d struggled with is the body language of people— communicating with people and trying to read moods or how they use their body or their faces to portray how they feel. It’s kind of daunting.

Participants often reported feeling anxious that they would encounter negative judgment from others for their social communication blunders, even though they described the fandom overall as accepting and nonjudgmental.

I always worry, like, are people being turned off because I – am I geeking out? And I am I talking too much about this one thing? Am I talking too much? And so the self-consciousness—with any social interaction—it doesn’t disappear entirely.

However, once members of the community learn about these social communication challenges, they are often able and willing to be supportive.

The friends that I met early on in the community, they were a little apprehensive of me at first, because I spoke very literally—very very literally. […] And because of that, it made communicating a bit difficult, early on. But, I was very fortunate in that the people I met, though, once I told them like “hey – I don’t get this stuff sometimes, and if I misspeak just tell me”, I was so fortunate that their response to that was, “I will gladly work with you with whatever you need.”

When others are already familiar with the social communication challenges associated with autism, it makes it easier for people on the spectrum to navigate social misunderstandings.

Sometimes I don’t always understand what other people mean, but after that I just say, “I’m Asperger, I have a problem understanding. Can you be more clear?” So usually they understand.

While the social communication challenges that come with autism as well as other conditions (such as ADHD, dyslexia, auditory processing disabilities and speech impediments) don’t go away, they become less of a problem when others are familiar with these challenges and have signaled that they are willing to help.

Participants suggested it would be helpful to hold a panel where participants could learn more about autism and related conditions from an accepting, nonjudgmental standpoint. In particular, when asked what they wished others in the fandom knew about their condition, participants on the autism spectrum said they wished others understood that:

- Some people have a hard time understanding rhetorical questions and sarcasm, and tend to take things literally.

- Some people have a hard time recognizing and remembering faces (even if they can recognize and remember fursuits!).

- Sometimes social conflicts arise due to people misunderstanding each other’s social cues, rather than because of genuine disagreements or bad intentions.

- When someone needs to leave a social situation quickly, it might be because they have become rapidly overwhelmed by external stimuli they can no longer effectively process.

- Just because someone was able to handle a situation effectively and comfortably in the past (even the very recent past), it doesn’t mean that they can do so right now. Their internal and external circumstances may have changed in significant ways, and those changes may not be obvious to those around them.

- People’s experiences of time differ. While one person might be able to focus on the present moment, another may need to plan for the future in order to feel safe and secure.

- People’s thought patterns and thought processes differ, so what might be useful advice for one person might not be a useful coping strategy for another.

Some participants also mentioned that it might be helpful for con security to have some basic training in how to interact effectively with a person on the autism spectrum who is in distress.

Recommendation: Celebrate Neurodiversity Ribbon

A number of participants, both those on the spectrum and parents of youth on the spectrum, mentioned that it would be helpful to have a way to identifying others who are familiar with autism, and who are willing to be supportive of the social and communication differences that can arise due to autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions.

I would love it if there were some form of identifier for people who were autism friendly[…]That would identify for me, as a parent [of a person on the autism spectrum], saying, “Oh this person understands, this communication is going to be a little bit of a challenge.” It occurred to me when you’re talking about artists, they might not understand where we’re coming from, when we’re being real particular about something [when arranging a commission]. I would be more apt to even talk to an artist if I saw some identifier saying, “I get it,” even if they’re not on the spectrum themselves. So some sort of identifier. I don’t know how you guys feel about that but as a parent that would help me out.

The term “neurodiversity” (when talking about a group, or “neurodivergent” when talking about an individual) is often used to describe the ways that people’s brains are different in a way that recognizes and appreciates difference without pathologizing it.

For some people, like for me, I have trouble articulating quickly that I have problems with communication, so I think having a ribbon that just said “neurodivergent” is kind of like having a button that says, “Ask me about this…” So to me, that would be helpful. I know that’s going to apply to everyone because not everyone wants to share that. But then you don’t have to take a ribbon if you don’t feel comfortable with it.

In several of the focus groups, participants discussed whether it would be better to have a ribbon specifically for people who identify as neurodivergent and another for people who are “neurodiversity friendly,” or whether it would make more sense to have an image that functions like a Pride flag (used by both people who are LBGTQ and those supportive of LGBTQ people, without specifying which one you are). The consensus overall was that it would be best to have a ribbon that indicates the person is familiar with neurodiversity in some way, without suggesting people disclose whether or not they identify as “neurodivergent” themselves.

Our recommendation is that cons consider offering a ribbon that reflects this voluntary self-identification.

Instead of just a circle, perhaps a circular Möbius strip (a common symbol for neurodiversity), drawn with interlinked rainbows or animal tails with the phrase “Celebrate Neurodiversity.” NB (1) Images of puzzle pieces are controversial in the autism community and should be avoided.

The con program and informational flyers could then explain the ribbon by saying something like:

If someone’s wearing a “Celebrate Neurodiversity!” ribbon, it means they know and appreciate that different brains work in lots of different ways. If you’re curious about how someone decided to wear a Celebrate Neurodiversity ribbon, try saying “I like your ribbon!” and maybe they’ll tell you more about why they’re wearing it.

A number of participants mentioned that the furry community is already in the habit of supporting those with physical, perceptual, and communication differences – because of the community’s commitment to inclusiveness, but also because they are so used to accommodating fursuiters! Providing more education to the fandom about the ways people’s brains, bodies, and communication styles differ, and providing a way for people to signal that they understand and are willing to help, will help people on the autism spectrum know when they can count on that support.

Problem: “I don’t know how to properly interact with all these people because I literally don’t hardly know any of them”

Many participants on the autism spectrum reported that they have difficulty knowing how get started with big-group socializing: to initiate conversations with strangers and enter into group conversations:

It’s kinda hard because I don’t really know when to step in or when to make an interaction, something like that. It’s really hard for me because I, well, I do have autism, and I don’t know how to properly interact with all these people because I literally don’t hardly know any of them.

When does it work well for you?

Well when I know somebody, I guess. I can easily walk over to them and say, “Hey I know you from this place” or something like that.

And what makes it harder?

When I don’t really know them because, well, they have a lot of other friends, and they don’t really have time for somebody like me who they don’t know.

As a result, they often felt lost on the fringes.

I’ve just never been very social to begin with, and it can be hard for me to be the first one to start talking, or, you know, to speak up[…]Never quite sure what to say, unless, you know, someone like asks me a question, or we’re already part way down some sort of conversational path, and I, you know, have a point to make.[…]Large groups have always made me nervous.

Sometimes, this may be due to the misperception that everybody else knows each other and is comfortable with each other already.

You’d be surprised at how many people are like: “I’m just feeling shy because everyone else knows each other and I don’t really know how to come in” and I’m like, all you need is someone to go, “hey, come here. You can sit with us.” And that’s what I try to do. […]’Cause that’s how I came in. I was scared. I didn’t know where to come from. At my first meet, this little teeny meet. And I was terrified because I knew the person who took me there to go with ’cause I wanted to at least have someone I knew, but I literally – I went up and I was like “I gotta get some courage,” and I talked to this one girl. Who happened to be my best friend now for four years.

Having at least one good friend available to make introductions makes a tremendous positive difference in breaking the ice.

When I first joined, I was kind of nervous to know anyone. And what actually helped me get into that was actually getting to meet a few people and actually them encouraging me to go out and have fun, and it turned out to be a really fun time.

Interactions with single individuals are often easier than large group conversations.

I have some challenges too, such as being with big groups. So, I try to interact with a single individual at a time, in order to feel that I have the interaction that I need in order to bond a friendship.

And once that first connection is made, interaction tends to gets easier.

It’s hard to, like, talk first, but once you do it gets easier. And then, like I said, it just spirals. It’s like I get more confidence and then I can start talking to more people, and it feels comfortable doing that.

Recommendation: Small group events targeted toward people on the autism spectrum and those with other social communication differences, allowing them to connect and get to know each other through one-on-one conversation and structured activities.

In order to help people who struggle to make a first connection in large groups, we recommend that the con offer a “NeurodiFURsity Meet-and-Greet” where people dealing with social communication challenges can connect with each other in a smaller group.

Original Artwork by: Anne Marie Brown

I think it might be helpful to have opportunities or sessions that people can go to that were smaller in number, that would help folks on the spectrum to feel a little bit easier or without hesitation. Because it’s not easy, still.

The event should feature structured opportunities to talk with one other person; some participants suggested something like a “flash dating” format where you are paired at random with other attendees for a time-limited conversation, perhaps while choosing from a list of conversation topics. (Some of our participants mentioned that our focus groups were helpful for them in this way: an opportunity for structured conversation in a small, quiet group).

If there were a session here that was written up, and it mentions that it’s a session for folks on the spectrum to have an opportunity to meet people – but in this group session, it would be a one-on-one opportunity for a few minutes here and there in a more calm area, quiet area.

Events like this would allow for people on the spectrum to connect with each other and potentially to strategize together and share experiences and recommendations they’ve learned through their own experience, while also potentially creating a greater sense of belonging.

I think part of it’s like, if you realize you’re not alone, it helps you. ‘Cause sometimes you think ‘oh it’s just me, I’m the only one who’s like freaking out, I’m the only one having problems’ and you just build up this entire situation, so it’s like you do like a meet-and-greet, see these other people like you, it’s sometimes then easier.

For this reason, we recommend that opportunities be made available specifically for people who identify as neurodivergent to meet and socialize with each other. (Also, the word “neurodifursity” is just too good not to take advantage of). However, any kind of small-group, structured opportunity for people to interact one-on-one, without the pressure of having to start a conversation spontaneously, would help those who struggle to make that first connection. We recommend that this event be scheduled early on in the programming, so that participants can benefit from the connections they make through the remainder of the event.

Recommendation: Volunteer guides

Original Artwork by: Anne Marie Brown

Another recommendation is to create a list of volunteers who are available to hang out with shy newcomers and show them around. This resource does not have to be limited to people with autism or other social communication challenges – it could be for anyone coming to a con for the first time who doesn’t want to be entirely on their own and could use a guide dog/cat/fish/etc.

During my first convention I was drowning, and I met up with someone during a writing panel who offered to just escort me around. And that, just having someone there who I could just rely on, I could just talk to them, that really helped me, so I didn’t have to focus on everything around me.

Having someone who can sort of guide you around can be a huge help.

There was a lot of discussion within the groups about how to set up such a listing, where to host it, how people could join it, et cetera, but no clear consensus about best practices, other than a sense that it might be similar to how people volunteer themselves as fursuit handlers. The mechanics of how to handle this effectively will probably differ from event to event. The important thing is that anyone who is coming to a con and feeling shy about meeting new people can have at least one person there who they know will buddy up with them, introduce them to others, and be a friendly face in the crowd.

Recommendation: Friendly Bench

One recommendation (that was made to a team member outside of the research context) that we liked a lot was to designate a bench or other such spot where attendees could sit if they would like others to strike up conversations with them. As opposed to informal hangout spaces such as the “Zoo”, where people go for a variety of reasons, the Friendly Bench is explicitly marked as a place to sit if you’d like to chat with people, even people you don’t know yet. This removes ambiguity from social interaction and encourages people to feel more confident starting conversations with strangers and less worried about whether this will be welcomed. Meanwhile, those who would like to look after fellow furries who are feeling a little lost could keep an eye out to see if anyone is sitting on the bench alone.

Problem: “I’ve been trying to go since I turned 18….Budgetary and financial reasons blocked me.”

A number of participants reported that financial factors kept them from participating in the fandom in all the ways that they wanted to.

If you’re not well off, and you don’t make a lot of money, it’s just hard and it’s stressful.

People on the autism spectrum often have difficulty finding and keeping employment, and so financial hardship is more common in this group. The cost of fursuits, the cost of convention registration/hotel/travel, and the difficulty getting time off of work were mentioned most frequently. Parents of youth on the spectrum, in particular, often reported feeling torn between alarm at the cost of fursuits and appreciation for the social benefits they provide.

I helped her buy her first [fursuit head]. I think it was nine hundred U.S. dollars – and I was gob-smacked. And I said, “Oh my god. Nine hundred.” […]Her dad was a bit deterred at the price, but I said, “It’s her money. Let her buy what she wants.” […]She’s very introverted, very quiet, but when she puts her mask on, her costume on, she becomes very exuberant, and she’ll pose for pictures, and you know I never see her do that in her life. And so I think, for her—and for me—it’s great to see her show different emotions.

Recommendation: Explore funding/discount opportunities for people on the spectrum

This was one of the issues where few clear solutions emerged from our discussions. As a research team, we wondered whether there might be opportunities to create or find financial support for people on the autism spectrum who wanted to attend cons or purchase a fursuit but were having difficulty doing so due to lack of financial resources. One challenge to a formal discount or scholarship program is that many people affected by autism or similar social communication challenges do not have a formal autism diagnosis; this is especially likely to be the case among those who are not financially well-resourced. Another challenge is that discount programs targeted toward one group risk giving the appearance of inequity towards other groups who might also benefit from such support (for example, furries who are from groups that are marginalized in other ways). And while furries are legendary fundraisers, these efforts are traditionally targeted towards animal welfare organizations.

One option is to address this issue through informal collaborations: for example, between a fursuit maker who is willing to offer work at reduced cost to people on the autism spectrum and networks of therapists/clinicians who work with people on the autism spectrum. Another option might be to create a scholarship fund for people on the spectrum to receive assistance toward the cost of travel/registration. As the benefits of the furry community and of fursuiting for people on the spectrum become more widely known, those outside of the community may become more willing to financially support it.

Lastly, it is important to note, as many participants did, that purchasing an expensive fursuit or even attending a large national convention isn’t necessary to be a part of the fandom. The continued proliferation of local events, the openness of the community to less elaborate forms of fursuiting, and the willingness of many members of the community to let friends try their suits all help make these opportunities more available to a wider range of people.

Problem: “To me, this is very strange.”

Parents and other family members of youth on the autism spectrum occupy a unique position in the fandom. They are often learning about a new and unfamiliar culture, and may feel uncertain about whether to support their family member’s participation in that culture – and about how to support it, especially if they are accustomed to doing so from a place of fluency and adeptness with social norms rather than as a cultural novice in a world more familiar to their family member than themselves. And they are the ones who will be around to help youth on the spectrum try to build bridges between their experience in the fandom and other aspects of their everyday lives.

Family members of people on the spectrum who participated in focus groups and interviews often reported an initial sense of confusion or even unease about the fandom. However, once they got to know the fandom, they were often more comfortable with their family member’s participation.

To me, this is very strange. That’s why I came to see what it was about, why my son was so involved in it. But it makes more sense now to me. You know, the way he sees things, that’s what I’m seeing now! Okay, I don’t understand: why is this person dressed like this? Why does this person act like that? ‘Cause that’s not the way that I would interpret things. But he’s very comfortable with it, and he’s comfortable here. I think a lot of [the attention] needs to go to education, to people like me.

However, parents still sometimes wonder how to help their child stay safe in what is in many ways an unfamiliar culture, especially given the centrality of the Internet.

Can I ask a question? One of the things that that I really worried about, is like you were saying, you chat online with your friends – my [family member] doesn’t have friends who he physically interacts with unless he’s here. It’s all online. And I worry all the time that there are gonna be people who take advantage of him. Can somebody talk to me about that, whether that’s a legitimate concern?

They struggled with how they could continue the learning process that they and their family members were both having at furry events once they return home.

You don’t know how much I wish there was a group like this near where we live where I could come and talk to people to figure out: […]What am I doing that’s helpful? What am I doing that’s not helpful? I really wish there was some place I can go to talk with people!

Recommendation: Consider informational get-togethers for local parents throughout the year

This was another area where our group discussions did not produce a lot of clear answers. However, our research team had some thoughts. Anthrocon and other furry conventions are already offering welcoming and informative events for parents who are accompanying their child to a con, but these events take place only infrequently. Get-togethers during the year for parents whose children are interested in the furry fandom, and who want to learn more about it, might be helpful – and might be especially so for parents and family members of those who are dealing with autism or who are neurodivergent in other ways. An annual “Neurodiversity in the Furry Fandom” meetup in Pittsburgh or other major con-hosting cities, sometime prior to the convention itself, would allow parents to learn more about the event their child hopes to attend, help the family prepare, and perhaps help them make new friendships that could continue into the con itself. This type of meeting could easily also be offered virtually via videoconferencing software such as Zoom or a free open source option such as Jitsi Meet.

Problem: “The hard thing is, she can’t tell anyone about it.”

One related concern, frequently raised by parents and family members of people on the spectrum, is stigma against the furry fandom amongst the general population. They wondered if this was making it harder for their family members to build upon the social gains and social support they find within the fandom and connect it to the rest of their lives.

The hard thing is: she can’t really tell anyone about it. And she makes these, you know, great costumes, and I’m always wanting to show my friends. You know, “Look at these amazing things she made!” And my one friend is totally fine with it. But anybody else would kinda be like, you know, “What are you doing? Why are you encouraging this kinda thing?” So I don’t think so.

I think the hardest is, and I noticed this with his school when he started coming up: that his peers were kinda at first mocking, you know, “Oh man, I can’t believe you’re doing that.”

Recommendation: Continued efforts to correct misperceptions and raise awareness about the fandom

As anyone reading this report likely knows, stigma against furries among people who are familiar only with stereotypes and jokes about the fandom continue to make it difficult for participants to integrate their experiences in the fandom with the rest of their daily lives. However, the tide appears to be turning, with recent positive coverage of the fandom in outlets like CNN,

@lisaling @cnn Congratulations to you, Heidi, and your team for capturing a heartwarming story of the #furryfandom on #ThisIsLife tonight! Thanks for the IARP/FurScience shoutout, too. We have the data but it’s wonderful to see it captured and shared accurately! pic.twitter.com/q7unPq7RYL

— Furscience! (@furscience) November 19, 2018

Rolling Stone, and Vice Media, participation in the fandom from an increasingly large and diverse group of people, and increasingly realistic portrayals of the fandom showing up in a variety of contexts.

Thanks so much for covering the furry community as they are—loving and kind and hopeful. Glad you see what we’ve been studying for years. Thanks for sharing it with the world. Stay well❤️ @FullFrontalSamB @amy_hoggart https://t.co/xnisPpVBwD #positivefurrymedia #sharefurscience

— Furscience! (@furscience) March 26, 2020

We all need to continue our efforts in this direction. It is our hope that reporting the results of this research in academic journals geared towards professionals in the autism field, as well as in more public venues (such as NPR affiliate WESA’s piece at Anthrocon, Pittsburgh) will also help to raise awareness of the potential benefits of the fandom – both within and beyond the community of people affected by autism.

CONCLUSION

We hope that this report and these recommendations will be helpful. We are available to answer any questions and continue in consultation, and we hope to help out in any way we can with putting in motion any of the recommendations that convention organizers would like to implement. It has been an inspiration for all of us on the team to work with the thoughtful, caring, and creative furries who have attended our groups and agreed to be interviewed, and though we cannot acknowledge them by name, we are grateful to everyone who took valuable time at their con to speak with us. We hope, as well, that these recommendations and material that we publish elsewhere will allow other communities to learn from the care and wisdom of the furry community.

For more information check out Dr Elizabeth Fein and her new book, “Living on the Spectrum” published by NYU Press:

You can also check out the Furscience Team’s new book, “A Decade of Psychological Research on the Furry Fandom,” where Dr Fein has an entire chapter on Neurodiversity in the Fandom. This book is available for FREE to download, or you can get your very own hard copy from Amazon.

For more on Furries and Autism in the media, check out Sarah Boden’s piece for Pittsburgh’s NPR New Station 90.5 WESA here, and be sure to watch Duquesne University’s video, featuring Dr Fein:

Thank you for sharing your world with us.

You can submit your questions or comments below, or you can reach out to Dr Fein directly.

I’m a therian, but I have autism. By the way, my wolf name is ShadowWolf.

I am an autistic furry and I wear it proudly. I am also a YouTuber.

Unfortunately, furry is still considered a children’s game.

This is not true.

It is a community that is mainly made up of older youth and adults.

My daughter’s autistic psychiatrist suggested therapy based on furry group meetings.

They work much better than regular meetings.

In costume, she is a completely different person.

She is not afraid to talk to other children and has fun.

Even without fursuit you can see progress.

She liked it a lot and decided to join the furry fandom.

The price of the fursuit is huge, but with the help of the foundation, we managed to raise the money to buy the fursuit.